Introduction

In January 2023, the US hit its debt ceiling, which represents its borrowing limit. Since then, the Treasury Department implemented extraordinary measures to avoid an immediate default. The Republican-led House of Representatives passed a debt-ceiling bill on 27th April, in which the debt-limit rise is accompanied by sharp spending cuts. The White House responded that “[the bill] has no chance of becoming law”. While the debate is still on, the inability to lift the debt ceiling will trigger catastrophic consequences for the economy.

In January 2023, the US hit its debt ceiling, which represents its borrowing limit. Since then, the Treasury Department implemented extraordinary measures to avoid an immediate default. The Republican-led House of Representatives passed a debt-ceiling bill on 27th April, in which the debt-limit rise is accompanied by sharp spending cuts. The White House responded that “[the bill] has no chance of becoming law”. While the debate is still on, the inability to lift the debt ceiling will trigger catastrophic consequences for the economy.

Causes of the Debt Ceiling Crisis in the USA

From 2009 onwards, when the US government first had to authorize large sums of spending in order to rehabilitate the economy, the debt has nearly tripled, as Congress has authorized trillions of dollars in public expenditure. Since 2001, the USA has consistently run a budget deficit of $1 tn a year on average, meaning that it has spent significantly more than its revenues from taxes and other sources. The debt limit, also called the “debt ceiling”, was created by the Congress of the USA in 1917, to define the maximum amount of federal debt that the US government could accumulate. Then a wartime measure, it remains an object of great economic and political interest. Like 2011, the year 2023 is shaping up to be a pivotal year for the evolution of the debt ceiling crisis. In January of this year, the total national debt amounted to $31.4 tn. The current debt ceiling is also $31.4 tn.

From 2009 onwards, when the US government first had to authorize large sums of spending in order to rehabilitate the economy, the debt has nearly tripled, as Congress has authorized trillions of dollars in public expenditure. Since 2001, the USA has consistently run a budget deficit of $1 tn a year on average, meaning that it has spent significantly more than its revenues from taxes and other sources. The debt limit, also called the “debt ceiling”, was created by the Congress of the USA in 1917, to define the maximum amount of federal debt that the US government could accumulate. Then a wartime measure, it remains an object of great economic and political interest. Like 2011, the year 2023 is shaping up to be a pivotal year for the evolution of the debt ceiling crisis. In January of this year, the total national debt amounted to $31.4 tn. The current debt ceiling is also $31.4 tn.

Theoretically, the debt ceiling was meant to provide debt and budget accountability. Judging by the unfaltering growth of the budget deficit, however, it is evident that the former are not being aptly provided. The reason for this is the fact that raising the debt ceiling has become an almost routine response to large budget deficits. Furthermore, the idea of having a debt ceiling means that the legislature is no longer tasked with approving each borrowing plan – meaning that there is less rigorous and conscious reflection, as well as an inconsistent monitoring of the situation. In the past 62 years, the ceiling has been raised a total of 78 times, and, since 2013, even suspended altogether on seven separate occasions – to avoid the consequential scenario of a default on government debt.

The procedure is standard: the Treasury Department can “no longer pay” the government’s bills, and Congress votes, sometimes even unanimously, to raise the debt ceiling. Political polarization is increasing the occurrence of deadlocks between Republicans and Democrats when it comes to raising the ceiling, meaning that, in the past few years, US debt has been rising at a faster rate than the ceiling, and, in 2011 for instance, the ceiling was raised just two days before it was predicted that the Treasury would exhaust all of its resources – leading to a historical novelty: the downgrade of the country’s creditworthiness. Now, just like in 2010/2011, the Republican Party has control of the House of Representatives. Unfaltering in their resolve to push spending cuts and refuse to increase the debt ceiling, the prospect of a default on sovereign debt appears dangerously close.

