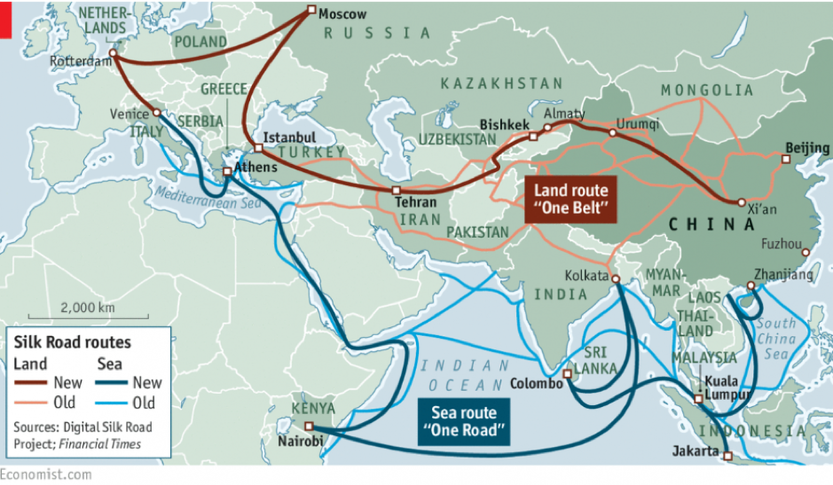

The Silk Road was an ancient network of routes that linked the East with the West, the Roman Empire with the Han Dynasty, the Ottomans with the Hindu. For centuries, it has been the main route for the trade of spices and fabrics before the circumnavigation of Africa and the establishment of sea routes. Trading along the Silk Road was perilous, dangerous, unsafe, time-taking and expensive and merchants had to hire armed guards to escort their caravans, but for the lucky ones who successfully completed the trip the reward was huge. However, we are not here to recall elementary school classes: what might surprise you is that the Chinese Government has decided to revival of this route in modern style.

The Belt and Road Initiative (also known as One Belt One Road - OBOR) is the largest infrastructural project of modern history. For those of you who cannot digest a statement without numbers, here are some to crack: this project is expected to cost $8trillion to fully implement. Once completed, the OBOR will cover more that 68 countries, including 65% (4.4 billion) of the world’s population and 40% of the global gross domestic product. If you have never heard of it before, do not be too surprised: Asiatic media are fond of speaking of this initiative but for their Western counterparts is not so common. So, what is the OBOR? No one is totally sure.

Technically speaking, the OBOR is a collection of interlinking trade deals and infrastructure projects across Eurasia. It is mean to address the “infrastructure gap” in and accelerate economic growth across Asia Pacific and Easter Europe. This is, of course, true: the Asian continent has seen a later development of industry and is still lacking many of those infrastructures, like highways, railways and ports, that elsewhere are taken for granted. The improvement of transportations and serviced will probably boost trades and production, attracting more companies in places that are now inaccessible. However, one question come naturally into mind: who is going to pay for all of this? China, the creator and promoter of the initiative, has pledged around $500bn worth in investments every year for ten years, a sum that will cover not only the cost of the projects in its mainland but also much of the cost of the projects in the 68 foreign countries. This means that most of the beneficiaries of the OBOR will have to finance with debt the project in their territories, debt that will be mainly provided by China. And here comes the pain.

The Belt and Road Initiative (also known as One Belt One Road - OBOR) is the largest infrastructural project of modern history. For those of you who cannot digest a statement without numbers, here are some to crack: this project is expected to cost $8trillion to fully implement. Once completed, the OBOR will cover more that 68 countries, including 65% (4.4 billion) of the world’s population and 40% of the global gross domestic product. If you have never heard of it before, do not be too surprised: Asiatic media are fond of speaking of this initiative but for their Western counterparts is not so common. So, what is the OBOR? No one is totally sure.

Technically speaking, the OBOR is a collection of interlinking trade deals and infrastructure projects across Eurasia. It is mean to address the “infrastructure gap” in and accelerate economic growth across Asia Pacific and Easter Europe. This is, of course, true: the Asian continent has seen a later development of industry and is still lacking many of those infrastructures, like highways, railways and ports, that elsewhere are taken for granted. The improvement of transportations and serviced will probably boost trades and production, attracting more companies in places that are now inaccessible. However, one question come naturally into mind: who is going to pay for all of this? China, the creator and promoter of the initiative, has pledged around $500bn worth in investments every year for ten years, a sum that will cover not only the cost of the projects in its mainland but also much of the cost of the projects in the 68 foreign countries. This means that most of the beneficiaries of the OBOR will have to finance with debt the project in their territories, debt that will be mainly provided by China. And here comes the pain.

The Chinese President Xi Jinping, the father and main promoter of the OBOR, has always described the initiative with words like ‘freedom’, ‘opportunity’ and ‘growth’. However, as the project goings on, the concerns about OBOR rise. The first question to ask is: what has pushed the Chinese Government to start this (highly) risky project? Why not to use these investments to improve domestic conditions? After all, we are all aware of the pollution issues or lack of welfare in China. An answer could be the following: as its runaway economic growth has slowed down, China has suffered from widespread overcapacity in heavy industries such as steel, cement and aluminum. A way of dealing with a declining domestic demand is expanding demand overseas and we do not need a PhD to imagine how much steel, cement and aluminum a project like OBOR will demand. The OBOR will not only absorb the overcapacity of China, but will also boost a decreasing economic growth, one of the main factors that contribute to the power and hold of the Chinese Communist Party. A second point of concern is: will be the involved countries be able to repay their debt to China? Let’s take Pakistan for an example. The estimated cost of the Chinese-Pakistan corridor has an estimated cost of $62bn, 55 of which kindly provided by China. Recently, for the 13th time in 30 years, Pakistan has announced that it will ask a bailout from the IMF, for a loan up to $7bn, vital to ‘keep the lights on’ (no joke: without this loan from IMF, Pakistan will not be able to pay for the electricity it imports).

How will it be possible for a country in this economic distress to repay such a loan? Many international experts worry that this will give China the power to take a stake in Pakistan’s economic decisions in future, threatening sovereign powers. But it is not over yet: the main beneficiary of this corridor will be China, and not Pakistan, since this strategic node will allow the former to export in Europe, while the latter has nothing to export. Pakistan is not the only one: other countries such Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Vietnam and Cambodia are facing similar situation.

It would be unfair to say that the OBOR will not bring economic growth: it will probably boost trades and create jobs. However, it is difficult to say what the price of this project will be: China will extend its influence further not only in Asia but also in Europe, controlling de facto what will become the main infrastructure network in the world. Moreover, it will have a huge stake in the public debt of many Asian countries and to predict the possible political consequences is a tricky task.

Riccardo Ronzani

How will it be possible for a country in this economic distress to repay such a loan? Many international experts worry that this will give China the power to take a stake in Pakistan’s economic decisions in future, threatening sovereign powers. But it is not over yet: the main beneficiary of this corridor will be China, and not Pakistan, since this strategic node will allow the former to export in Europe, while the latter has nothing to export. Pakistan is not the only one: other countries such Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Vietnam and Cambodia are facing similar situation.

It would be unfair to say that the OBOR will not bring economic growth: it will probably boost trades and create jobs. However, it is difficult to say what the price of this project will be: China will extend its influence further not only in Asia but also in Europe, controlling de facto what will become the main infrastructure network in the world. Moreover, it will have a huge stake in the public debt of many Asian countries and to predict the possible political consequences is a tricky task.

Riccardo Ronzani