Source: WRDS and companies’ financial report

Source: WRDS and companies’ financial report

The first sector that one would expect to be strongly hit as a result of a global pandemic that caused multiple lockdowns across the world is the banking sector. Its connection to a stalling real economy could have led to hardships for each company, potentially pushing them into default, and therefore endangering the banks that have supplied them capital.

This has not been the case in the US throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the profits of Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase and Bank of America have been substantially impaired by a combined $48bn of loan loss provisions in the first three quarters of 2020, they were still able to perform remarkably well in the third quarter, achieving a $3.2Bn , $9.4Bn and $2Bn respectively. Goldman Sachs has delivered an annualised ROE of 17.5% for the first nine months of the year, which far exceeded the pre-pandemic expectation of 13%. Morgan Stanley is in line to complete a $7Bn acquisition of Eaton Vance in order to become one of the largest asset managers, reaching $1.2Tn in assets under management. This record performance has its seed in areas such as fixed-income trading and debt and equity underwriting, which have proven extremely lucrative throughout the ups and downs of 2020.

Meanwhile, European and Japanese financial institutions are not keeping up pace with their American peers. Due to their stronger commercial focus, the insurgence of bad loans has had a significant impact since the start of 2020, although most major institutions managed to close the second quarter with a net profit.

US banks are not new in providing an above average performance. After their recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, they have been constantly outperforming their foreign peers from other developed countries. But why?

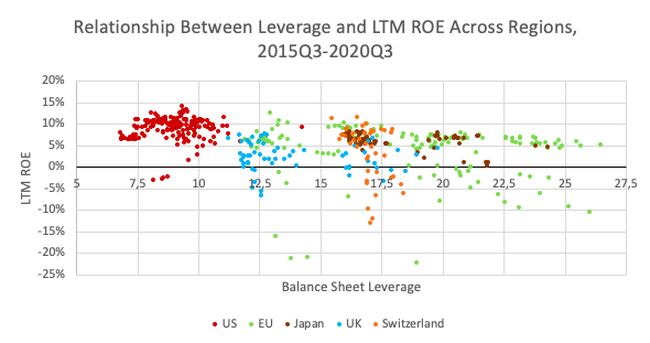

Having a first glance at the financial reports of the largest financial institutions in developed countries, precisely the Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) that have to currently abide to the latest regulatory standard (the TLAC standard), a counterintuitive result is reached. US banks have been able to outperform in terms of Last Twelve Months (LTM) ROE their peers for the last five years, while at the same time maintaining a lower level of balance sheet leverage (computed as the ratio of balance sheet debt to equity). Indeed the average leverage ratio for US Banks was 8.95 (coinciding with the median), against the average of 17.31 and median of 16.86 of foreign banks, while average US bank LTM ROE was 9.01% with a median of 9.61%, and the foreign levels were 4.12% and 5.89% respectively. This is in principle contradicting what is taught in the most basic accounting and corporate finance classes, that is that leverage increases the ROE.

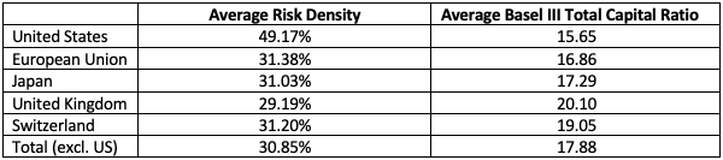

The answer to this puzzle resides in another figure: the risk density of the assets held by each bank. This measure, computed as the ratio of the Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) to the total balance sheet assets, allows an understanding of how risky are a banks activities (both on and off the balance sheet) with respect to what is actually contained in the published financial statements. It then becomes clear that the US banks have a substantially higher risk density than their international peers: the average risk density for the American banks taken into consideration here is 49.17% (with a peak of 63.73% achieved by Wells Fargo), while the one of foreign banks is 30.85%.

This result could have been also reached by looking at the regulatory capital ratios that the banks have to meet due to the Basel III Capital Requirements. All these banks have to meet similar requirements, and they do so according with an average total capital ratio of 17.11. However, there is a difference across geographies, with the US average being 15.65 and the foreign average being 17.88. The reason why US institutions have lower capital ratios while keeping lower leverage is because of the riskiness of their assets, captured by the risk density. It should also be noticed that, from the analysis of the capital ratio, it is possible to eliminate any negative effect of leverage (risk of bankruptcy) as a cause of the inferior performance of foreign banks, as they are more than adequately capitalized with respect to the risk they take on.

Source: WRDS and companies’ financial report, data corresponding to Q1 2020.

Source: WRDS and companies’ financial report, data corresponding to Q1 2020.

The higher risk density is the result of the proportionally higher amount of trading, underwriting and asset management activities taking place in the American institutions, which have proven to be resilient through the pandemic and provided them with higher-than-expected returns. The commercial banking activities have obviously not benefitted from the pandemic, as can be seen by the loan loss provisions applied by the previously mentioned banks and many of the foreign ones included in this study. The institutions that are mostly focused in commercial banking activities have already been in trouble for a while due to the low interest rate environment, which has now been extended even further, and the combination with the pandemic could put these institutions in trouble. The COVID-19 pandemic could thus result as a spark for consolidation in the banking sector, especially in Europe where it has been strongly supported by regulators in the last years, in the hope of catching up with the American institutions.

Tommaso Pirozzi