Introduction

The pandemic has highlighted the UK's strong leadership position in the scientific field and represented a turning point for the government to recognize the central role of science in the future of the country. The investments envisaged by Boris Johnson aim at transforming the UK, with the goal of making it a “science superpower”. Confident about these ambitions, many of the world’s biggest property investors are investing billions in the British life sciences industry. The article analyses the government plans to achieve the science superpower status and the potential setbacks it could face.

The path to reach the “science superpower” status

Boris Johnson, British prime minister, has the ambition to turn Britain into a "scientific superpower", building on the country's achievements in green energy and the development of the Oxford-AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine. Harwell campus, in England, is the symbol of his aim.

The 700-acre site in rural Oxfordshire has become a center of research and development in disciplines such as space, sustainable energy, quantum computing, and life sciences, having obtained about £3 billion in public and private funding.

The UK Vaccines Manufacturing and Innovation Centre, a university-industry collaboration sponsored by £196 million in government funding to foster expansion of the UK vaccines industry, is the newest addition to the campus.

The pandemic has highlighted the UK strong leadership position in the scientific field, but it has also exposed several British flaws, such as a lack of vaccine manufacturing capability and other high-tech areas.

According to Sir Jim McDonald, president of the Royal Academy of Engineering, the country's premier engineering professional organization, the UK research base already makes them a science superpower but this alone is not enough. The scientist reckons that Britain has the capability to become a science, technology, and innovation superpower by creating a virtuous circle of growth between the research base and industry.

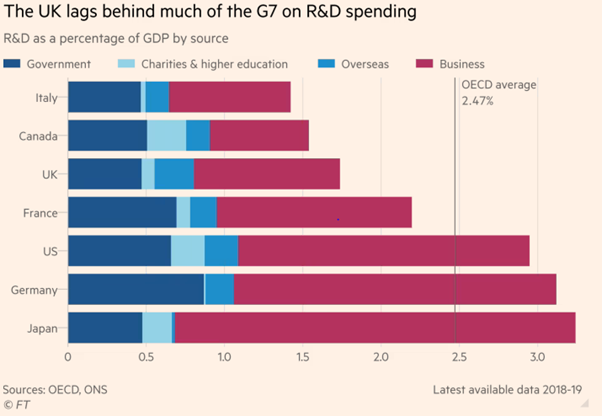

The government's expenditure plans aim to end the UK's status as a G7 laggard by increasing public investment in R&D from £14.9 billion in 2021 to £22 billion in 2024-25. By 2027, total UK R&D investment by the public and commercial sectors is expected to rise from 1.7 percent of GDP today to 2.4 percent, which is the average for industrialized countries.

The pandemic has highlighted the UK's strong leadership position in the scientific field and represented a turning point for the government to recognize the central role of science in the future of the country. The investments envisaged by Boris Johnson aim at transforming the UK, with the goal of making it a “science superpower”. Confident about these ambitions, many of the world’s biggest property investors are investing billions in the British life sciences industry. The article analyses the government plans to achieve the science superpower status and the potential setbacks it could face.

The path to reach the “science superpower” status

Boris Johnson, British prime minister, has the ambition to turn Britain into a "scientific superpower", building on the country's achievements in green energy and the development of the Oxford-AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine. Harwell campus, in England, is the symbol of his aim.

The 700-acre site in rural Oxfordshire has become a center of research and development in disciplines such as space, sustainable energy, quantum computing, and life sciences, having obtained about £3 billion in public and private funding.

The UK Vaccines Manufacturing and Innovation Centre, a university-industry collaboration sponsored by £196 million in government funding to foster expansion of the UK vaccines industry, is the newest addition to the campus.

The pandemic has highlighted the UK strong leadership position in the scientific field, but it has also exposed several British flaws, such as a lack of vaccine manufacturing capability and other high-tech areas.

According to Sir Jim McDonald, president of the Royal Academy of Engineering, the country's premier engineering professional organization, the UK research base already makes them a science superpower but this alone is not enough. The scientist reckons that Britain has the capability to become a science, technology, and innovation superpower by creating a virtuous circle of growth between the research base and industry.