The Treasury often resorts to its trademark extraordinary measures in order to prevent a default: that is, the Treasury further indents itself by delaying payments to the retirement accounts of federal employees. Critics refer to such measures as legal gimmicks that have a rapidly approaching expiry date. There are two ways out, and neither of them is particularly easy to implement. The ideal case would be the creation of a budget surplus, or at least the closing of the deficit, however, the disparity would require a huge slash in public spending or a dramatic increase in taxation, both of which are politically contentious actions. Another would be to default on government debt altogether, which would have “catastrophic” consequences. This would downgrade the US’s credit rating, pushing yield rates up and increasing uncertainty, which would translate into an increase in interest rates in the US and globally, and this may have highly recessionary characteristics. As the political landscape gets more and more charged, the threat of default becomes increasingly more concrete. It is evident that the debt ceiling cannot simply continue to be moved like in a game of reverse limbo, because debt cannot be allowed to simply accumulate to no end. This is the essence of the debt ceiling crisis, which is, in its purest form, a crisis of debt accountability.

The procedure is standard: the Treasury Department can “no longer pay” the government’s bills, and Congress votes, sometimes even unanimously, to raise the debt ceiling. Political polarization is increasing the occurrence of deadlocks between Republicans and Democrats when it comes to raising the ceiling, meaning that, in the past few years, US debt has been rising at a faster rate than the ceiling, and, in 2011 for instance, the ceiling was raised just two days before it was predicted that the Treasury would exhaust all of its resources – leading to a historical novelty: the downgrade of the country’s creditworthiness. Now, just like in 2010/2011, the Republican Party has control of the House of Representatives. Unfaltering in their resolve to push spending cuts and refuse to increase the debt ceiling, the prospect of a default on sovereign debt appears dangerously close.

The Treasury often resorts to its trademark extraordinary measures in order to prevent a default: that is, the Treasury further indents itself by delaying payments to the retirement accounts of federal employees. Critics refer to such measures as legal gimmicks that have a rapidly approaching expiry date. There are two ways out, and neither of them is particularly easy to implement. The ideal case would be the creation of a budget surplus, or at least the closing of the deficit, however, the disparity would require a huge slash in public spending or a dramatic increase in taxation, both of which are politically contentious actions. Another would be to default on government debt altogether, which would have “catastrophic” consequences. This would downgrade the US’s credit rating, pushing yield rates up and increasing uncertainty, which would translate into an increase in interest rates in the US and globally, and this may have highly recessionary characteristics. As the political landscape gets more and more charged, the threat of default becomes increasingly more concrete. It is evident that the debt ceiling cannot simply continue to be moved like in a game of reverse limbo, because debt cannot be allowed to simply accumulate to no end. This is the essence of the debt ceiling crisis, which is, in its purest form, a crisis of debt accountability.

Political Debate: the Different Views of Republicans and Democrats

A new drama over the debt ceiling is unfolding in 2023, with Congressional Republicans insisting on spending cuts before backing a debt ceiling hike, while President Biden wants to raise the limit without any conditions to avoid harming the economy. Although debates over the debt ceiling have been ongoing since the 1950s, both parties have used the issue to accuse the other of fiscal irresponsibility. With the country reaching the debt ceiling last month and the Treasury only able to use extraordinary measures to pay bills until early June, there is mounting uncertainty whether the 2023 episode will be worse than the 2011 one that was mentioned before.

The new Republican majority in the House is pushing for a spending slowdown and is steadfast in its determination not to back down. They attribute the rise in food and gasoline prices and the growing national debt to what they consider to be excessive federal spending. Despite the White House's insistence on passing a clean debt ceiling increase, which the Republicans reject, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy leads the charge. There are no indications that this situation will ease in the run-up to the summer deadline for action.

Republicans, having as a goal to shrink Washington, have promised to use the fast-approaching deadline to extract fiscal changes from the White House, many of which target President Biden’s signature economic priorities. In particular, the far-right Freedom Caucus called for clawing back nearly $400 bn to boost clean energy and combat pollution in the Inflation Reduction Act, for example, and an end to the President’s student-loan forgiveness plan, which is awaiting a Supreme Court ruling. They also targeted the roughly $80 bn recently approved to help the IRS pursue tax cheats, arguing it empowers the government to target innocent Americans. That move could add to the deficit, however, since it could prevent Washington from collecting the money it is owed.

