IPO frenzy

This year has been widely expected to be a blockbuster year for IPOs and as several startups are entering the public markets. Tech “unicorns” - privately held firms worth over $1bn - are getting the center of the attention.

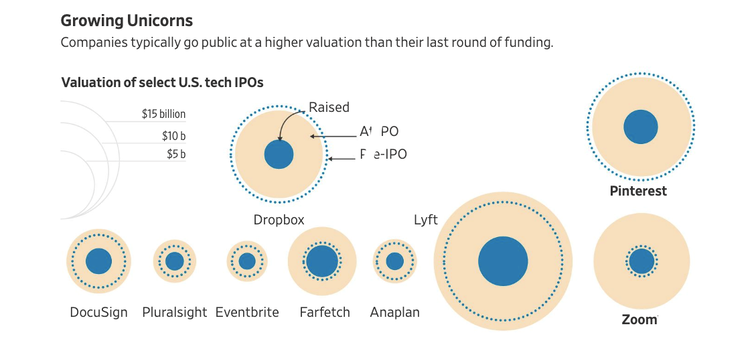

The ride-hailing company Lyft kicked off the wave of tech offerings and beat expectations reaching a $24 billion valuation. It was soon followed by Pinterest and Zoom, respectively valued at $12.6 and $10 billion. And the IPOs in the pipeline look even more appealing: as of this writing, Uber is to seek a valuation as high as $90 billion and the workplace messaging app Slack has unsealed its paperwork to the SEC to be directly listed on the NYSE, with its prospectus indicating a valuation of around $17 billion. Many others, among which Airbnb and the data analytics platform Palantir, have taken steps towards going public in the second half of the year.

All these companies claim that the areas they work in are just a small part of the markets they intend to dominate and that they can guarantee high margins to investors in the foreseeable future. Yet, increasing user numbers and evident revenue growth shown in their IPO filings have not proved enough to convince a part of Wall Street.

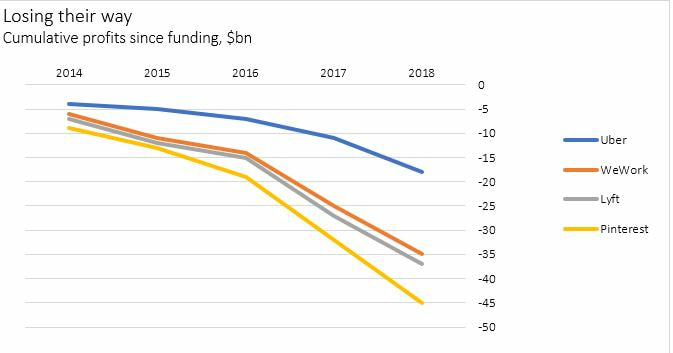

Some valuations have been considered unusually high with respect to the companies’ fundamentals, mainly because in most of the cases these businesses lack one thing: profits. Today, according to Jay Ritter of the University of Florida, 84% of companies pursuing IPOs lack positive figures at the bottom line; the percentage rises to 92% if we consider the class of tech unicorns. To see similar data, we need to go back as far as the peak of the dotcom bubble. Back then, companies promised profits would follow once the companies grew. Nowadays, even if companies grow substantially before going public (see Uber), they are still unable to make profits.

This year has been widely expected to be a blockbuster year for IPOs and as several startups are entering the public markets. Tech “unicorns” - privately held firms worth over $1bn - are getting the center of the attention.

The ride-hailing company Lyft kicked off the wave of tech offerings and beat expectations reaching a $24 billion valuation. It was soon followed by Pinterest and Zoom, respectively valued at $12.6 and $10 billion. And the IPOs in the pipeline look even more appealing: as of this writing, Uber is to seek a valuation as high as $90 billion and the workplace messaging app Slack has unsealed its paperwork to the SEC to be directly listed on the NYSE, with its prospectus indicating a valuation of around $17 billion. Many others, among which Airbnb and the data analytics platform Palantir, have taken steps towards going public in the second half of the year.

All these companies claim that the areas they work in are just a small part of the markets they intend to dominate and that they can guarantee high margins to investors in the foreseeable future. Yet, increasing user numbers and evident revenue growth shown in their IPO filings have not proved enough to convince a part of Wall Street.

