Since mid-September’s rate crisis, the Fed has been injecting hundreds of billions of dollars into US money markets in order to restore the normal process of borrowing and lending among banks and other firms alleviating funding pressure and ensuring that the financial system has enough liquidity to work smoothly. This article wants to walk us through the logic and the reasons that lead to this type of intervention and describe the actual monetary stance of the american central bank.

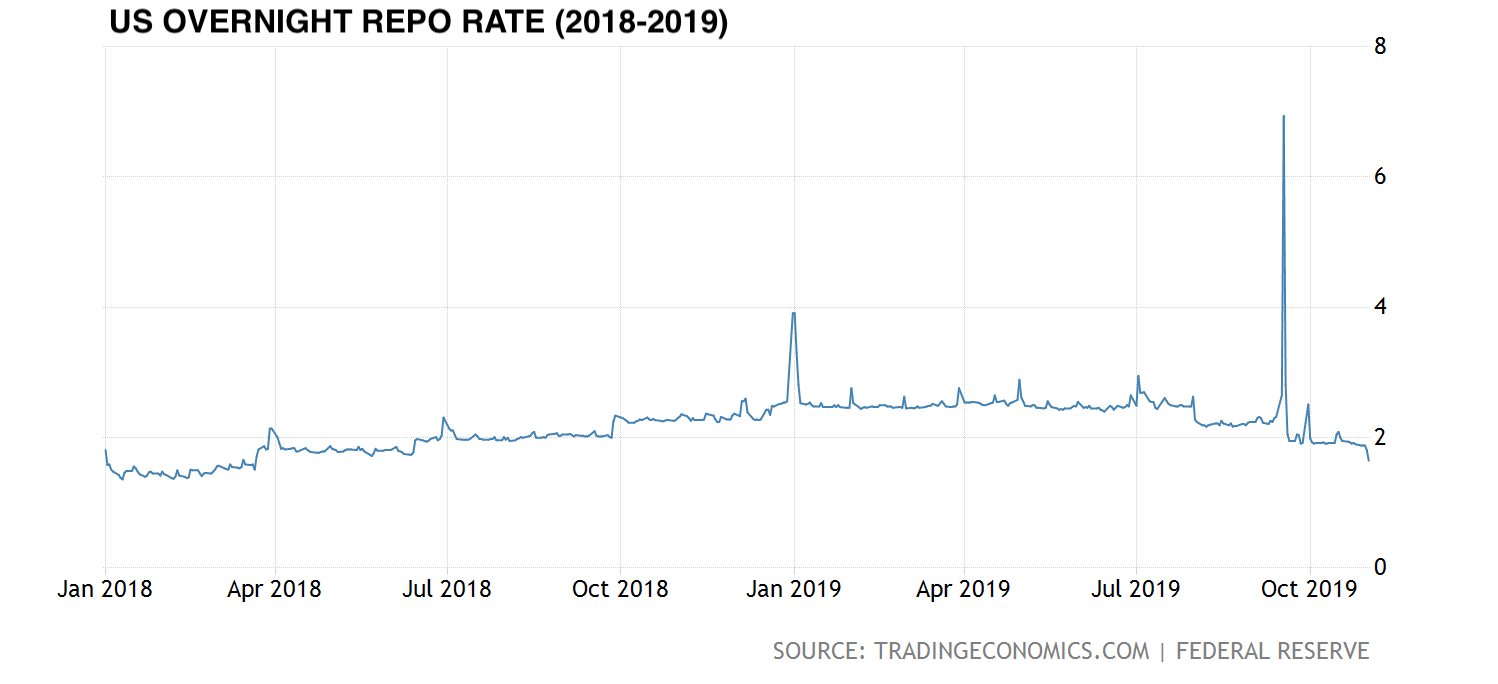

It all started on Monday, September 16th, when the overnight repo agreements rate began to rise until Tuesday, September 17th it spiked to 10% from its target range of 2%-2.25% signaling an abnormal lack of liquidity and prompting accusations that the Fed had lost control of short-term interest rates. The New York Fed – which is responsible for implementing the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy – quickly reacted and stepped in to try to ease the strain with an emergency injection of 75 USD Million to unblock the system and bring the rate back to its desired range. It was the first time since the financial crisis that the Fed had to intervene directly in the repo market. But, let’s take a step back.