The demands made by the Republicans were a direct challenge to President Biden, who has consistently promised not to negotiate the country's credit with them. In early March, speaking at the White House, the president criticized the GOP's latest requests, stating that it revealed their "value set". He also anticipated that the impacts would disproportionately affect police officers, firefighters, and the nation's healthcare.

The resolution of the debt ceiling conflict depends on how the current political environment shapes the debate, as a Democratic president, a thin Democratic Senate majority, and a newly elected Republican House majority work together. However, this environment differs from that of 2011 in several critical ways. Firstly, the GOP has a significantly narrower majority in the House than it did 12 years ago. Additionally, the party is less united behind Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who had to make concessions to the right flank of his party to secure the speakership after 15 rounds of balloting, than it was under then-Speaker John Boehner.

McCarthy's limited hold over his caucus and the narrow majority could impede his ability to reach a compromise with President Biden. On the other hand, the weaker-than-anticipated midterm showing for the Republicans might cause some in the GOP to be hesitant about engaging in an all-out struggle – the opposite of what happened in 2011, when the Republicans felt emboldened by a strong midterm performance and believed they had a mandate to challenge former President Barack Obama.

In any case, it is paramount that the two parties agree on the terms of the debt ceiling lifting to avoid major consequences in the financial markets and on the economy overall.

A new drama over the debt ceiling is unfolding in 2023, with Congressional Republicans insisting on spending cuts before backing a debt ceiling hike, while President Biden wants to raise the limit without any conditions to avoid harming the economy. Although debates over the debt ceiling have been ongoing since the 1950s, both parties have used the issue to accuse the other of fiscal irresponsibility. With the country reaching the debt ceiling last month and the Treasury only able to use extraordinary measures to pay bills until early June, there is mounting uncertainty whether the 2023 episode will be worse than the 2011 one that was mentioned before.

The new Republican majority in the House is pushing for a spending slowdown and is steadfast in its determination not to back down. They attribute the rise in food and gasoline prices and the growing national debt to what they consider to be excessive federal spending. Despite the White House's insistence on passing a clean debt ceiling increase, which the Republicans reject, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy leads the charge. There are no indications that this situation will ease in the run-up to the summer deadline for action.

Republicans, having as a goal to shrink Washington, have promised to use the fast-approaching deadline to extract fiscal changes from the White House, many of which target President Biden’s signature economic priorities. In particular, the far-right Freedom Caucus called for clawing back nearly $400 bn to boost clean energy and combat pollution in the Inflation Reduction Act, for example, and an end to the President’s student-loan forgiveness plan, which is awaiting a Supreme Court ruling. They also targeted the roughly $80 bn recently approved to help the IRS pursue tax cheats, arguing it empowers the government to target innocent Americans. That move could add to the deficit, however, since it could prevent Washington from collecting the money it is owed.

The demands made by the Republicans were a direct challenge to President Biden, who has consistently promised not to negotiate the country's credit with them. In early March, speaking at the White House, the president criticized the GOP's latest requests, stating that it revealed their "value set". He also anticipated that the impacts would disproportionately affect police officers, firefighters, and the nation's healthcare.

The resolution of the debt ceiling conflict depends on how the current political environment shapes the debate, as a Democratic president, a thin Democratic Senate majority, and a newly elected Republican House majority work together. However, this environment differs from that of 2011 in several critical ways. Firstly, the GOP has a significantly narrower majority in the House than it did 12 years ago. Additionally, the party is less united behind Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who had to make concessions to the right flank of his party to secure the speakership after 15 rounds of balloting, than it was under then-Speaker John Boehner.

McCarthy's limited hold over his caucus and the narrow majority could impede his ability to reach a compromise with President Biden. On the other hand, the weaker-than-anticipated midterm showing for the Republicans might cause some in the GOP to be hesitant about engaging in an all-out struggle – the opposite of what happened in 2011, when the Republicans felt emboldened by a strong midterm performance and believed they had a mandate to challenge former President Barack Obama.