Some valuations have been considered unusually high with respect to the companies’ fundamentals, mainly because in most of the cases these businesses lack one thing: profits. Today, according to Jay Ritter of the University of Florida, 84% of companies pursuing IPOs lack positive figures at the bottom line; the percentage rises to 92% if we consider the class of tech unicorns. To see similar data, we need to go back as far as the peak of the dotcom bubble. Back then, companies promised profits would follow once the companies grew. Nowadays, even if companies grow substantially before going public (see Uber), they are still unable to make profits.

Overvaluation does not necessarily mean that the coming wave of IPOs will not go on, but it does suggest rough times ahead. Indeed, large first-day pops have signaled investor confidence in tech initial offerings, but Lyft’s stock performance, down 14% to its debut price as of today, has casted a pall over the market.

The first to follow the highly-anticipated public offering of the ride-hailing company on the Nasdaq was the cloud videoconferencing service Zoom; on the same day, Pinterest went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

Pinterest

The venture capital darling, founded in 2010 and known for its loyal fan base that posts food home decor and wedding collages, launched its “down round” IPO earlier this month. It raised 1.4bn by selling 75m shares at $19 - above the range earlier indicated, but still 12 per cent below the price it achieved in a private fundraising two years ago. It joined Dropbox in the group of tech companies entering the public markets with a valuation lower than their last private share sale.

The first to follow the highly-anticipated public offering of the ride-hailing company on the Nasdaq was the cloud videoconferencing service Zoom; on the same day, Pinterest went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

The venture capital darling, founded in 2010 and known for its loyal fan base that posts food home decor and wedding collages, launched its “down round” IPO earlier this month. It raised 1.4bn by selling 75m shares at $19 - above the range earlier indicated, but still 12 per cent below the price it achieved in a private fundraising two years ago. It joined Dropbox in the group of tech companies entering the public markets with a valuation lower than their last private share sale.

The offering, led by J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs and Allen & Company, valued the company at around $12.6bn, including restricted stock units issued to its employees and options. At issuance, the venture capital investor Bessemer was the largest single investor, with a 13% stake. Ben Silberman, co-founder and chief executive officer, was left with a stake worth around $981m. Other big holders included venture capitalists FirstMark and Andreessen Horowitz, as well as co-founder Paul Sciarra, holding stakes worth more than $800m.

The balance between public ownership and maintaining founder control has become a symbol of tech IPOs. Indeed, the scrapbooking site followed Lyft’s example and issued two classes of shares with different voting powers. In particular, while early backers and the founders have 20 votes per share (Class B), ordinary shareholders have just one vote per share (Class A). Supporters of dual-class structures sustain this allows founders to focus on longer-term goals and protect them from attacks by activist investors.

As clear from the prospectus filed to the SEC, the photo sharing platform views itself as the place “where more than 250 million people around the world go to get inspiration for their lives”- namely a visual search company, rather than a social network. Nonetheless, it cited Snap, Facebook and Twitter as its greatest competitors in its S-1 paperwork. And the reason behind this choice is quite obvious once we consider the main source of revenues for the image sharing platform: advertising.

Together with the most used cost-per-click (CPC) and cost per thousand (CPM) advertising model, Pinterest has created a so-called “pin ad strategy”, which charges advertisers on the engagement or action. That enables the advertiser to pay only when existing users engage with a promoted pin, eventually increasing the potential return on investment.

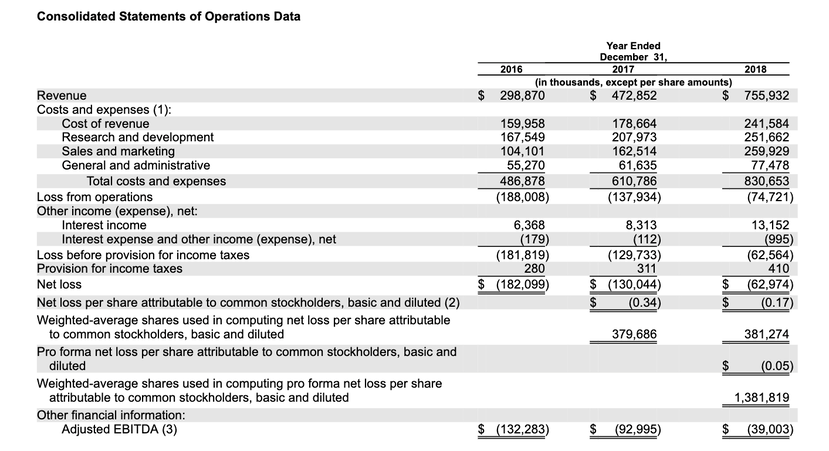

This has allowed the company to show steady revenue growth, which might not be as exciting as the classic Silicon Valley hockey-stick growth, but looks solid. However, the visual social media site is still not profitable. Losses have been decreasing over the last three years and came in at $63m in 2018 - a substantial decrease from the $182m in 2016, but still not enough for some early investors who expected positive profits for 2018. The company warned investors in its filings that it is “still in the early stages of our monetization efforts.

