Introduction

Recently we have observed a growing interest in sustainable finance and its role in the green transition. Most investors are already familiar with green bonds. They may be less familiar with green Asset-Backed Securities, financial instruments either backed by or used to finance green loans. In this article, we analyze green ABS, with a focus on the recent Toyota green securitization in Italy, and question their current and future ability to both help finance sustainable investments and attract investors.

Understanding Securitization and the Emergence of Green Securitization

Securitization is a process where multiple assets are bundled together to create a single tradable security known as a "compound asset." The return on this compound asset is a weighted average of the returns offered by the individual assets within the bundle. Typically, financial institutions, like banks, engage in securitization to convert illiquid assets, such as loans, into marketable securities. Once created, these compound assets are sold to global capital market investors, providing the originating institution with liquidity. The assets that form the compound asset have different characteristics such as risk or time to maturity, to cater to diverse investor preferences by offering different levels of risk, rewards, and maturities within a single securitized product, the latter is divided into segments based on these characteristics. This process is called tranching, where we differentiate between senior tranches with higher credit ratings and priority in repayment in case of default, and junior tranches carrying higher risk but offering greater potential returns. The appeal of securitization lies in how it is perceived to lower the risk of default, as in a bundle with thousands of assets, one of them defaulting would only slightly affect the bundle, that is assuming that each piece is uncorrelated, and default probability is independently distributed.

Banks in the United States pioneered securitization in the 1970s, primarily focusing on home mortgages. The introduction of mortgage-backed securities allowed banks to provide more mortgage loans, contributing to a housing boom and a surge in house prices. In the 1980s, Wall Street extended the concept to various asset classes, creating a multitude of securities. However, the 2008 recession exposed risks in the market, particularly the deterioration of the quality of underlying assets and a lack of government regulation.

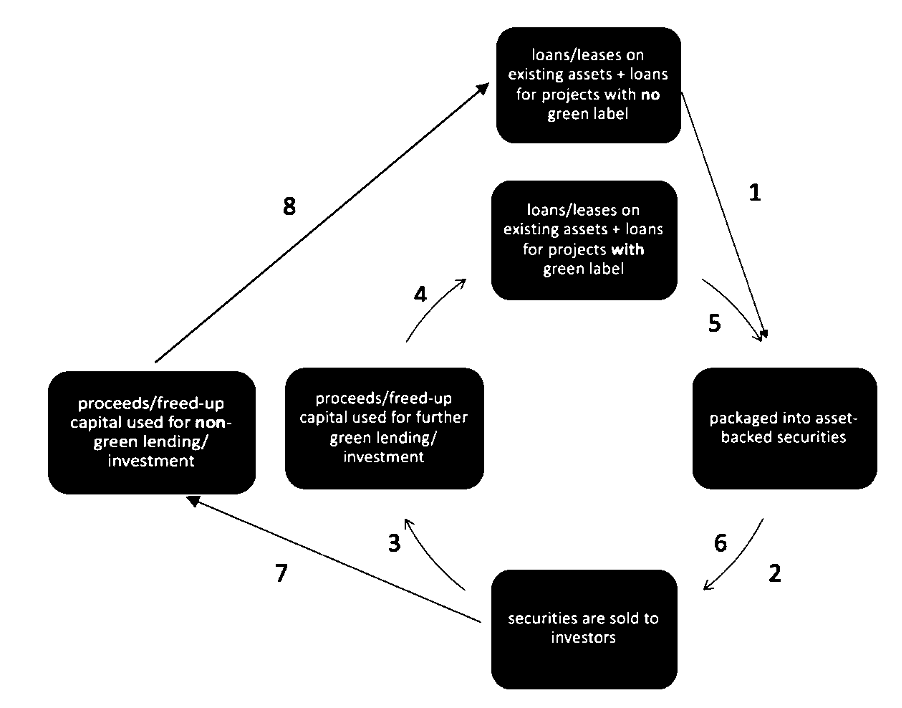

Green securitization is an evolution of the securitization concept, focusing on environmentally sustainable assets. It involves creating financial instruments backed by assets or projects that are environmentally friendly or direct proceeds to fund green initiatives. This approach aligns with the global push for sustainable finance and responsible investing providing individuals with the opportunity to invest in otherwise illiquid markets, promoting liquidity and diversification in the sustainable market.

