The European Union has been a great economic powerhouse for decades. It has successfully united multiple nations under one monetary policy regime alongside strict fiscal policy monitoring. However, since the creation of the EU, individual countries have struggled to successfully integrate fiscal policy recommendations into their own policies and laws. The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was among the first attempts to draft a unified fiscal policy, but the ‘one-size-fits-all' policy approach has been scrutinized by member countries as it does not address nation-tailored objectives. The European Commission has advised to reduce the inflexibility with distinguishing countries by their pre-existing debt and improving surveillance and reduction of debt levels. This article will present the history of EU’s fiscal policy development, current issues, what solutions may be applied, following the impact of the proposals.

History of fiscal policy in the EU from its creation

The creation of the European Union (EU) began with the European Economic Community back in 1957 among 6 countries to help with trade cooperation within the region. The union among these countries, with some other new members, became closer resulting in the creation of the European Union in 1992 along the Treaty of Maastricht. This Treaty introduced the idea of the euro and the limitation of government deficits and public debt levels. Closer economic ties and common fiscal policy aimed to facilitate trade among countries and foster economic growth. More specifically, with the Treaty it was hoped to create a common European citizenship, allowing residents to freely move, work, trade, and invest in the member states. Additionally, under the agreement arose the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), introducing not only the euro but a European Central Bank, managing the general basis of monetary policy for these countries, hoping to maintain price stability. For new countries to join the EU, the Maastricht criteria were drafted: inflation rate could not be greater than 1.5 points of the best-performing member country, annual government deficit should be less than 3% of GDP, debt should not be greater than 60% of GDP, currency must not be devalued, and longer-term interest rates cannot exceed more than 2% of the three best-performing countries’ average. Five years later, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) is introduced to “strengthen the surveillance and coordination of national fiscal and economic policies to enforce the Maastricht rules”. Over the following years the SGP corrective (clarifying implementation) and preventive (strengthening surveillance) arms were introduced. However, the policy did not go without its scandals, with the European Commission accusing France and Germany of not sticking to the rules.

In 2005 the first amendments were presented to “better consider individual national circumstances”, due to the complaints of trying to apply one policy to all countries, when countries were of varied development and their economies focused on different sectors. The parameters remained unchanged; however, excessive deficit criteria were reformed, considering the level of debt, the budget activity during cycles and others. After the 2008 financial crisis it was clear the pact needed further amendments for monitoring and strengthening the adherence to the SGP – Fiscal Compact, Six Pack and Two Pack. The significant reforms of the SGP were deemed controversial because of limited sovereignty, once again reducing the fiscal flexibility of nations. Six Pack mainly focused on reducing macroeconomic imbalances and maintaining the viability of countries’ finances through either preventive or corrective actions, whereas the Two Pack addressed the expansion of applying the Six Pack, through budget coordination in terms of time and rules, and improving surveillance of more financially troubled countries. In 2020, the second review of these pack of rules was launched, looking for areas of improvement, specifically regarding macroeconomic surveillance. Covid-19 too had its impact, where member countries were exempted from the budget requirements, due to the unprecedented situation, showing the flaws of the regulation, with the EPC task force even saying, would likely be politically, socially and economically untenable in countries with high debt levels, hence once again a one-size-fits-all policy to debt reduction would not work, requiring the European Union to reconsider its current fiscal policy and address the needs of each sovereign member state.

What are the main problems of the current fiscal policy

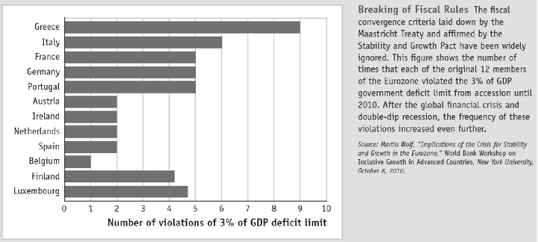

As discussed, a main criticism on the SGP is that it is composed by general, all-applicable, and inflexible rules that apply to all EU countries and do not consider country-specific economic factors and consequently undermine the credibility of the SGP. For instance, this results in a large number of violations by EU states of this rule, as is depicted in Figure 1 below. One example of its inflexibility is that is does not take into account the specific phase of the economic cycle that a country is experiencing. For instance, during a recession, a 3% deficit ceiling may not be sufficient to stimulate growth, while during periods of economic growth, the same deficit limit may seem like a high threshold that few states will reach. Therefore, it is important to account for economic cycles when forcing certain fiscal policies.