It all started on Monday, September 16th, when the overnight repo agreements rate began to rise until Tuesday, September 17th it spiked to 10% from its target range of 2%-2.25% signaling an abnormal lack of liquidity and prompting accusations that the Fed had lost control of short-term interest rates. The New York Fed – which is responsible for implementing the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy – quickly reacted and stepped in to try to ease the strain with an emergency injection of 75 USD Million to unblock the system and bring the rate back to its desired range. It was the first time since the financial crisis that the Fed had to intervene directly in the repo market. But, let’s take a step back.

The United States Overnight Repo Rate decreased to 1.65 on Friday November 1 from 1.81 in the previous trading day. Repo Rate in the United States averaged 2.39 from 1995 until 2019, reaching an all-time high of 6.94 in September of 2019 and a record low of -0.01 in December of 2009.

The repo market is where piles of cash and pools of securities meet, resulting in more than 3 USD Trillion in debt being financed each day. Repo stays for “repurchase agreements”, or collateralized short-term loans transactions, often made overnight. In a repo deal big investors with liquidity surplus – such as mutual funds – can make money by briefly lending cash (that might otherwise sit idle) to those firms with liquidity deficit – such as banks and broker-dealers. In return, these corporations that need to be financed, give held securities for an equivalent until the time when the debt is repaid at a slightly higher price. The difference between the older value of the asset and the new one can be considered the interest rate (the repo rate in this case). A healthy repo market is stable and is more than the world’s biggest pawn shop: it helps a wide range of other transactions go without troubles – including trading in the over 16 USD Trillion U.S. Treasury market. Because of this special link the mid-September turmoil not only affected the repo rate but also the effective federal funds rate (FFR), notably the Fed’s main policy tool and the rate at which banks can borrow from each other, that climbed above the Fed’s target and forced the authorities to act. When the repo rate went up, the FFR also deviated from the central bank’s intended range of 1.75%-2%. Though there isn’t a unique and clear reason as to why this convulsion signed the markets, we could try to give a concrete explanation by looking at a combination of factors that occurred together. First, the Fed could have underestimated the effect caused by many US companies simultaneously withdrew funds to pay their quarterly tax payments. Second, there was a large increase in Treasury bonds being issued by the US government and a consequent steep increase in demand for funds, thus an increase in the rate. Finally, it could also partly be caused by the rising interest rate and the following quantitative tightening of the past few years, leading to diminishing reserves. It is worth noting that there is a big difference between the causes of this repo market agitation and the one that took place in 2008. In that occasion liquidity did not circulate because of the distrust and uncertainty in the banking system: it was a systemic reason. Now the reason is mostly technical: bank’s excess of reserves at the Fed have fallen at high speed since the beginning of 2018 reducing excess of liquidity.