In any case, it is paramount that the two parties agree on the terms of the debt ceiling lifting to avoid major consequences in the financial markets and on the economy overall.

Market Reaction: Impact on Treasuries and Economic Considerations

After analyzing the political debate surrounding the current state of the US government debt, we focus on what could potentially happen if no agreement is reached. First, let us consider the impact on US Treasuries.

Traders expect a final 25 basis point increase at the next Fed meeting, followed by a 75 basis point cut, based on current interest rate futures. The cut is probably due to the markets pricing a tail risk of a recession in the second half of 2023. The Fed’s dot plot chart showed the consensus of FOMC members for a further interest rate hike to plateau at 5.10% for 2023 and then decrease gradually until 2025.

Furthermore, according to the latest unemployment rate data, this figure has decreased by 10 basis points, decreasing the likelihood of a Fed pivot in the upcoming months.

During FOMC minutes, several representatives showed a natural rate of unemployment at 4.4%; this is equivalent to saying that about 2 million people in the U.S. will have to lose their jobs and therefore create risks on the welfare system, which will soon have to cope with a growing number of unemployed.

After analyzing the political debate surrounding the current state of the US government debt, we focus on what could potentially happen if no agreement is reached. First, let us consider the impact on US Treasuries.

Traders expect a final 25 basis point increase at the next Fed meeting, followed by a 75 basis point cut, based on current interest rate futures. The cut is probably due to the markets pricing a tail risk of a recession in the second half of 2023. The Fed’s dot plot chart showed the consensus of FOMC members for a further interest rate hike to plateau at 5.10% for 2023 and then decrease gradually until 2025.

Furthermore, according to the latest unemployment rate data, this figure has decreased by 10 basis points, decreasing the likelihood of a Fed pivot in the upcoming months.

During FOMC minutes, several representatives showed a natural rate of unemployment at 4.4%; this is equivalent to saying that about 2 million people in the U.S. will have to lose their jobs and therefore create risks on the welfare system, which will soon have to cope with a growing number of unemployed.

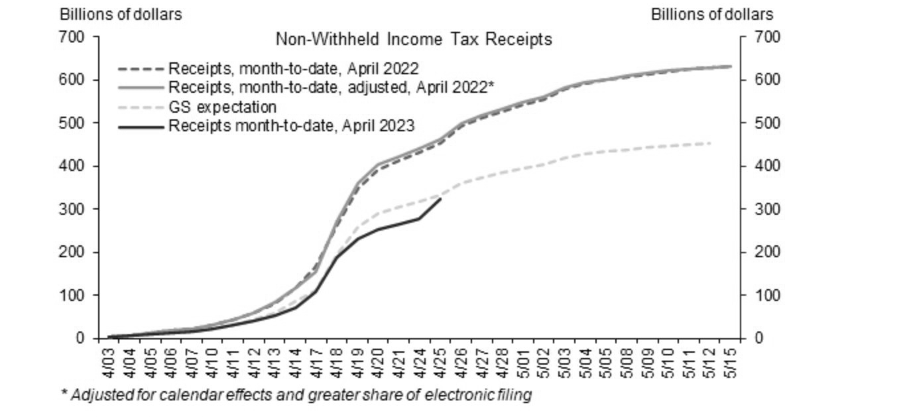

Moreover, the Treasury relies on tax receipts to sustain its current limit, and the more it receives, the longer it can defer additional borrowing. Unfortunately, recent tax collections have fallen below projections, with April receipts lagging behind last year's by 29%, according to Goldman Sachs. This shortfall accelerates the arrival of the so-called X-Day when the Treasury can no longer employ financial maneuvers to hold debt below the limit.