Figure 1: Breaches of EU fiscal policy

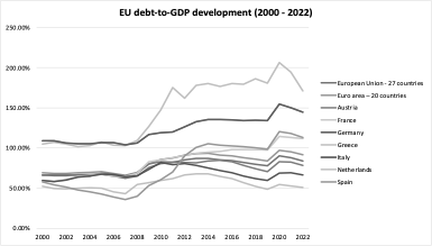

The current incentives provided by the rules are not sufficient to encourage fiscal restraint during periods of high economic growth since there is no reward for keeping the deficit below the limit. The possibility of facing fines for breaking the deficit rule during an economic downturn did not have a significant impact on government behaviour during times of economic prosperity, as the next recession may seem distant and could potentially occur under a different government. Additionally, research suggests that the Pact's rules may have encouraged pro-cyclical fiscal policies. This is in contrast with economic theory which suggests that fiscal policy should be counter-cyclical, incurring a budget deficit in downturns and a surplus in booms. This has led to substantial debt increases already, as is shown in Figure 2.

The midterm goals set by the SGP that say that a country should have a budget ‘close to balance or in surplus’ have only been introduced in 2011 and there is still not enough data to judge their effectiveness, but it can already be seen that most countries have never met this midterm objective. It might be due to the reason that there is no clear guide path for countries helping achieve this goal and current governments shift the responsibility for that onto the next governments.

Finally, there is the “debt rule” which requires EU member states to maintain a debt to GDP ratio below 60% and if a country’s ratio is above 60% than they are forced to cut their debt annually by one-twentieth of the gap between where their total debt is and where it is supposed to end up. However, many countries in the EU zone are already above this threshold, which is causing significant harm to their economies.

The midterm goals set by the SGP that say that a country should have a budget ‘close to balance or in surplus’ have only been introduced in 2011 and there is still not enough data to judge their effectiveness, but it can already be seen that most countries have never met this midterm objective. It might be due to the reason that there is no clear guide path for countries helping achieve this goal and current governments shift the responsibility for that onto the next governments.

Finally, there is the “debt rule” which requires EU member states to maintain a debt to GDP ratio below 60% and if a country’s ratio is above 60% than they are forced to cut their debt annually by one-twentieth of the gap between where their total debt is and where it is supposed to end up. However, many countries in the EU zone are already above this threshold, which is causing significant harm to their economies.

Figure 2: EU Debt-to-GDP development

Italy is a prime example of a country struggling with high debt, with a debt to GDP ratio of almost 150%. According to the SGP, they would have to lower their debt by 4.5% annually. To comply with the rule, the Italian government would have to implement significant spending cuts and tax increases, further damaging their already struggling economy. Additionally, potential sanctions for not abiding the rule’s reduction number would only worsen their economic environment.

What is being proposed

Many politicians, policymakers, and scholars now agree that the EU fiscal rules need to be reformed. Currently the EU fiscal policies are overly complex, and they drive governments of the member states to overspend during economic boom and underspend during recessions. To reform the SGP, the European Commission (EC) is suggesting to focus mainly on surveillance and the reduction of debt levels. Two are the main improvements being proposed. The first one is to design the process itself by structuring it around the projected development of public debt. The second is to distinguish among countries based on their pre-existing debt. Looking at fiscal policy, it is very important to underline that it is an intertemporal issue, not a year-after-year issue. With these proposals, the EC is recognizing that debt sustainability is a task that requires a considerable amount of time. In particular, the procedure proposed by the EC is focused on the analysis of the debt path.

