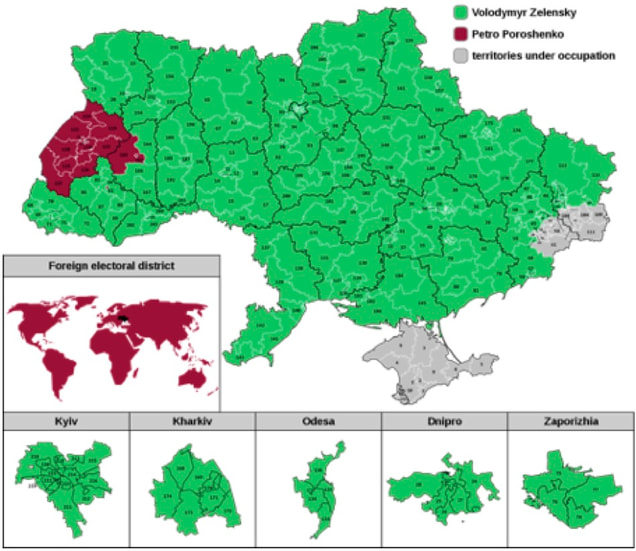

On April 21st 2019, an interesting and important election took place just outside the Eastern borders of the European Union. The 2019 Ukrainian presidential election, which has been well covered by Western media, marks a new chapter in Ukrainian politics. Almost six years after the Euromaidan protests, which left hundreds dead and many more injured, the Ukrainian electorate voted for Volodymyr Zelensky, a comedian with no political experience. After none of the candidates received an absolute majority of the vote in the first round, Zelensky received more than 73% of all votes in the second round, defeating the office-holder Petro Poroshenko by a landslide victory.

Since Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and separatists still occupy parts of Eastern Ukraine including Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast, roughly 12% of the 34,5 million eligible voters were not able to participate in the elections. While the voter turnout of 68% was slightly lower than in previous presidential elections, a record number of international and non-governmental organizations was registered as observers in order to monitor the elections in the war-shattered country. Experts agree that free elections were one of the major achievements of Petro Poroshenko, who governed the country since early presidential elections took place after the former president Viktor Yanukovych fled to Russia in early 2014. During a gathering with supporters the day after his defeat, Mr Poroshenko told the crowd that “In five years, we have accomplished more than anyone in the previous 25 years. Our biggest victories are still to come.” He went on congratulating Mr Zelensky for his victory, while days before he told journalists his contender was unfit for office. Mr Poroshenko was admired and well regarded in Western European capitals for pushing through necessary reforms to secure a heavy IMF package and enable a free-trade deal as well as visa-free travels for his citizens.

Those austerity measures that helped Petro Poroshenko securing this deal led to substantially higher utility bills and were rejected by much of the electorate. Mr Zelensky took advantage of voter anger against Petro Poroshenko, accusing the oligarch and confectionary billionaire of corruption and failure to lift living standards. Essentially, his campaign was directed against the Ukrainian political establishment, to which Mr Poroshenko belongs. However, Mr Zelensky, who ran an unorthodox campaign as an anti-establishment candidate, has pledged to preserve Ukraine’s drive to closer European Union integration and speed up reforms. Little is known about his in-depth plans on how to deal with Russian exertion of influence in Eastern Ukraine and how to boost the economy. After all, he will have to satisfy the electorate by cracking down on corruption and raising living standards. After a heavy recession following the protests and government turmoil of 2014, Ukraine saw a steady 2 – 3 per cent growth during the first years of Petro Poroshenko’s presidency. Western diplomats regard the transition process in Ukraine as unique, despite its difficult circumstances in facing military aggression by Russian-backed separatists in the Eastern provinces of the country.