The government's expenditure plans aim to end the UK's status as a G7 laggard by increasing public investment in R&D from £14.9 billion in 2021 to £22 billion in 2024-25. By 2027, total UK R&D investment by the public and commercial sectors is expected to rise from 1.7 percent of GDP today to 2.4 percent, which is the average for industrialized countries.

Source: Financial Times

However, this massive increase in the nation's R&D spending is expected to be obstructed in the UK Budget and the predicted figures for public investments by 2024 are unlikely to be realized anytime soon. Whitehall officials are skeptical of the economic benefits of such high levels of spending.

However, following a period in which most of the UK's population, as the rest of the world, owes their health to Britain's scientific competence, it would be a great mistake to back off on research funding. The UK is home to some of the world's best scientists and scientific institutes, as well as a long history of innovation.

The science minister George Freeman, a former biotech entrepreneur, is aiming to reinforce the agenda as well. Freeman intends to leverage R&D to spread prosperity across the country, as well as securing funds to improve the UK's international status in research. His aim is to generate new clusters of scientific development, in parts of the country as far less important for this kind of projects. His fight against inequality between developed and non developed regions, though, is going to be a hard challenge in choosing between national and international benefits. Indeed, right now, about 50% of government spending in scientific research is going to the “golden triangle” of London, Oxford and Cambridge. Investing in other regions of the country may reduce inequality, but it might slow down the British race to gain a premiere position in the scientific world.

The Oxford-Cambridge Arc

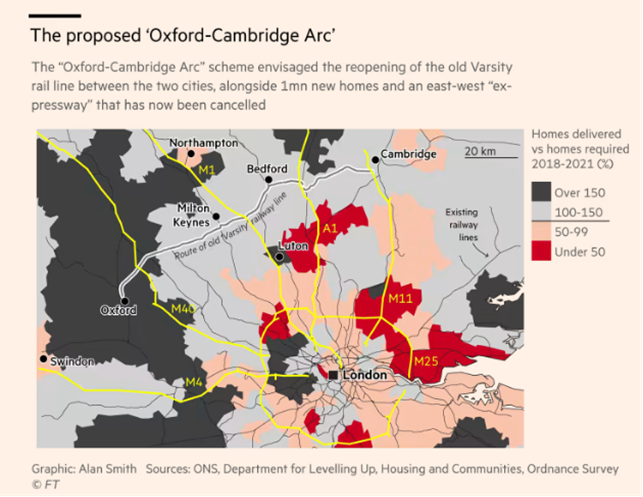

Among the missions pursued by Boris Johnson, strong political support was given to the funds allocated for expansion that goes beyond the golden triangle of Oxford-London-Cambridge and prioritizes “leveling up” spending in the north of England. As a result, the plan to create a rival of the Silicon Valley around Oxford and Cambridge was momentarily put on hold. We are talking about the Oxford-Cambridge Arc, the strategic plan for the construction of a support infrastructure to connect the two main university cities of the United Kingdom, extending from Oxford to Cambridge but also passing through Bicester, Milton Keynes and Bedford. Billed as the British version of Silicon Valley, it aims to create an arc that brings together the region's academic, innovation, development and research resources to drive and revive UK growth, while keeping the ambition to turn Britain into a "scientific superpower".

The original Arc Oxford to Cambridge (O2C) initiative was first launched in 2003 by three UK regional development agencies (RDAs), EEDA, EMDA and SEEDA with the aim of accelerating the business and entrepreneurial activity that characterized the territory. Support from the Government came in 2017, when a plan was drawn up by the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) proposing a massive investment consisting of an Oxford - Cambridge Expressway road link, a Cambridge to Bedford railway, with the aim of building an east-west rail link, and a million new homes and jobs within the Arc, increasing average worker productivity by £6,000 by 2050.

However, following a period in which most of the UK's population, as the rest of the world, owes their health to Britain's scientific competence, it would be a great mistake to back off on research funding. The UK is home to some of the world's best scientists and scientific institutes, as well as a long history of innovation.