Banks in the United States pioneered securitization in the 1970s, primarily focusing on home mortgages. The introduction of mortgage-backed securities allowed banks to provide more mortgage loans, contributing to a housing boom and a surge in house prices. In the 1980s, Wall Street extended the concept to various asset classes, creating a multitude of securities. However, the 2008 recession exposed risks in the market, particularly the deterioration of the quality of underlying assets and a lack of government regulation.

Green securitization is an evolution of the securitization concept, focusing on environmentally sustainable assets. It involves creating financial instruments backed by assets or projects that are environmentally friendly or direct proceeds to fund green initiatives. This approach aligns with the global push for sustainable finance and responsible investing providing individuals with the opportunity to invest in otherwise illiquid markets, promoting liquidity and diversification in the sustainable market.

There exist three types of green securities, the first being securitization with Green Collaterals, which involves creating securities backed by green assets, such as electric vehicle loans, solar leases, or loans for environmental projects. The second, Loans for Green Projects, where the loans pooled for securitization are directed toward the development of green projects, contributing to environmental sustainability. Lastly, Note Proceeds for Green Investments, which requires the originator to use proceeds from securitization notes to finance green projects directly or by providing green loans.

In the United States, there is a lack of a consolidated regulatory framework for green securitization. However, the volume of green securitization is substantial, with a focus on Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) models, financing energy efficiency and renewable energy improvements. Major developments include solar energy and electric vehicle-related projects, demonstrating a commitment to sustainable financing frameworks, and contributing to the global effort for a more sustainable future. For instance, in 2022 Mosaic Inc., a fintech firm and financing platform for US residential solar projects, completed its largest-ever solar ABS issuance, raising $382 million.

In the United States, there is a lack of a consolidated regulatory framework for green securitization. However, the volume of green securitization is substantial, with a focus on Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) models, financing energy efficiency and renewable energy improvements. Major developments include solar energy and electric vehicle-related projects, demonstrating a commitment to sustainable financing frameworks, and contributing to the global effort for a more sustainable future. For instance, in 2022 Mosaic Inc., a fintech firm and financing platform for US residential solar projects, completed its largest-ever solar ABS issuance, raising $382 million.

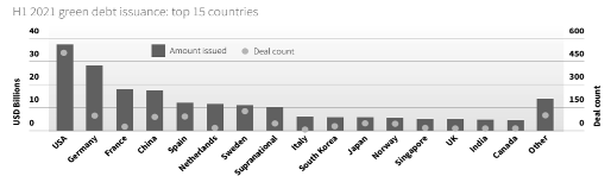

While green bonds have gained traction, green securitization in the European Union remains subdued. Between 2019-2022, green securitization represented only 1.4% of total European green issuance (less than €10bn), contrasting with 8.1% in China (RMB 115bn, €16.1bn) and 32.3% in the United States ($115bn, €105bn). The EU has taken steps to boost green finance, with recent regulation on “European Green Bonds” (EuGB). The proposed use of proceeds framework, applicable to the originator rather than the issuer, aims to encourage the inclusion of green collateral at the originator level, allowing transactions to be designated as “European green bonds”. Toyota’s new green securitization program in Italy highlights the European effort to develop green securitization within the continent.

Case study: Toyota green securitization, Koromo Italy

Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) is a Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer founded in 1937 by Kiichiro Toyoda as a spinoff of Toyota Industries, an automatic loom manufacturer.