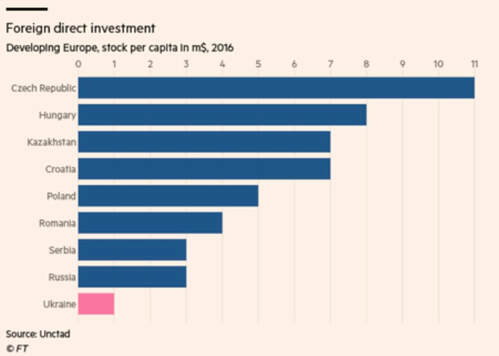

Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, was quick to pledge the EU support to the newly elected leader. Nevertheless, it will be interesting to see how Mr Zelensky handles relationships with international organizations such as the IMF, but also with its direct neighbours and the European Union. In a television show that was produced some years ago, Mr Zelensky, who plays the role of the main character, rips apart the IMF deal. Interestingly, the TV station that hosts Zelensky’s hit show is owned by Ihor Kolomoisky, an oligarch currently living in exile in Geneva and Tel Aviv. Mr Zelensky denies being under the oligarch’s influence. More recently, however, he took a practical approach by giving support to the IMF programme and surrounding himself by reformist advisors. He has yet to prove that he understands the seriousness and comprehensiveness of the job. Many problems remain to be fixed by the new president: an article published by the Financial Times in early 2018 lists the scarcity of affordable funding and low investment as key problems. To reach the potential growth of 6 to 7 per cent, an advisor to the government mentions that FDI should be at about 25% of Ukrainian GDP, a significant increase compared to current levels of 15%. Even on a per capita basis Ukraine falls behind most of the former Soviet countries, with the Czech Republic’s FDI per capita being 11 times higher. Last year, the Central Bank increased the lending rate from 14.5% to 16% to reflect higher inflation in the country. Henceforth, Ukrainian banks are hesitant to give out loans, let alone cheap ones, which hinders firms from investing and growing. Mr Poroshenko made a first step in the right direction by consolidating and strengthening the banking system, but much work remains to be done.

Those austerity measures that helped Petro Poroshenko securing this deal led to substantially higher utility bills and were rejected by much of the electorate. Mr Zelensky took advantage of voter anger against Petro Poroshenko, accusing the oligarch and confectionary billionaire of corruption and failure to lift living standards. Essentially, his campaign was directed against the Ukrainian political establishment, to which Mr Poroshenko belongs. However, Mr Zelensky, who ran an unorthodox campaign as an anti-establishment candidate, has pledged to preserve Ukraine’s drive to closer European Union integration and speed up reforms. Little is known about his in-depth plans on how to deal with Russian exertion of influence in Eastern Ukraine and how to boost the economy. After all, he will have to satisfy the electorate by cracking down on corruption and raising living standards. After a heavy recession following the protests and government turmoil of 2014, Ukraine saw a steady 2 – 3 per cent growth during the first years of Petro Poroshenko’s presidency. Western diplomats regard the transition process in Ukraine as unique, despite its difficult circumstances in facing military aggression by Russian-backed separatists in the Eastern provinces of the country.

Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, was quick to pledge the EU support to the newly elected leader. Nevertheless, it will be interesting to see how Mr Zelensky handles relationships with international organizations such as the IMF, but also with its direct neighbours and the European Union. In a television show that was produced some years ago, Mr Zelensky, who plays the role of the main character, rips apart the IMF deal. Interestingly, the TV station that hosts Zelensky’s hit show is owned by Ihor Kolomoisky, an oligarch currently living in exile in Geneva and Tel Aviv. Mr Zelensky denies being under the oligarch’s influence. More recently, however, he took a practical approach by giving support to the IMF programme and surrounding himself by reformist advisors. He has yet to prove that he understands the seriousness and comprehensiveness of the job. Many problems remain to be fixed by the new president: an article published by the Financial Times in early 2018 lists the scarcity of affordable funding and low investment as key problems. To reach the potential growth of 6 to 7 per cent, an advisor to the government mentions that FDI should be at about 25% of Ukrainian GDP, a significant increase compared to current levels of 15%. Even on a per capita basis Ukraine falls behind most of the former Soviet countries, with the Czech Republic’s FDI per capita being 11 times higher. Last year, the Central Bank increased the lending rate from 14.5% to 16% to reflect higher inflation in the country. Henceforth, Ukrainian banks are hesitant to give out loans, let alone cheap ones, which hinders firms from investing and growing. Mr Poroshenko made a first step in the right direction by consolidating and strengthening the banking system, but much work remains to be done.

Mr Zelensky, a native Russian speaker, already indicated that he is open to peace talks with the Russian president Vladimir Putin. Ending the war would most likely make a national hero out of Mr Zelensky, something his predecessor could not achieve. Furthermore, this would stabilize the countries’ financial markets and lower its funding costs, which are currently at 14.8% for a 10-year Ukrainian government bond. After all, the country risks falling behind Moldova as Europe’s poorest country in per capita terms. Ultimately, the newly elected president will be judged on the basis of the increase in living standards for his electorate. On election day, Mr Zelensky told his supporters: “I will never let you down. While I am not formally president yet, as a citizen of Ukraine I can tell all post-Soviet countries: look at us, everything is possible”, eying at their larger neighbour to the East.

Maximilian Schneider

Maximilian Schneider