The science minister George Freeman, a former biotech entrepreneur, is aiming to reinforce the agenda as well. Freeman intends to leverage R&D to spread prosperity across the country, as well as securing funds to improve the UK's international status in research. His aim is to generate new clusters of scientific development, in parts of the country as far less important for this kind of projects. His fight against inequality between developed and non developed regions, though, is going to be a hard challenge in choosing between national and international benefits. Indeed, right now, about 50% of government spending in scientific research is going to the “golden triangle” of London, Oxford and Cambridge. Investing in other regions of the country may reduce inequality, but it might slow down the British race to gain a premiere position in the scientific world.

The Oxford-Cambridge Arc

Among the missions pursued by Boris Johnson, strong political support was given to the funds allocated for expansion that goes beyond the golden triangle of Oxford-London-Cambridge and prioritizes “leveling up” spending in the north of England. As a result, the plan to create a rival of the Silicon Valley around Oxford and Cambridge was momentarily put on hold. We are talking about the Oxford-Cambridge Arc, the strategic plan for the construction of a support infrastructure to connect the two main university cities of the United Kingdom, extending from Oxford to Cambridge but also passing through Bicester, Milton Keynes and Bedford. Billed as the British version of Silicon Valley, it aims to create an arc that brings together the region's academic, innovation, development and research resources to drive and revive UK growth, while keeping the ambition to turn Britain into a "scientific superpower".

The original Arc Oxford to Cambridge (O2C) initiative was first launched in 2003 by three UK regional development agencies (RDAs), EEDA, EMDA and SEEDA with the aim of accelerating the business and entrepreneurial activity that characterized the territory. Support from the Government came in 2017, when a plan was drawn up by the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) proposing a massive investment consisting of an Oxford - Cambridge Expressway road link, a Cambridge to Bedford railway, with the aim of building an east-west rail link, and a million new homes and jobs within the Arc, increasing average worker productivity by £6,000 by 2050.

Source: Financial Times

"We have start-up companies and spin-off companies from the universities looking for space," said Mike Derbyshire. Head of planning at property consultants Bidwells argues that the Arc is essential to freeing up new land for developing companies and for companies such as Apple, Samsung, Miscrosoft and AstraZeneca, which are looking for additional space.

The region is a highly successful network of places, rich in productivity and with high growth potential. The investments make it possible to improve the science and technology of the country, increasing the competitive growth of the world's leading industries. Thus, the Oxford Cambridge Arc, according to the Chancellor of Exchequer, is a "key economic priority" to allow the United Kingdom to pursue its role as a leading global innovation region.

"If indeed we are trying to compete globally with places like Boston, we should be backing areas that already have the advantage of universities and an educated workforce. If we don't have that collaboration, if we don't have that effort to join up, then my worry is that we will still have the acceptance of unsustainable growth - it will still happen, but won't bring our communities with us and the growth won't be in areas where our innovation can change things " Bev Hindle said.

It seems clear that the Arc represents a bold vision to create a global hub for innovation and green development that inspires communities worldwide and despite the NIC claiming that the new road and the East-West Rail project had to "be built as quickly as possible to unlock land for new homes ", in the area covered by the Arc, the opposition of parliamentarians, environmentalists and people who lived in development areas did not stand aside.

In this regard, the Conservative MP for North East Bedfordshire Richard Fuller opposed the plan and told BBC Politics East that the project was based on an imperfect thesis rather than focusing on improving transport links with satellite cities around Oxford and Cambridge. Furthermore, he added: “It was a pretext really for additional houses. For the communities to take more housing and for the connectivity to justify one million more homes. We are already under too much pressure from housing and that means pressure to get GP appointments or a school place. I think the underpinnings of the Arc failed from the start and I hope it is being downplayed."

Despite the opposition, the benefits that would derive from the Arc for the United Kingdom are not only measurable in economic terms, the investments would also turn into social returns that would far exceed the monetary returns.

