Introduction

Founded more than a hundred year ago, Unilever represents nowadays one of the biggest consumer goods companies in the world. It operates in about 190 countries, has more than 140.000 employees and according to their website more than 3.4 billion people use their products on a daily basis.

At the end of the year 2021 the management of Unilever started several tries to acquire a consumer health business which would have been one of the largest buyouts in Europe ever. The failed attempt led to immense pressure by shareholders afterwards and restructuring in the firm.

The attempt to acquire GSK and why it failed

In December Unilever tried with three different proposals to convince the GSK board to acquire their consumer unit which is a joint-venture between GSK (owns 68%) and Pfizer (owns 32%). In their last proposal they offered £50bn, of which £41.7bn would be paid in cash and £8.3bn in stocks.

Unilever faced slow internal growth, and the consumer goods unit represented a strong strategic fit as the company tries to reshape its portfolio, which contains more than 400 different brands.

Nevertheless, the board from GSK rejected all offers and commented they failed all to reflect the real value and were “fundamentally undervalued”. In accordance with a person close to Pfizer, an offer of £60bn would be hard to reject, which would reflect an estimated 25% premium for the business. One of the main problems were different points of views on the valuation and future growth rates. Most analysts estimate moderate growth rates between 3-4%, though GSK is expecting rates between 4-6%. This pushes the intrinsic value dramatically from £37bn to £48bn. In January, Unilever said it would not increase its offer after a huge counter-reaction by big stakeholders who were against the transaction.

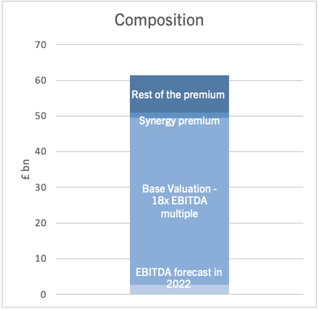

Here are the assumptions for a competitive offer for the consumer health unit according to a person close to the owners:

Founded more than a hundred year ago, Unilever represents nowadays one of the biggest consumer goods companies in the world. It operates in about 190 countries, has more than 140.000 employees and according to their website more than 3.4 billion people use their products on a daily basis.

At the end of the year 2021 the management of Unilever started several tries to acquire a consumer health business which would have been one of the largest buyouts in Europe ever. The failed attempt led to immense pressure by shareholders afterwards and restructuring in the firm.

The attempt to acquire GSK and why it failed

In December Unilever tried with three different proposals to convince the GSK board to acquire their consumer unit which is a joint-venture between GSK (owns 68%) and Pfizer (owns 32%). In their last proposal they offered £50bn, of which £41.7bn would be paid in cash and £8.3bn in stocks.

Unilever faced slow internal growth, and the consumer goods unit represented a strong strategic fit as the company tries to reshape its portfolio, which contains more than 400 different brands.

Nevertheless, the board from GSK rejected all offers and commented they failed all to reflect the real value and were “fundamentally undervalued”. In accordance with a person close to Pfizer, an offer of £60bn would be hard to reject, which would reflect an estimated 25% premium for the business. One of the main problems were different points of views on the valuation and future growth rates. Most analysts estimate moderate growth rates between 3-4%, though GSK is expecting rates between 4-6%. This pushes the intrinsic value dramatically from £37bn to £48bn. In January, Unilever said it would not increase its offer after a huge counter-reaction by big stakeholders who were against the transaction.

Here are the assumptions for a competitive offer for the consumer health unit according to a person close to the owners:

Certainly, any offer higher than £50B would have brought Unilever in trouble to finance the deal. The company itself already has a relatively high leverage ratio and a potentially higher future one since most of the deal would have been financed with cash. “Unilever already has relatively high leverage, and by paying largely in cash, you would have a highly levered new company that would have to focus for years on paying debt rather than driving growth” said Bruno Monteyne, an analyst at Bernstein. Another analyst from Wall Street pointed out that an all-cash deal for £55bn would have brought the Debt/EBITDA ratio from currently roughly 3 up to 5. Therefore also the rating agency Fitch pointed out that in case of an increasing level of debt due to the acquisition, the company might be downgraded on their investment-grade rating from A to BBB.

In any case, the GSK management was planning to spin-off the business in mid-2022 after pressure from several shareholders, including the US hedge fund Elliott Management. The knock-out argument for a spin-off is that it would be tax-free. Selling the unit would likely reduce the net profit for GSK and other shareholders due to a significant tax-bill. However, this could potentially be mitigated and a demerger from this size would be expected to take longer since regulators would overview and review the transaction.

As financial advisors served Deutsche Bank and Centerview Partners towards Unilever and Goldman Sachs towards GSK.

The role of (activist) investors after the failed M&A transaction

The £50bn failed bid raised several questions about the company’s strategy under the leadership of CEO Alan Jope. The lack of cohesion at the management level is reflected clearly in the words of Terry Smith, founder and chief executive of Fundsmith and the 13th largest investor in Unilever, who described the failed acquisition as a “near death experience”.