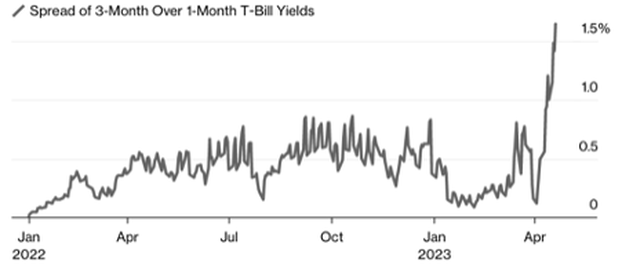

U.S. 3-month bonds have reached yields of around 1.7%, which is equivalent to having an annualized yield of 6.8%. Similarly, assurances of bond defaults have also increased considerably, spilling over into higher yields on credit default swaps.

This statement is only valid if investors are concerned about the possibility that Uncle Sam will be unable to meet his payment obligations in a time frame of one to three months. This is the period when the debt ceiling issue is expected to reach its peak. To further demonstrate that investors view the debt ceiling issue as a significant concern, the chart below represents the credit default swap contract on U.S. government debt. In the past, protecting against a U.S. default was rather cheap, given the improbability of such an event. However, current circumstances have led to increased costs, even exceeding the levels seen after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008 or the infamous debt ceiling dispute in 2011.

This statement is only valid if investors are concerned about the possibility that Uncle Sam will be unable to meet his payment obligations in a time frame of one to three months. This is the period when the debt ceiling issue is expected to reach its peak. To further demonstrate that investors view the debt ceiling issue as a significant concern, the chart below represents the credit default swap contract on U.S. government debt. In the past, protecting against a U.S. default was rather cheap, given the improbability of such an event. However, current circumstances have led to increased costs, even exceeding the levels seen after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008 or the infamous debt ceiling dispute in 2011.

All of these constraints together help strengthen the case for a government not raising the debt ceiling. What, therefore, could be the scenarios should this situation arise?

The economic costs of the US debt limit binding are uncertain but expected to be negative as the short-term effects will depend on the expectations of financial market participants, businesses, and households. However, even if the debt limit were raised quickly, lasting damage would still occur. Financial markets would anticipate disruptions every time the debt limit nears

in the future, and the shock to market confidence would take time to abate.

If the intricacies were to continue, the situation would worsen with mounting legal and political pressures increasing concerns about the negative effects of sharp cuts in federal spending. Worsening expectations regarding a possible default would make significant disruptions in financial markets increasingly probable, resulting in an increase in interest rates on newly- issued Treasuries. If financial markets started to pull back from US Treasuries altogether, the Treasury could have a difficult time finding buyers when it sought to roll over maturing debt.

The disruptions would certainly couple with declines in the price of equities, a loss of business and consumer confidence, and a contraction in access to private credit markets. Such a scenario could trigger a deep recession, and the Treasury would be forced to delay payments of interest or principal on US debt, resulting in a severe disruption to the Treasury securities market, spillovers to other financial markets, and affecting the cost and availability of credit to households and businesses.

This could seriously undermine the reputation of the Treasury market as the safest and most liquid in the world. Consequently, the country could become less attractive to investors, and the cost of borrowing would increase significantly. A worsening of the already serious economic crisis could cause enormous economic and health consequences over time. All US citizens, including federal contractors, employees, state and local agencies, and Social Security beneficiaries, would suffer from delays in payments. Therefore, there is a need for a swift legal challenge to resolve the impasse and prioritize interest payments. Otherwise, the economy

could face severe consequences.

It is difficult to estimate the effect such an event could have on the economy. However, estimates and projections had been made over the past “near-misses”.

The Federal Reserve conducted a simulation in October 2013 to predict the repercussions of a binding debt ceiling for one month, during which the Treasury would continue to pay all interest. The Fed economists estimated that this scenario would cause 10-year Treasury yields to increase by 80 basis points, stock prices to decline by 30%, the dollar to lose 10% of its value, and a decrease in household and business confidence, although these effects would subside over two years. According to their findings, these financial conditions would lead to a two-quarter recession, resulting in a 1.25% increase in the unemployment rate for the following

two years, equating to a loss of 2 million jobs in 2022 and 2.7 million jobs in 2023.