Although the advantage that the United Kingdom could derive from an implementation of the Project for the construction of the Oxford Cambridge Arc seems so evident, it seems that the Government is blindfolded. Boris Johnson has shelved the strategic plan for the construction of the British rival Silicon Valley around Oxford and Cambridge, leaving room for the "levelling up" expenditure in the north of England.

Indeed, the British prime minister during his election in 2019 had presented a "levelling up" program promising to focus on economic growth outside of London and the South East.

Tories' shock by-election defeat in nearby Chesham & Amersham last year also pushed Johnson further to abandon plans to upgrade British housing, leaving them in the hands of fragmented local councilors.

The project is no longer considered a priority by ministers and Michael Gove, the secretary for the level crossing, indicated that the Arch is now in the background and, despite the construction of a railway line between Oxford and Cambridge, the 1 million home target and the East-West Road have been shelved.

A research report said the UK's decision risks costing the UK economy approximately £50 billion. Real estate consultancy Bidwells and Blackstock Consulting estimate that investments over the span would increase cumulative production in the region from £185 billion to £235 billion by 2030. According to the Financial Times, among those who are most urging the government to harness the Arc and the potential growth it could bring are Santander UK, L&G, Wellcome-Sanger Institute, Abcam, Harwell and AstraZeneca.

"The Arc needs government support - the aspiration to make this a global supercluster and a leading innovation geography will only work if there's appropriate infrastructure in place, from funding, to transport, to housing" said Michael Anstey, a partner at Cambridge Innovation Capital.

Demand continues to grow, and early action is required to avoid being left behind.

However, the actions of the British government seem not to match their ambitions: the United Kingdom still has a long way to go before becoming a "scientific superpower".

Private investments into the “science superpower” UK

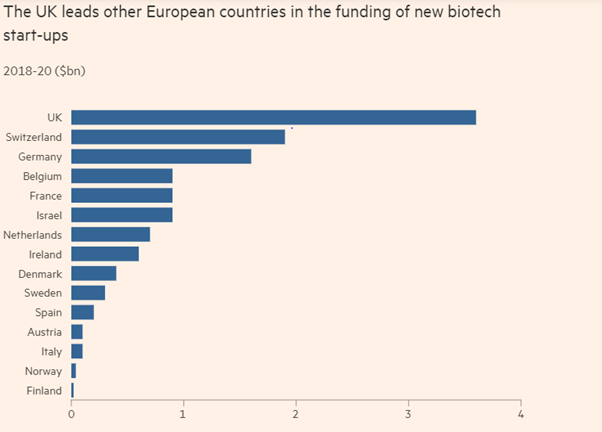

The strong focus and support given by the British government to the life sciences industry, coupled with world famous top-tier universities and research centers, have continuously attracted private funding from global investors. In particular, between 2018 and 2020, the UK received $3.6bn of investment into biotech startups through IPOs and venture capital- the most in Europe ($1.7bn more than Switzerland, in second).

The region is a highly successful network of places, rich in productivity and with high growth potential. The investments make it possible to improve the science and technology of the country, increasing the competitive growth of the world's leading industries. Thus, the Oxford Cambridge Arc, according to the Chancellor of Exchequer, is a "key economic priority" to allow the United Kingdom to pursue its role as a leading global innovation region.

"If indeed we are trying to compete globally with places like Boston, we should be backing areas that already have the advantage of universities and an educated workforce. If we don't have that collaboration, if we don't have that effort to join up, then my worry is that we will still have the acceptance of unsustainable growth - it will still happen, but won't bring our communities with us and the growth won't be in areas where our innovation can change things " Bev Hindle said.

It seems clear that the Arc represents a bold vision to create a global hub for innovation and green development that inspires communities worldwide and despite the NIC claiming that the new road and the East-West Rail project had to "be built as quickly as possible to unlock land for new homes ", in the area covered by the Arc, the opposition of parliamentarians, environmentalists and people who lived in development areas did not stand aside.