Later, Smith also urged the company publicly to focus on the operating performance of its existing business instead of setting itself up for a shopping spree. Nonetheless, the company was set “in play” as they like to say on Wall St. and that’s when Nelson Peltz took a position in Unilever over the weekend. Peltz, head of Trian Partners and an activist investor famously focused on the consumer industry, had made a big splash through his arguably successful investment in P&G, another giant comparable to Unilever under many aspects.

Pelt’s “incursion”, as it is being labeled by most media outlets, is part of the long chain of activists and PE funds that have been actively seizing opportunities over the recent years at unprecedented levels. A company like Unilever is very attractive to any such investor as it is made of several divisions and lines of businesses, which represent greater opportunities of spin-offs of underperforming divisions, which ultimately translate into more shareholders value.

This supposed change we’ll see is also highly anticipated because of the fact that the largest investors at Unilever are represented by organizations like BlackRock and Vanguard. The latter invest through passive funds which basically implies that they can’t sell out of the poorly performing stocks (“ownerless corporations” phenomena) becoming more prone to cheering for activist investors such as Peltz in hopes of improvement.

As it was arguably expected, Unilever rose by more than over 6% and within days of Peltz’ investment, Unilever shifted its focus to making all efforts possible that could lead to a better bottom line. The plan to cut thousands of management jobs the company has famously been in debate for recently, is expected to be only one of the several measures management will have to take in order to restore faith in the company.

It’s very likely that Unilever's “soap opera” wouldn’t have made such big headlines in case activist investors hadn’t shown interest in it. Indeed, this class of investors has always been labeled as the most controversial one on Wall St. However, it’s really hard to be able to distinguish them as “good” or “bad'' because of how different their investments and motives have been over the years. On one hand, the negative perception is perfectly encapsulated by the words of Kai Liekefett, partner at Sidley Austin, who famously said: “Activist investors are really just excel spreadsheet artists. They don’t really always know better than the boards.”

On the other hand, it is undeniable that America wouldn’t have been able to reach its corporate supremacy without the rise of such investors. Let us think for example about the case of MBIA and Bill Ackman, where the latter alarmed the regulators at the top of his lungs about the insurance and derivatives market’s risks long before GFC, or the case of Ebay and Carl Icahn, where the latter divided the company in 2 units, eBay and Paypal, unlocking previously undiscovered shareholder value.

Why they cut afterwards 1500 management jobs

Unilever plans to slash a big chunk of management jobs as part of a push strategy to boost sales growth across the company, which has been under increasing investor pressure.

The company, which employs 149,000 people, unveiled in January a new operational model in order to boost growth. According to one person briefed on the situation, the plan will result in the elimination of thousands of management positions. Unilever was unavailable for comment.

The chief executive Alan Jope, has struggled for months to resurrect sales growth after the company missed the profit margin projections.

GSK's consumer health business was a target for Jope, but Unilever's £50 billion offer was rejected as too low by GSK, angering shareholders and causing the company to drop its interest.

Unilever’s large shareholder Terry Smith felt somehow “relieved” that the GSK deal was not closed and said that management should either focus on enhancing the company's core business or resign immediately. He had previously said that Unilever had "lost the plot," accusing the company's management of prioritizing sustainability over financial results.

Unilever quickly published a strategy update on 17th January, promising to boost its health, beauty, and hygiene division while selling slower-growing operations as the controversy grew.

Furthermore, Unilever announced in its strategy that it would be restructured around five areas: beauty and wellbeing, personal care, home care, nutrition, and ice cream. Its 400-plus brands were currently divided into three categories: beauty & personal care, meals & refreshment, and home care. The restructuring will separate the food industry into two divisions, allowing for a partial sale and each company group will be solely responsible for its own worldwide strategy, growth, and profit.

Jope stated that the new organizational architecture was established over the last year and is geared to maintain the step-up in business' performance. Moving to five category-focused business groups will allow the company to be more responsive to consumer and channel trends while maintaining crystal-clear delivery accountability. The main priority of Unilever is growth, and these changes according to the chief executive will help to achieve this goal.

Unilever has made several new leadership appointments. The chief operating officer, Nitin Paranjpe, has been promoted to chief transformation officer and chief people officer.

A senior investment and markets analyst declared that the management team certainly wants to demonstrate that they are setting a new baseline before starting on another buying spree, considering how negatively the proposal was greeted by customers and investors

Customer loyalty is a valuable asset for Unilever, and the company has been attempting to establish a volume-driven business. However, if the cost of living continues to rise, pricier products may struggle to sell, hence, greater clarity about the next strategy the company is willing to adopt is required immediately.

Written by Leopold Plattner, Arshdeep Sing and Guglielmo Palmieri

In any case, the GSK management was planning to spin-off the business in mid-2022 after pressure from several shareholders, including the US hedge fund Elliott Management. The knock-out argument for a spin-off is that it would be tax-free. Selling the unit would likely reduce the net profit for GSK and other shareholders due to a significant tax-bill. However, this could potentially be mitigated and a demerger from this size would be expected to take longer since regulators would overview and review the transaction.

As financial advisors served Deutsche Bank and Centerview Partners towards Unilever and Goldman Sachs towards GSK.