In 2013, Macroeconomic Advisers also conducted a similar exercise, examining the economic costs of two scenarios, one lasting only a brief period, while the other persisting for two months. Even in the case where the impasse was resolved quickly, the economic consequences were significant, with a mild recession and a loss of 2.5 million jobs that returned extremely slowly. The impact was larger and longer-lasting with a two-month impasse, including a deep cut to federal spending in one quarter, offset by a spending surge in the next quarter, eventually resulting in up to 3.1 million job losses in the short term. Even two years after the event, there

remained 2.5 million fewer jobs than there would have been otherwise.

These two simulations provide a useful picture of what might happen if no Debt-Ceiling bill is passed and why investors are paying so much attention to the current political debate.

The economic costs of the US debt limit binding are uncertain but expected to be negative as the short-term effects will depend on the expectations of financial market participants, businesses, and households. However, even if the debt limit were raised quickly, lasting damage would still occur. Financial markets would anticipate disruptions every time the debt limit nears

in the future, and the shock to market confidence would take time to abate.

If the intricacies were to continue, the situation would worsen with mounting legal and political pressures increasing concerns about the negative effects of sharp cuts in federal spending. Worsening expectations regarding a possible default would make significant disruptions in financial markets increasingly probable, resulting in an increase in interest rates on newly- issued Treasuries. If financial markets started to pull back from US Treasuries altogether, the Treasury could have a difficult time finding buyers when it sought to roll over maturing debt.

The disruptions would certainly couple with declines in the price of equities, a loss of business and consumer confidence, and a contraction in access to private credit markets. Such a scenario could trigger a deep recession, and the Treasury would be forced to delay payments of interest or principal on US debt, resulting in a severe disruption to the Treasury securities market, spillovers to other financial markets, and affecting the cost and availability of credit to households and businesses.

This could seriously undermine the reputation of the Treasury market as the safest and most liquid in the world. Consequently, the country could become less attractive to investors, and the cost of borrowing would increase significantly. A worsening of the already serious economic crisis could cause enormous economic and health consequences over time. All US citizens, including federal contractors, employees, state and local agencies, and Social Security beneficiaries, would suffer from delays in payments. Therefore, there is a need for a swift legal challenge to resolve the impasse and prioritize interest payments. Otherwise, the economy

could face severe consequences.

It is difficult to estimate the effect such an event could have on the economy. However, estimates and projections had been made over the past “near-misses”.

The Federal Reserve conducted a simulation in October 2013 to predict the repercussions of a binding debt ceiling for one month, during which the Treasury would continue to pay all interest. The Fed economists estimated that this scenario would cause 10-year Treasury yields to increase by 80 basis points, stock prices to decline by 30%, the dollar to lose 10% of its value, and a decrease in household and business confidence, although these effects would subside over two years. According to their findings, these financial conditions would lead to a two-quarter recession, resulting in a 1.25% increase in the unemployment rate for the following

two years, equating to a loss of 2 million jobs in 2022 and 2.7 million jobs in 2023.

In 2013, Macroeconomic Advisers also conducted a similar exercise, examining the economic costs of two scenarios, one lasting only a brief period, while the other persisting for two months. Even in the case where the impasse was resolved quickly, the economic consequences were significant, with a mild recession and a loss of 2.5 million jobs that returned extremely slowly. The impact was larger and longer-lasting with a two-month impasse, including a deep cut to federal spending in one quarter, offset by a spending surge in the next quarter, eventually resulting in up to 3.1 million job losses in the short term. Even two years after the event, there

remained 2.5 million fewer jobs than there would have been otherwise.

These two simulations provide a useful picture of what might happen if no Debt-Ceiling bill is passed and why investors are paying so much attention to the current political debate.

Written by Giorgio Gusella, Georgia-Alesia Mirica, Alexander Lockhart, and Emanuele Sanvito

Sources

- Associated Press

- Bloomberg

- Brookings InstitutionCouncil of Foreign Relations

- Credit Slips

- Financial Times

- FiveThirtyEight

- Foreign Affairs Magazine

- Wall Street Journal

- Washington Post