On October 10, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell more than 800 points, its largest drop since February. The percentage declines were larger for the S&P 500 —with all 11 sectors lower—and Nasdaq, suffering its worst day in more than two years. Leading the way down were the technology shares that have fueled this year’s U.S. rally - though as the day went on losses spread well beyond tech. It was the beginning of a two-week period characterized by strong volatility on the markets, that reached its low on October 24, before US stocks staged a solid rebound as forecast-beating earnings reports from Microsoft, Ford and Twitter provided a more encouraging backdrop.

Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI). Source: Yahoo Finance.

What is behind the global stock market sell-off?

There was no single catalyst for the equity market drawdown but the correction on October 10 - as well as the following ones - was likely driven by several factors.

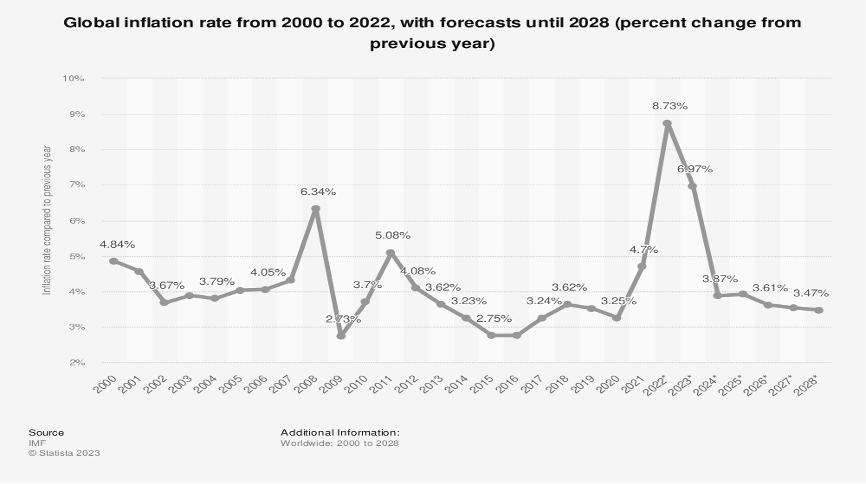

There is no doubt that rising bond yields were one of the key drivers behind the downbeat sentiment toward equity markets that led to the sell-off. Indeed, even though rising economic optimism caused the previous week’s bond rout, equities were unnerved by the severity of the reaction in fixed income – the 10-year Treasury yield raced to a seven-year high of 3.25% - and by the speed at which the nominal yield reached this level (as higher interest rates typically bring on tighter financial conditions which could dampen growth going forward). This repricing was exacerbated by hawkish commentary from Federal Reserve officials, with Powell noting that interest rates may be raised “beyond whatever the estimate of this rate is”. It is also noteworthy the rise in the real yield - exceeding 1% for the first time since 2011 – since it reflects expectations for higher inflation ahead, another factor that may put even more pressure on equities.

While rising yields might have set the stage for the sell-off, other factors should be taken into account for explaining the brutality of the drop.

A significant role was played by short-volatility bets. Data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission indicates that investors were shorting Vix futures – derivatives contract used to bet on stock markets remaining tranquil - to the greatest degree since January. When the US market sell-off made volatility jump, investors, trying to cover their positions, caused volatility to reach an even higher level. As a consequence, the VIX curve has inverted, implying the near-term outlook for equities is considered to be more uncertain than the longer-term. Despite that, this move was not of the same magnitude of what we experienced in February – also because, of the two VIX ETNs that fueled February’s “Volmageddon”, only one is alive and it is much smaller than it used to be.

There was no single catalyst for the equity market drawdown but the correction on October 10 - as well as the following ones - was likely driven by several factors.

There is no doubt that rising bond yields were one of the key drivers behind the downbeat sentiment toward equity markets that led to the sell-off. Indeed, even though rising economic optimism caused the previous week’s bond rout, equities were unnerved by the severity of the reaction in fixed income – the 10-year Treasury yield raced to a seven-year high of 3.25% - and by the speed at which the nominal yield reached this level (as higher interest rates typically bring on tighter financial conditions which could dampen growth going forward). This repricing was exacerbated by hawkish commentary from Federal Reserve officials, with Powell noting that interest rates may be raised “beyond whatever the estimate of this rate is”. It is also noteworthy the rise in the real yield - exceeding 1% for the first time since 2011 – since it reflects expectations for higher inflation ahead, another factor that may put even more pressure on equities.

While rising yields might have set the stage for the sell-off, other factors should be taken into account for explaining the brutality of the drop.

A significant role was played by short-volatility bets. Data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission indicates that investors were shorting Vix futures – derivatives contract used to bet on stock markets remaining tranquil - to the greatest degree since January. When the US market sell-off made volatility jump, investors, trying to cover their positions, caused volatility to reach an even higher level. As a consequence, the VIX curve has inverted, implying the near-term outlook for equities is considered to be more uncertain than the longer-term. Despite that, this move was not of the same magnitude of what we experienced in February – also because, of the two VIX ETNs that fueled February’s “Volmageddon”, only one is alive and it is much smaller than it used to be.

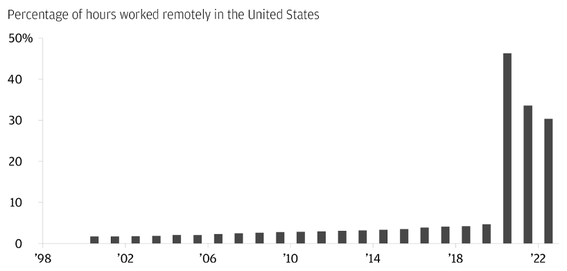

In addition, the drop in the tech shares was the result of the investor rotation between growth and value stocks. While fast-growing technology stocks have been the go-to investment in recent years – because of small economic growth - with the US economy now getting stronger, value stocks, that will benefit from the uplift, are more appealing to investors. The rotation is also encouraged by the fact that, given the lack of dividends and higher valuations, many tech stocks are arguably the longest-duration asset in the world and are, consequently, more exposed to raising rates.