In this regard, the Conservative MP for North East Bedfordshire Richard Fuller opposed the plan and told BBC Politics East that the project was based on an imperfect thesis rather than focusing on improving transport links with satellite cities around Oxford and Cambridge. Furthermore, he added: “It was a pretext really for additional houses. For the communities to take more housing and for the connectivity to justify one million more homes. We are already under too much pressure from housing and that means pressure to get GP appointments or a school place. I think the underpinnings of the Arc failed from the start and I hope it is being downplayed."

Despite the opposition, the benefits that would derive from the Arc for the United Kingdom are not only measurable in economic terms, the investments would also turn into social returns that would far exceed the monetary returns.

Although the advantage that the United Kingdom could derive from an implementation of the Project for the construction of the Oxford Cambridge Arc seems so evident, it seems that the Government is blindfolded. Boris Johnson has shelved the strategic plan for the construction of the British rival Silicon Valley around Oxford and Cambridge, leaving room for the "levelling up" expenditure in the north of England.

Indeed, the British prime minister during his election in 2019 had presented a "levelling up" program promising to focus on economic growth outside of London and the South East.

Tories' shock by-election defeat in nearby Chesham & Amersham last year also pushed Johnson further to abandon plans to upgrade British housing, leaving them in the hands of fragmented local councilors.

The project is no longer considered a priority by ministers and Michael Gove, the secretary for the level crossing, indicated that the Arch is now in the background and, despite the construction of a railway line between Oxford and Cambridge, the 1 million home target and the East-West Road have been shelved.

A research report said the UK's decision risks costing the UK economy approximately £50 billion. Real estate consultancy Bidwells and Blackstock Consulting estimate that investments over the span would increase cumulative production in the region from £185 billion to £235 billion by 2030. According to the Financial Times, among those who are most urging the government to harness the Arc and the potential growth it could bring are Santander UK, L&G, Wellcome-Sanger Institute, Abcam, Harwell and AstraZeneca.

"The Arc needs government support - the aspiration to make this a global supercluster and a leading innovation geography will only work if there's appropriate infrastructure in place, from funding, to transport, to housing" said Michael Anstey, a partner at Cambridge Innovation Capital.

Demand continues to grow, and early action is required to avoid being left behind.

However, the actions of the British government seem not to match their ambitions: the United Kingdom still has a long way to go before becoming a "scientific superpower".

Private investments into the “science superpower” UK

The strong focus and support given by the British government to the life sciences industry, coupled with world famous top-tier universities and research centers, have continuously attracted private funding from global investors. In particular, between 2018 and 2020, the UK received $3.6bn of investment into biotech startups through IPOs and venture capital- the most in Europe ($1.7bn more than Switzerland, in second).

Source: Financial Times

This trend has been accelerated by the Covid-19 crisis, which coincided with a time of massive growth in the UK biotech industry. Indeed, the country saw 22 new firms founded over the course of the pandemic, as well as a major strengthening of its reputation through projects such as the Oxford-AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine.

The science industry has also seen major investment from property developers such as Tishman Speyer, who partnered with Bellco Capital, a biotech investment firm. The consortium, known as Breakthrough Properties, estimates that their venture to construct laboratories and offices may result in upwards of $5bn in spending- a major cash injection into the UK’s life sciences industry.

In addition to that, another investor - Canadian Brookfield Asset Management - has developed a life sciences property platform focused on the UK. This combines the firm’s existing UK assets including the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus. Moreover, the Asset Management firm aims to invest additional £1.5bn-£2bn to develop more lab and office spaces.

However, the majority of property investment targeting life sciences has been mainly addressed to the Oxford-Cambridge Arc and investors urge the Government to maintain their interests there. The maximization of the Arc’s potential is vital to attract private investments which in turn is necessary to reach the “science superpower” status. Inevitably, this poses a lot of pressure on the Government which will need to make a compromise between its desire to “level up” the country and the goal to make the UK the next scientific leader.

Sources:

- BBC

- Financial Times

- OxLEP

By Matthew Gleeson, Anna Rosaria Manni, Cosimo Winchler