In 2000 the TMC conglomerate established the Toyota Financial Service Corporation (TFSC) as a holding company operating in the five regions of Americas Oceania, Europe/Africa, Asia Pacific, Japan, and China. Aiming at reinforcing the competitiveness and profitability of Toyota’s financial business, TFSC is now responsible for assessing the market, developing the strategy, and supporting the local financial services companies to best meet the various needs of Toyota customers.

TMC is concerned with reducing its negative impacts on both the planet and society and to do so, in 2015, the Toyota Environmental Challenge 2050 was announced, involving six highly demanding challenges such as: “reduce CO2emissions from new vehicles by 90%, eliminate CO2 emissions from operations, suppliers, and dealers, protect water resources, support a recycling-based society, and conserve biodiversity among the globe”.

According to the Europe/Africa region, in 1997 Toyota Financial Service Italia (TFSI) was founded as a branch of TFSUK, becoming a legal entity in Italy only in 2019.

TFSI operates in the market as a captive entity for the conglomerate offering three types of financial products (loans, leasing, and wholesale factoring) to promote the sales of both Toyota and Lexus.

To pursue the group’s ESG targets, Toyota Italia has formulated a long-term strategy known as ‘Beyond Zero’ to reach zero emissions in the sector.

As a response to the challenge, TFSI promoted in February 2023 the first marketed securitization in the EMEA region: Koromo Italy.

The public securitization transaction comprehends collateral comprised of loans for only alternative fuel vehicles (AFV), giving the possibility to private borrowers to purchase hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and electric-only vehicles.

The ABS deal is backed by a €412 million pool of assets and involves the issuance of two tranches: Class A Notes, offered to investors and rated Aa3 by Moody’s and AA by Fitch, and Junior Notes, retained by TSFI as a form of internal credit enhancement.

Apart from the originator (TSFI) and the issuer (Koromo Italy S.r.l.), the main third parties in the deal have been Citigroup Global Markets Limited, which served as both the sole arranger and the lead manager, and Zenith Service S.p.A. covering the role of master servicer and calculation agent.

The main rating agencies have been Moody’s and Fitch, which reported the nature of AFV as an additional source of risk. Furthermore, PCS verification agent has validated the transaction STS compliance.

Even though Toyota already has an auto green issuance in the United States since 2014, this first deal in the European market represents a major step forward for both the EMEA region, with the expectation that many more green STS deals will be concluded, and the Japanese corporation.

In 2000 the TMC conglomerate established the Toyota Financial Service Corporation (TFSC) as a holding company operating in the five regions of Americas Oceania, Europe/Africa, Asia Pacific, Japan, and China. Aiming at reinforcing the competitiveness and profitability of Toyota’s financial business, TFSC is now responsible for assessing the market, developing the strategy, and supporting the local financial services companies to best meet the various needs of Toyota customers.

TMC is concerned with reducing its negative impacts on both the planet and society and to do so, in 2015, the Toyota Environmental Challenge 2050 was announced, involving six highly demanding challenges such as: “reduce CO2emissions from new vehicles by 90%, eliminate CO2 emissions from operations, suppliers, and dealers, protect water resources, support a recycling-based society, and conserve biodiversity among the globe”.

According to the Europe/Africa region, in 1997 Toyota Financial Service Italia (TFSI) was founded as a branch of TFSUK, becoming a legal entity in Italy only in 2019.

TFSI operates in the market as a captive entity for the conglomerate offering three types of financial products (loans, leasing, and wholesale factoring) to promote the sales of both Toyota and Lexus.

To pursue the group’s ESG targets, Toyota Italia has formulated a long-term strategy known as ‘Beyond Zero’ to reach zero emissions in the sector.

As a response to the challenge, TFSI promoted in February 2023 the first marketed securitization in the EMEA region: Koromo Italy.

The public securitization transaction comprehends collateral comprised of loans for only alternative fuel vehicles (AFV), giving the possibility to private borrowers to purchase hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and electric-only vehicles.

The ABS deal is backed by a €412 million pool of assets and involves the issuance of two tranches: Class A Notes, offered to investors and rated Aa3 by Moody’s and AA by Fitch, and Junior Notes, retained by TSFI as a form of internal credit enhancement.