The balance between public ownership and maintaining founder control has become a symbol of tech IPOs. Indeed, the scrapbooking site followed Lyft’s example and issued two classes of shares with different voting powers. In particular, while early backers and the founders have 20 votes per share (Class B), ordinary shareholders have just one vote per share (Class A). Supporters of dual-class structures sustain this allows founders to focus on longer-term goals and protect them from attacks by activist investors.

As clear from the prospectus filed to the SEC, the photo sharing platform views itself as the place “where more than 250 million people around the world go to get inspiration for their lives”- namely a visual search company, rather than a social network. Nonetheless, it cited Snap, Facebook and Twitter as its greatest competitors in its S-1 paperwork. And the reason behind this choice is quite obvious once we consider the main source of revenues for the image sharing platform: advertising.

Together with the most used cost-per-click (CPC) and cost per thousand (CPM) advertising model, Pinterest has created a so-called “pin ad strategy”, which charges advertisers on the engagement or action. That enables the advertiser to pay only when existing users engage with a promoted pin, eventually increasing the potential return on investment.

This has allowed the company to show steady revenue growth, which might not be as exciting as the classic Silicon Valley hockey-stick growth, but looks solid. However, the visual social media site is still not profitable. Losses have been decreasing over the last three years and came in at $63m in 2018 - a substantial decrease from the $182m in 2016, but still not enough for some early investors who expected positive profits for 2018. The company warned investors in its filings that it is “still in the early stages of our monetization efforts.

Despite the fact that it keeps delivering losses, Pinterest rallied in its public market debut, easing concern about “unicorn” listings after the recent stumble by Lyft. Indeed, shares shot up 28% to end their first day of trading at $24.40, with the closing prices valuing the firm at $16bn based on a fully-diluted share count. The news suggested that Wall Street is still hot for the latest tech IPOs.

“Everyone had an interest in the sense that the Lyft debacle left a sour taste in people’s mouths,” said Malcolm Burne, co-founder of StarTech NG, which has pre-IPO investments in Pinterest, Lyft and Uber. “The Pinterest IPO is very important for what happens to Uber because sentiment is everything. If Pinterest goes very well, it will be very good for the whole climate around Uber. You don’t want [Pinterest] coming back down below the IPO price.”

As of today, the shares are trading 16% higher than the IPO price, preparing the market for the incoming listing on the NYSE of the ride-hailing giant Uber.

Data in hands, claiming that Pinterest fits in perfectly in the stereotype of tech unicorn is by no mean a stretch. However, one aspect which differentiates it substantially from other high-growing tech startups is the way it has managed to move steadily and keep its reputation intact rather than “move fast and break things” as Silicon Valley’s mantra suggests. Mr. Silbermann now has to show that a company known for taking small steps rather than chasing growth and innovation can be profitable.

Antonio Maccioni

“Everyone had an interest in the sense that the Lyft debacle left a sour taste in people’s mouths,” said Malcolm Burne, co-founder of StarTech NG, which has pre-IPO investments in Pinterest, Lyft and Uber. “The Pinterest IPO is very important for what happens to Uber because sentiment is everything. If Pinterest goes very well, it will be very good for the whole climate around Uber. You don’t want [Pinterest] coming back down below the IPO price.”

As of today, the shares are trading 16% higher than the IPO price, preparing the market for the incoming listing on the NYSE of the ride-hailing giant Uber.

Data in hands, claiming that Pinterest fits in perfectly in the stereotype of tech unicorn is by no mean a stretch. However, one aspect which differentiates it substantially from other high-growing tech startups is the way it has managed to move steadily and keep its reputation intact rather than “move fast and break things” as Silicon Valley’s mantra suggests. Mr. Silbermann now has to show that a company known for taking small steps rather than chasing growth and innovation can be profitable.

Antonio Maccioni