The role of (activist) investors after the failed M&A transaction

The £50bn failed bid raised several questions about the company’s strategy under the leadership of CEO Alan Jope. The lack of cohesion at the management level is reflected clearly in the words of Terry Smith, founder and chief executive of Fundsmith and the 13th largest investor in Unilever, who described the failed acquisition as a “near death experience”.

Later, Smith also urged the company publicly to focus on the operating performance of its existing business instead of setting itself up for a shopping spree. Nonetheless, the company was set “in play” as they like to say on Wall St. and that’s when Nelson Peltz took a position in Unilever over the weekend. Peltz, head of Trian Partners and an activist investor famously focused on the consumer industry, had made a big splash through his arguably successful investment in P&G, another giant comparable to Unilever under many aspects.

Pelt’s “incursion”, as it is being labeled by most media outlets, is part of the long chain of activists and PE funds that have been actively seizing opportunities over the recent years at unprecedented levels. A company like Unilever is very attractive to any such investor as it is made of several divisions and lines of businesses, which represent greater opportunities of spin-offs of underperforming divisions, which ultimately translate into more shareholders value.

This supposed change we’ll see is also highly anticipated because of the fact that the largest investors at Unilever are represented by organizations like BlackRock and Vanguard. The latter invest through passive funds which basically implies that they can’t sell out of the poorly performing stocks (“ownerless corporations” phenomena) becoming more prone to cheering for activist investors such as Peltz in hopes of improvement.

As it was arguably expected, Unilever rose by more than over 6% and within days of Peltz’ investment, Unilever shifted its focus to making all efforts possible that could lead to a better bottom line. The plan to cut thousands of management jobs the company has famously been in debate for recently, is expected to be only one of the several measures management will have to take in order to restore faith in the company.

It’s very likely that Unilever's “soap opera” wouldn’t have made such big headlines in case activist investors hadn’t shown interest in it. Indeed, this class of investors has always been labeled as the most controversial one on Wall St. However, it’s really hard to be able to distinguish them as “good” or “bad'' because of how different their investments and motives have been over the years. On one hand, the negative perception is perfectly encapsulated by the words of Kai Liekefett, partner at Sidley Austin, who famously said: “Activist investors are really just excel spreadsheet artists. They don’t really always know better than the boards.”

On the other hand, it is undeniable that America wouldn’t have been able to reach its corporate supremacy without the rise of such investors. Let us think for example about the case of MBIA and Bill Ackman, where the latter alarmed the regulators at the top of his lungs about the insurance and derivatives market’s risks long before GFC, or the case of Ebay and Carl Icahn, where the latter divided the company in 2 units, eBay and Paypal, unlocking previously undiscovered shareholder value.

Why they cut afterwards 1500 management jobs

Unilever plans to slash a big chunk of management jobs as part of a push strategy to boost sales growth across the company, which has been under increasing investor pressure.

The company, which employs 149,000 people, unveiled in January a new operational model in order to boost growth. According to one person briefed on the situation, the plan will result in the elimination of thousands of management positions. Unilever was unavailable for comment.

The chief executive Alan Jope, has struggled for months to resurrect sales growth after the company missed the profit margin projections.

GSK's consumer health business was a target for Jope, but Unilever's £50 billion offer was rejected as too low by GSK, angering shareholders and causing the company to drop its interest.

Unilever’s large shareholder Terry Smith felt somehow “relieved” that the GSK deal was not closed and said that management should either focus on enhancing the company's core business or resign immediately. He had previously said that Unilever had "lost the plot," accusing the company's management of prioritizing sustainability over financial results.

Unilever quickly published a strategy update on 17th January, promising to boost its health, beauty, and hygiene division while selling slower-growing operations as the controversy grew.

Furthermore, Unilever announced in its strategy that it would be restructured around five areas: beauty and wellbeing, personal care, home care, nutrition, and ice cream. Its 400-plus brands were currently divided into three categories: beauty & personal care, meals & refreshment, and home care. The restructuring will separate the food industry into two divisions, allowing for a partial sale and each company group will be solely responsible for its own worldwide strategy, growth, and profit.

Jope stated that the new organizational architecture was established over the last year and is geared to maintain the step-up in business' performance. Moving to five category-focused business groups will allow the company to be more responsive to consumer and channel trends while maintaining crystal-clear delivery accountability. The main priority of Unilever is growth, and these changes according to the chief executive will help to achieve this goal.

Unilever has made several new leadership appointments. The chief operating officer, Nitin Paranjpe, has been promoted to chief transformation officer and chief people officer.

A senior investment and markets analyst declared that the management team certainly wants to demonstrate that they are setting a new baseline before starting on another buying spree, considering how negatively the proposal was greeted by customers and investors

Customer loyalty is a valuable asset for Unilever, and the company has been attempting to establish a volume-driven business. However, if the cost of living continues to rise, pricier products may struggle to sell, hence, greater clarity about the next strategy the company is willing to adopt is required immediately.

Written by Leopold Plattner, Arshdeep Sing and Guglielmo Palmieri