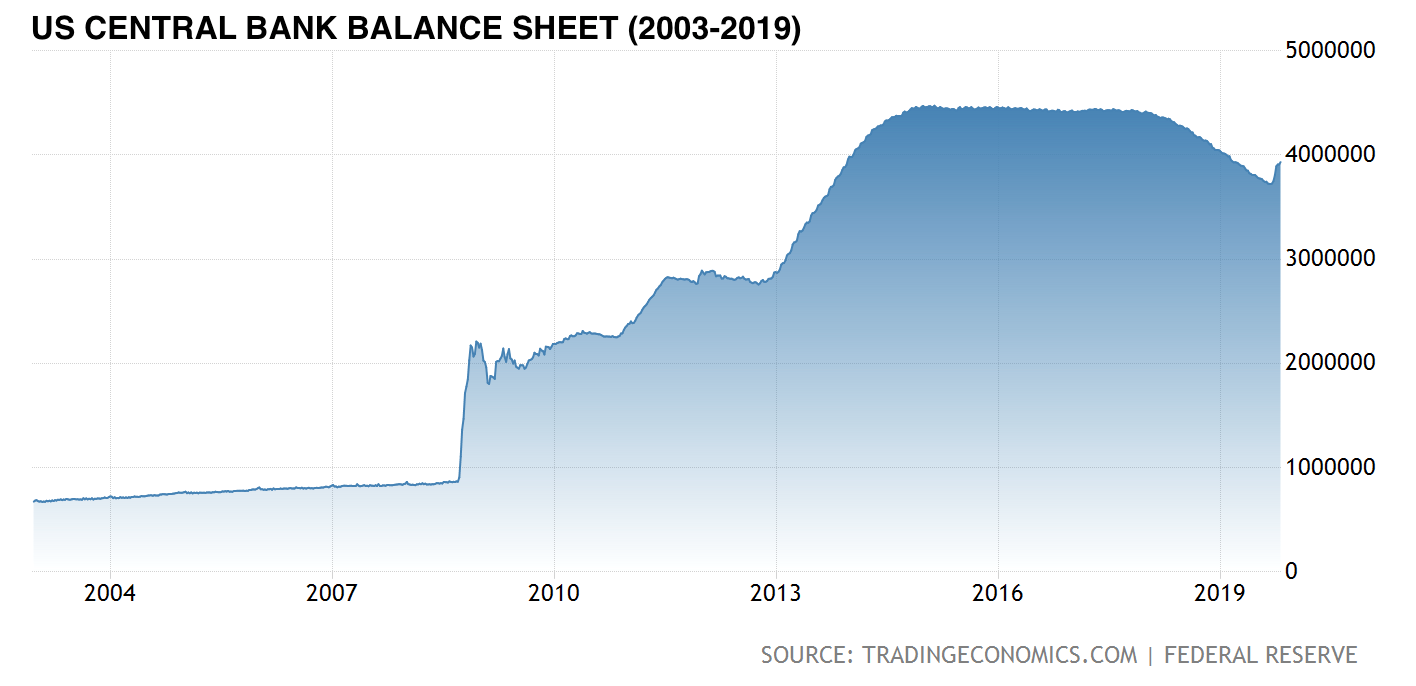

Once last month the Fed started the series of cash injections into the financial system, to control that short-term borrowing rates remained well-behaved, it never stopped. It had been an immediate remedy, but the policymakers and investors were pushing for a longer-term answer to the market’s problems. For this reason, the Fed during October also said it would lend for longer periods, increased its limit on overnight repo operations to at least 120 USD Billion and on Tuesday, October 15th introduced the operation of buying securities (asset purchases). The Fed began buying government-backed securities directly in the market. It announced the plan to buy Treasury bills (which are shorter-debt government debt) at an initial pace of 60 USD Billion per month from mid-October to mid-November and then to adjust both the amounts and timing of bill purchases “as necessary to maintain an ample supply of reserve balances over time” but to continue the purchases until the second quarter of 2020, at least. New purchases amounts are announced on the ninth business day of each month. By expanding its balance sheet, the Fed is increasing the financial system’s supply of bank reserves, which are currency deposits at the US central bank. Its aim is to create a steady supply of dollars to smooth over tumultuous moments and so doing try to keep episodes like last month’s from repeating. This flow of permanent liquidity is impacting the general short-term rates in the economy, but the Fed will also continue to intervene specifically in the repo market with temporary liquidity to ensure large reserves’ supply.