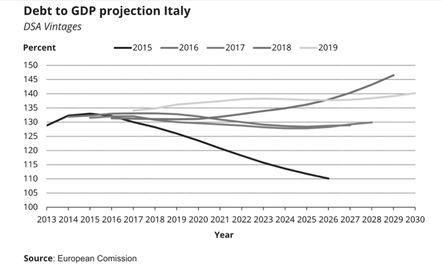

Figure 3: Debt-to-GDP projection for Italy

A major role from this point of view is played by the so-called debt sustainability analysis (DSA). On the one hand the DSA is a crucial tool, but on the other hand it has some downsides that should be underlined. In particular, the DSA is not an apolitical algorithm since it is a tool that calculates the debt evolution given certain assumptions and a settled time horizon. The EC proposed a four-year horizon. This choice has been widely criticized on the ground that it is a too short time horizon, which could have perverse effects including inducing member states to cut government spending in an economic slowdown. The EC, to prevent criticism on this point, has included in the proposal the possibility to extend the timeframe to seven years under certain assumptions. Another very important concern related to this instrument is that the EC decides the assumptions. More specifically, the trajectory of the debt-GDP-ratio is shaped by three variables: the real interest rate of the debt service, the real income growth rate, and the deficit ratios, year after year. Future paths of these variables are complex to predict, and this has led to assumptions about their prospective development. The role of the EC in shaping these assumptions has led to a situation in which the EC itself decides if a debt path is sustainable or not. In addition, the EC proposals don’t take into consideration the fact that national independent fiscal councils have been created by different state members to supervise their government budgets, even if some of them are not fully independent. National independent fiscal councils could have a greater role in taking ownership in the fiscal field and this would mean imposing proper controls over the work of these bodies and consequently reduce the role of the EC. When the EC was involved in the public consultation, France’s President Emmanuel Macron and the former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi discussed the EU-budget rules in an Opinion article and argued for more flexibility to stimulate investment and long-term growth. Contrary, the Germany’s Ministers of Finance, recently wrote that “numerical benchmarks are a minimum requirement for ensuring declining debt ratios and equal treatment”. Economists have been arguing about the introduction of a golden rule, allowing certain investments such as green projects to be favoured by the fiscal rule, as well as debt raised to fund investment priorities. The EC has so far been resistant to the implementation of the Golden Investment Rule arguing that it would not fit into the fiscal framework of the stability Budget.

Short and long run effects of the proposal

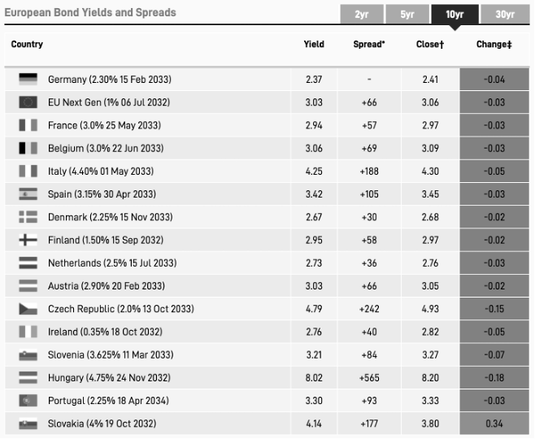

Although it remains an ongoing international discussion on what is defined an unsustainable debt level, the substantial difference in fiscal positions of EU countries is a weakness to the coherency of the Union. Frugal members in the EU, comprising Germany, Netherlands, and Austria at the forefront, insist on inflexible numerical debt-reduction targets. Southern countries, like France and Italy argue for potentially too lenient rules concerning accounting standards for government investments. The future of the EU and its economic relevance for a large part of the 21st century will be defined by the outcomes of the current negotiations on fiscal policy reform. In the short run, commitment of the frugal countries to create a more effective and robust fiscal policy framework help to further stabilize the interest rates on high indebted countries. The commitment would signal to the bond market participants a strengthened unity and boost confidence, likely to decrease spreads with the German government bond yield, the standard EU benchmark. Meanwhile, the framework needs to keep countries in line too, since too lenient rules could signal a worsening of government credit. At the time of writing, the bond spread between Germany and Italy is nearly two percentage points, while it’s difference with the Dutch bonds is only 0.36 percentage points (Figure 4). We consider this the positive scenario. Alternatively, in a neutral scenario, if member states cannot agree on establishing functional rules, the EU might stumble further with ineffective rules, which would maintain the status quo likely or increase spreads slightly. Unlikely, but possible, in a negative scenario, where disagreement develops in fundamental bursts in the EU, credit spreads could increase.