Apart from the originator (TSFI) and the issuer (Koromo Italy S.r.l.), the main third parties in the deal have been Citigroup Global Markets Limited, which served as both the sole arranger and the lead manager, and Zenith Service S.p.A. covering the role of master servicer and calculation agent.

The main rating agencies have been Moody’s and Fitch, which reported the nature of AFV as an additional source of risk. Furthermore, PCS verification agent has validated the transaction STS compliance.

Even though Toyota already has an auto green issuance in the United States since 2014, this first deal in the European market represents a major step forward for both the EMEA region, with the expectation that many more green STS deals will be concluded, and the Japanese corporation.

Does green securitization work?

As the financial world tries to adapt to the net zero goals championed by policymakers, ESG efforts find themselves under scrutiny, and green securitization is no exception in this case.

The European market displays relatively low demand in the short term and the position of banks as providers of capital for low-carbon investments is well-established. On one hand, this means that there is ample potential for growth within the continent, provided that funding through this type of securitization provides a viable alternative to debt funding on a pragmatic level. According to the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME): “although demand for green securitization bond is still relatively low at present, many institutional investors (…) have increased their commitment to invest in green assets in line with their policy objectives. AFME’s members are also seeing an increasing number of queries and reverse inquiries around green securitizations and believe the market has considerable potential to grow”. Companies can also benefit greatly from reputational advantages.

The concrete benefits of a more diffused use of green ABS can be analyzed through a market-level as well as a bank-level perspective. On a market level, this practice would allow for the aggregation of small green projects into substantial financial instruments, allowing for more comprehensive access to capital markets – at a potentially lower cost. Green ABS would allow investors to balance financial returns with environmental benefits and would allow investors to actively hedge against climate policy risk, which is becoming increasingly concerning nowadays. These instruments have been shown to be attractive to buy-side actors, according to a market study conducted in 2017 by Kidney et al., although it must be mentioned that potential yields are currently inflated because of the lack of rating history. An interesting future prospect concerns the potential of the use of green securities by Central Banks in Green Quantitative Easing schemes. At a bank level, green securitization can be an important diversifying liability and increase lending capacity. However, the lack of information regarding this area is bound to mean extra costs: transactional, legal, and compliance-related, and the liquidity of the green debt market is dubious.

This brings us to the costs and risks of pursuing such projects, which should not be understated. The legal and procedural environment is complicated and ever-evolving in such a new field. On the public sector side, there are numerous regulations, definitions, and standards around public authority certification, as well as an aggregation cost arising from the difficulty of pooling assets with different features – which could come to be attenuated only after interest and supply of such instruments allows for more precise classifications. Another reservation investors have relates to the actual greenness of the securitization, seeing as this term is usually used to refer to green collateral, green proceeds, and green capital securitization. In the second and third cases, it may happen for the proceeds or capital relief to be backed by a pool of non-green assets, not being themselves dependent upon green assets (this can also be called a carbon lock-in). This means that there is room to speculate greenwashing, in which the environmental merits turn out to be ultimately unsubstantiated, while the existing legal basis to counter such occurrences is sparse at best.

For instance, in a separate issuance in 2017, Toyota issued three green asset-backed securities for €4.6bn; however, the portfolios of the assets backing the green securities included oil, gas, automotive, and other “brown” assets. Environmentalists argue that, as it currently operates, green securitization is not an effective policy resulting in new green lending, and that it just “assists the green PR efforts of financial institutions while doing little-to-no good for the environment”. Overall, the absence of a standardized definition, common risk and cash flow assessment methodology, and standardization among green loan contracts stand out as barriers to the development of this area, calling for more regulatory initiatives in order to help uncover the potential of this area. The most balanced conclusion that can be drawn is that this is still a developing field, and, just as it would be premature to condemn it from the start, caution, labor, and time are necessary for the realization of any of the potential benefits described above.