Another point we need to take into consideration is that, while US economy has been growing at an incredible pace this year, the rest of the world has slowed. European growth is slowing down, due to a less favorable external environment and softer economic sentiment, and faces political challenges stemming mainly from Italy, and commodity-importing EM economies face headwinds from higher oil prices. Growth in China has slowed and is set to slow further, though this is somewhat offset by policymaker support. So, while for much of 2018 US equity market strength has been unaffected by moderating growth in other economies, the correction of October 10 may see this US equity market exceptionalism pause. Furthermore, the trade war is bringing more uncertainty on the markets because of its potential impacts on commodities, currencies and companies and, in general, on economic growth.

Finally, part of the sell-off was driven by systematic computer-powered investment strategies. As pointed out by Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon, "when you look at last week, some of the selling is the result of programmatic selling because as volatility goes up, some of these algorithms force people to sell" and so ended up exaggerating the rout. Risk parity funds, commodity trading advisers and “variable annuity” insurance accounts with a fixed volatility target – the three main types – have approximately $1tn of assets under management.

Another point we need to take into consideration is that, while US economy has been growing at an incredible pace this year, the rest of the world has slowed. European growth is slowing down, due to a less favorable external environment and softer economic sentiment, and faces political challenges stemming mainly from Italy, and commodity-importing EM economies face headwinds from higher oil prices. Growth in China has slowed and is set to slow further, though this is somewhat offset by policymaker support. So, while for much of 2018 US equity market strength has been unaffected by moderating growth in other economies, the correction of October 10 may see this US equity market exceptionalism pause. Furthermore, the trade war is bringing more uncertainty on the markets because of its potential impacts on commodities, currencies and companies and, in general, on economic growth.

Finally, part of the sell-off was driven by systematic computer-powered investment strategies. As pointed out by Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon, "when you look at last week, some of the selling is the result of programmatic selling because as volatility goes up, some of these algorithms force people to sell" and so ended up exaggerating the rout. Risk parity funds, commodity trading advisers and “variable annuity” insurance accounts with a fixed volatility target – the three main types – have approximately $1tn of assets under management.

Why can it be good news?

Behind the market turmoil there may be potentially good news. Indeed, bond yields are a reliable gauge of where investor think growth and inflation are going. In that sense, the run-up in long-term interest rates - which was at the basis of the stock market sell-off - is good news. Since both growth and inflation proved to be growing steadily, the Federal Reserve (but also investors) believe that interest rates need to return to more normal levels. So, the stock market sell-off is likely to be just a temporary bout of indigestion. In this respect, we also need to bear in mind that, even if rates are growing, they are far below historic definition of normal, considering that US economy grew by 3% over the past year and inflation has returned to 2%.

Furthermore, US economic fundamentals remain robust: strong job creation and better wage growth is supporting household incomes and consumption, while the fiscal stimulus from tax cuts is accentuated by higher spending. All of which is encouraging business investment.

Low unemployment may not result in strong inflation because of labor’s weakened bargaining power. Both the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve have sharply reduced their estimates of the natural unemployment rate and argue that labor markets have arrived at a “new postcrisis equilibrium, with more job creation and less wage growth.”

At the same time, we can not ignore that the market drop might contain warning signs for an expansion in its final stage. In its semiannual outlook, the International Monetary Fund said that the fiscal stimulus backed by Trump administration, added at a time when the economy was already growing, could lead to “an inflation surprise” and eventually hurting economic growth. It is also remarkable that JPMorgan claimed that, according to its model, the U.S. economy has a greater than 50-50 chance of tipping into a recession in the next two years.

In conclusion, even though the odds of a recession on the horizon are increasing, US economy is likely to keep running, at least in the short term.

Pietro Maraldi

Behind the market turmoil there may be potentially good news. Indeed, bond yields are a reliable gauge of where investor think growth and inflation are going. In that sense, the run-up in long-term interest rates - which was at the basis of the stock market sell-off - is good news. Since both growth and inflation proved to be growing steadily, the Federal Reserve (but also investors) believe that interest rates need to return to more normal levels. So, the stock market sell-off is likely to be just a temporary bout of indigestion. In this respect, we also need to bear in mind that, even if rates are growing, they are far below historic definition of normal, considering that US economy grew by 3% over the past year and inflation has returned to 2%.

Furthermore, US economic fundamentals remain robust: strong job creation and better wage growth is supporting household incomes and consumption, while the fiscal stimulus from tax cuts is accentuated by higher spending. All of which is encouraging business investment.

Low unemployment may not result in strong inflation because of labor’s weakened bargaining power. Both the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve have sharply reduced their estimates of the natural unemployment rate and argue that labor markets have arrived at a “new postcrisis equilibrium, with more job creation and less wage growth.”

At the same time, we can not ignore that the market drop might contain warning signs for an expansion in its final stage. In its semiannual outlook, the International Monetary Fund said that the fiscal stimulus backed by Trump administration, added at a time when the economy was already growing, could lead to “an inflation surprise” and eventually hurting economic growth. It is also remarkable that JPMorgan claimed that, according to its model, the U.S. economy has a greater than 50-50 chance of tipping into a recession in the next two years.

In conclusion, even though the odds of a recession on the horizon are increasing, US economy is likely to keep running, at least in the short term.

Pietro Maraldi