Short and long run effects of the proposal

Although it remains an ongoing international discussion on what is defined an unsustainable debt level, the substantial difference in fiscal positions of EU countries is a weakness to the coherency of the Union. Frugal members in the EU, comprising Germany, Netherlands, and Austria at the forefront, insist on inflexible numerical debt-reduction targets. Southern countries, like France and Italy argue for potentially too lenient rules concerning accounting standards for government investments. The future of the EU and its economic relevance for a large part of the 21st century will be defined by the outcomes of the current negotiations on fiscal policy reform. In the short run, commitment of the frugal countries to create a more effective and robust fiscal policy framework help to further stabilize the interest rates on high indebted countries. The commitment would signal to the bond market participants a strengthened unity and boost confidence, likely to decrease spreads with the German government bond yield, the standard EU benchmark. Meanwhile, the framework needs to keep countries in line too, since too lenient rules could signal a worsening of government credit. At the time of writing, the bond spread between Germany and Italy is nearly two percentage points, while it’s difference with the Dutch bonds is only 0.36 percentage points (Figure 4). We consider this the positive scenario. Alternatively, in a neutral scenario, if member states cannot agree on establishing functional rules, the EU might stumble further with ineffective rules, which would maintain the status quo likely or increase spreads slightly. Unlikely, but possible, in a negative scenario, where disagreement develops in fundamental bursts in the EU, credit spreads could increase.

Figure 4: European Bond Yields and Spreads

In the medium run, effective and robust fiscal rules can lead heavily indebted countries like Italy and Greece to reduce their debt levels. In the past, numerous Western countries have significantly reduced their debt levels. Belgium decreased its debt-to-GDP ratio by more than 50% over 14 years with modest annual growth of 2.5%. Favourable conditions such as moderate inflation and low(er) interest rates can speed this transition, as a country can effectively grow out of its debt, but these are not necessary requirements for debt reduction. Another example is Greece, which although still having the largest debt-to-GDP ratio in Europe is significantly improving through fiscal surpluses and productive investments. Its government bonds are expected to be labelled ‘investment grade’ later this year for the first time in 12 years.

The so-called golden rule for investment expenditures could in theory boost productive investments and consequently economic growth, so that the countries can grow themselves out of debt. A big concern, however, with this rule is that the definition of a ‘productive’ investment is dubious. A politician aiming to win re-election might consider favouring a certain group through what could be a productive investment for this person and his party, but not for the wider economy. Considering other potential legislative reforms, these should leave less space for politicians to manoeuvre the rules in their political favour and still boost growth. In contrast, it could encourage them to pursue long-term welfare enhancing policies that still leave space for the democratic processes that are inherent to fiscal policy decisions.

The so-called golden rule for investment expenditures could in theory boost productive investments and consequently economic growth, so that the countries can grow themselves out of debt. A big concern, however, with this rule is that the definition of a ‘productive’ investment is dubious. A politician aiming to win re-election might consider favouring a certain group through what could be a productive investment for this person and his party, but not for the wider economy. Considering other potential legislative reforms, these should leave less space for politicians to manoeuvre the rules in their political favour and still boost growth. In contrast, it could encourage them to pursue long-term welfare enhancing policies that still leave space for the democratic processes that are inherent to fiscal policy decisions.

Conclusion

After 30 years, it is time for the EU to reform its fiscal policy framework. The original Maastricht Treaty and SGP that followed having seen numerous revisions and updates but failed to realistically adjust existing inflexible rules. The inflexibility of the rules with a 60% debt-to-GDP ratio target and a norm 3% for budget deficits lead to implausible debt reduction target, which undermine the credibility of the fiscal framework and the EC more broadly. Since the Maastricht Treaty, many countries have breached the fiscal rules without facing consequences in terms of fines or punishments form the Union. Partly due to the lacking enforcement and incentives to follow the rules, debt-to-GDP in the EU has grown from 66% in 2000 to 84% in 2022. Politicians across the aisle agree that there must be a change. Politicians from Southern countries advocate for more lenient rules that allow for more flexibility, whereas Northerners tend to argue in favour – as the German Minister of Finance did – for numerical benchmarks that allow for strict calculations on debt reduction targets. One way would be to include a Golden investment rule, but it is unclear what would be defined as growth-enhancing investment under this rule. Alternatively, national fiscal councils should receive more power as these can better independently conduct analyses for their respective countries. This also takes it away from the bureaucratic EC, which can avoid conflict. Resulting, when the EU countries would agree on rules that lay out a credible and robust framework this could boost unity and confidence in the bond markets – particularly for highly indebted countries. Much depends on the future of this framework; with the right reforms this could lead to drastic economic improvements in the EU with strong implications for its economic position in the world for the rest of this century.

By Willem van der Mee, Maxim Shkolnikov, Vasara Silininkaite, Najwa Sadki

SOURCES:

- European Commission

- Financial Times

- Investopedia

- Centre for Economic Policy Research

- The Economist

- Centre for European Reform