The European market displays relatively low demand in the short term and the position of banks as providers of capital for low-carbon investments is well-established. On one hand, this means that there is ample potential for growth within the continent, provided that funding through this type of securitization provides a viable alternative to debt funding on a pragmatic level. According to the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME): “although demand for green securitization bond is still relatively low at present, many institutional investors (…) have increased their commitment to invest in green assets in line with their policy objectives. AFME’s members are also seeing an increasing number of queries and reverse inquiries around green securitizations and believe the market has considerable potential to grow”. Companies can also benefit greatly from reputational advantages.

The concrete benefits of a more diffused use of green ABS can be analyzed through a market-level as well as a bank-level perspective. On a market level, this practice would allow for the aggregation of small green projects into substantial financial instruments, allowing for more comprehensive access to capital markets – at a potentially lower cost. Green ABS would allow investors to balance financial returns with environmental benefits and would allow investors to actively hedge against climate policy risk, which is becoming increasingly concerning nowadays. These instruments have been shown to be attractive to buy-side actors, according to a market study conducted in 2017 by Kidney et al., although it must be mentioned that potential yields are currently inflated because of the lack of rating history. An interesting future prospect concerns the potential of the use of green securities by Central Banks in Green Quantitative Easing schemes. At a bank level, green securitization can be an important diversifying liability and increase lending capacity. However, the lack of information regarding this area is bound to mean extra costs: transactional, legal, and compliance-related, and the liquidity of the green debt market is dubious.

This brings us to the costs and risks of pursuing such projects, which should not be understated. The legal and procedural environment is complicated and ever-evolving in such a new field. On the public sector side, there are numerous regulations, definitions, and standards around public authority certification, as well as an aggregation cost arising from the difficulty of pooling assets with different features – which could come to be attenuated only after interest and supply of such instruments allows for more precise classifications. Another reservation investors have relates to the actual greenness of the securitization, seeing as this term is usually used to refer to green collateral, green proceeds, and green capital securitization. In the second and third cases, it may happen for the proceeds or capital relief to be backed by a pool of non-green assets, not being themselves dependent upon green assets (this can also be called a carbon lock-in). This means that there is room to speculate greenwashing, in which the environmental merits turn out to be ultimately unsubstantiated, while the existing legal basis to counter such occurrences is sparse at best.

For instance, in a separate issuance in 2017, Toyota issued three green asset-backed securities for €4.6bn; however, the portfolios of the assets backing the green securities included oil, gas, automotive, and other “brown” assets. Environmentalists argue that, as it currently operates, green securitization is not an effective policy resulting in new green lending, and that it just “assists the green PR efforts of financial institutions while doing little-to-no good for the environment”. Overall, the absence of a standardized definition, common risk and cash flow assessment methodology, and standardization among green loan contracts stand out as barriers to the development of this area, calling for more regulatory initiatives in order to help uncover the potential of this area. The most balanced conclusion that can be drawn is that this is still a developing field, and, just as it would be premature to condemn it from the start, caution, labor, and time are necessary for the realization of any of the potential benefits described above.

Future outlooks of green securitization

To assess the future popularity and potential volume of green asset-backed securities, we need to examine the supply and demand side. On the supply side, there need to be enough securitizable assets with similar characteristics to be able to be bundled into ABSs. On the demand side, the question is whether investors will have an appetite for these securities which would fuel their creations.

Supply side

The extent to which green securitization will be a predominant financing method strongly depends on the growth of the underlying green assets and as a result of green public policy and technological progress. Given the current trends in green technology, until 2030 the bulk of such securities is likely to be written on three main consumer assets, mortgage loans on energy-efficient properties, mortgages for green renovation of existing properties, and electric vehicle loans.