Once last month the Fed started the series of cash injections into the financial system, to control that short-term borrowing rates remained well-behaved, it never stopped. It had been an immediate remedy, but the policymakers and investors were pushing for a longer-term answer to the market’s problems. For this reason, the Fed during October also said it would lend for longer periods, increased its limit on overnight repo operations to at least 120 USD Billion and on Tuesday, October 15th introduced the operation of buying securities (asset purchases). The Fed began buying government-backed securities directly in the market. It announced the plan to buy Treasury bills (which are shorter-debt government debt) at an initial pace of 60 USD Billion per month from mid-October to mid-November and then to adjust both the amounts and timing of bill purchases “as necessary to maintain an ample supply of reserve balances over time” but to continue the purchases until the second quarter of 2020, at least. New purchases amounts are announced on the ninth business day of each month. By expanding its balance sheet, the Fed is increasing the financial system’s supply of bank reserves, which are currency deposits at the US central bank. Its aim is to create a steady supply of dollars to smooth over tumultuous moments and so doing try to keep episodes like last month’s from repeating. This flow of permanent liquidity is impacting the general short-term rates in the economy, but the Fed will also continue to intervene specifically in the repo market with temporary liquidity to ensure large reserves’ supply.

Central Bank Balance Sheet in the United States increased to 3.93 USD Trillion in October 23 from 3.91 USD Trillion in the previous week. Central Bank Balance Sheet in the United States averaged 2.57 USD Trillion from 2002 until 2019, reaching an all-time high of 4.47 USD Trillion in February of 2015 and a record low of 0.67 USD Trillion in January of 2003.

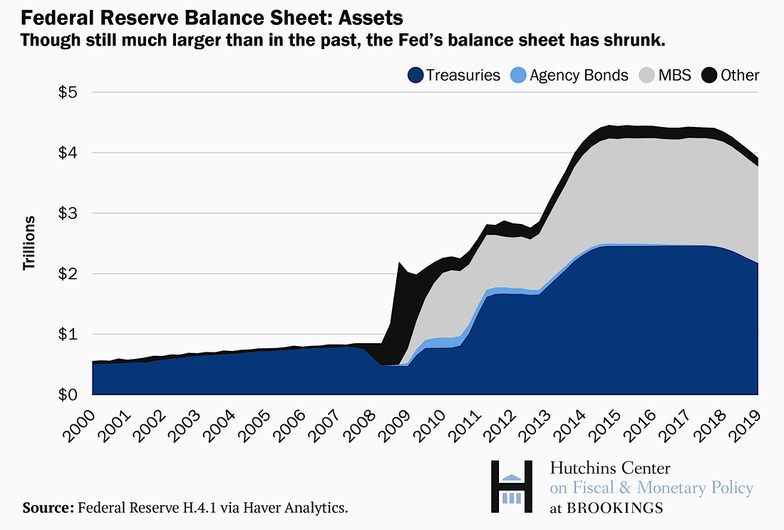

While in years that range from 2000 to 2008 the Fed balance sheet was essentially composed by Treasuries, after the outbreak of the Great Crisis, fueled by an unprecedent financial shock, it had also been enriched by Agency Bonds, Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and Others.

These actions are of considerable size and importance, as seen by the comparison with the post-recession bond-buying campaigns (also called “quantitative easing” or “Q.E.”) where the Fed bought up to US $85 billion per month in securities. However, the FOMC officials are very eager to point out that this program is different from Q.E. As a matter of fact, it is not a change in the Fed’s economic policy stance (so it is not an “unconventional” way of utilizing policy tools) and the action focus remains on short-term securities (Treasury bills as said) rather than longer-term assets. Furthermore, the Fed stresses the point that the new effort is not monetary stimulus but an attempt to keep money markets in check after the episode of mid-September.

The dimension of recent operations has been large, but it has been the practice of the Fed for decades to intervene in markets to add and subtract liquidity to help move short-term borrowing costs to where the central bank wants them, to accomplish its mission to keep inflation stable and to promote job growth (i.e. its well-known symmetric dual mandate with the macro goals of inflation and employment growth).

The dimension of recent operations has been large, but it has been the practice of the Fed for decades to intervene in markets to add and subtract liquidity to help move short-term borrowing costs to where the central bank wants them, to accomplish its mission to keep inflation stable and to promote job growth (i.e. its well-known symmetric dual mandate with the macro goals of inflation and employment growth).

Riccardo Locatelli - 10/11/2019