Green residential mortgages have been around for years. For example, the first European green residential mortgage-based securities (RMBS) issuance took place back in 2016. Its volumes have not been significant so far. Green RMBS are also not likely to grow in the near future (until 2030) as recent EU legislature established high technical screening criteria for real estate projects to be eligible for green securitization. The current aggregate value of green RMBS in large European countries amounted to around EUR 125 billion in 2022, and their level is projected to stay constant. In order to achieve significant growth in this field, regulatory change and institutional willingness to identify and certify eligible assets are required. Though green renovation of properties is likely to be a growing segment, many households will likely self-fund such renovations, therefore the annual EUR 75 billion funding requirement for such projects in dominant European markets may only be partially addressed with securitized products.

Electric car financing is also a promising market for green securitized loans. Current green asset-backed securities on car loans have mostly hybrid electric vehicles (HEV) as underlying loan assets, constituting 98% of underlying loans in the case of Koromo Italy. As electric vehicle technology progresses and EVs become more affordable, an increase in both the quantity of EV car loans and the quality (less polluting technologies, higher proportion of BEVs) is expected. Furthermore, with the advancement of battery technology, and increasing market penetration of electric vehicles, the secondhand market of EVs is also expected to grow rapidly providing an additional asset pool for green ABSs. Until 2030 the estimated securitizable financing from new and used EVs is EUR 80 and 30 billion respectively.

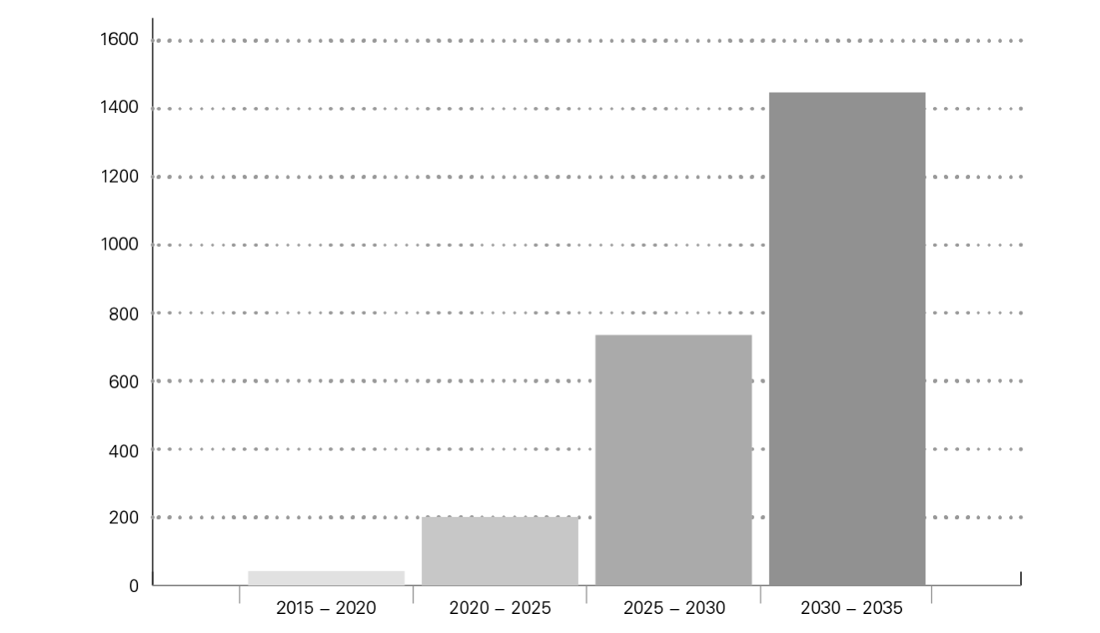

In general, green ABS prospects remain positive, with forecasted annual issuances of $280bn by 2035 in the baseline scenario and the potential to reach $380bn in the best-case scenario.

Supply side

The extent to which green securitization will be a predominant financing method strongly depends on the growth of the underlying green assets and as a result of green public policy and technological progress. Given the current trends in green technology, until 2030 the bulk of such securities is likely to be written on three main consumer assets, mortgage loans on energy-efficient properties, mortgages for green renovation of existing properties, and electric vehicle loans.

Green residential mortgages have been around for years. For example, the first European green residential mortgage-based securities (RMBS) issuance took place back in 2016. Its volumes have not been significant so far. Green RMBS are also not likely to grow in the near future (until 2030) as recent EU legislature established high technical screening criteria for real estate projects to be eligible for green securitization. The current aggregate value of green RMBS in large European countries amounted to around EUR 125 billion in 2022, and their level is projected to stay constant. In order to achieve significant growth in this field, regulatory change and institutional willingness to identify and certify eligible assets are required. Though green renovation of properties is likely to be a growing segment, many households will likely self-fund such renovations, therefore the annual EUR 75 billion funding requirement for such projects in dominant European markets may only be partially addressed with securitized products.

Electric car financing is also a promising market for green securitized loans. Current green asset-backed securities on car loans have mostly hybrid electric vehicles (HEV) as underlying loan assets, constituting 98% of underlying loans in the case of Koromo Italy. As electric vehicle technology progresses and EVs become more affordable, an increase in both the quantity of EV car loans and the quality (less polluting technologies, higher proportion of BEVs) is expected. Furthermore, with the advancement of battery technology, and increasing market penetration of electric vehicles, the secondhand market of EVs is also expected to grow rapidly providing an additional asset pool for green ABSs. Until 2030 the estimated securitizable financing from new and used EVs is EUR 80 and 30 billion respectively.

In general, green ABS prospects remain positive, with forecasted annual issuances of $280bn by 2035 in the baseline scenario and the potential to reach $380bn in the best-case scenario.

Demand side

Green asset-backed securities are unlikely to experience future growth if there is not a clear demand from investors for such instruments. The demand for green securities currently exists, and sustainability is a factor that investors consider when constructing their investment portfolios. This is especially true for younger investors, as there has been shown to be a large gap in attitude towards ESG principles among generations. 80% of Millennials and Generation Z investors believe their investment firms should keep environmental issues in mind when investing, while the same metric for Gen X investors is 67%, and for baby boomer investors it is only 35%. As more people from the younger generations become part of the workforce and start investing their disposable income, demand for green assets will likely grow.

Currently, the gap between demand and supply makes green assets overpriced compared with equivalent securities and incentivizes the phenomenon of greenwashing. As supply grows and meets investors' demand, green securities may become the new standard and will be fairly priced by the market.

Green asset-backed securities are unlikely to experience future growth if there is not a clear demand from investors for such instruments. The demand for green securities currently exists, and sustainability is a factor that investors consider when constructing their investment portfolios. This is especially true for younger investors, as there has been shown to be a large gap in attitude towards ESG principles among generations. 80% of Millennials and Generation Z investors believe their investment firms should keep environmental issues in mind when investing, while the same metric for Gen X investors is 67%, and for baby boomer investors it is only 35%. As more people from the younger generations become part of the workforce and start investing their disposable income, demand for green assets will likely grow.

Currently, the gap between demand and supply makes green assets overpriced compared with equivalent securities and incentivizes the phenomenon of greenwashing. As supply grows and meets investors' demand, green securities may become the new standard and will be fairly priced by the market.

Conclusion

Green securitization has an undeniable potential to become a critical instrument in sustainable finance. However, it is clear that the legal and administrative infrastructure around it will have to undergo extensive changes before it becomes a widespread practice. The Koromo project represents an important step in the move toward greater sustainability within the EMEA economic space and its future performance is likely to act as a signal to companies and investors alike, potentially opening a new chapter in the area’s sustainable evolution.

By Francesca Dini, Mate Mangoff, Georgia-Alesia Mirica, Maxime Vallot

Sources

- AFME

- Banca d’Italia

- Climate Bonds Initiative

- European University Institute

- Fitch

- GlobalCapital

- OECD

- Positive Money

- Stanford GSB

- Societé Generale

- Toyota Financial Services

- White & Case LLP