“The absence of evidence is no evidence of absence.”

… is a known statement describing the phenomenon, in which people like to jump to the conclusion of non-existence, simply because, at the moment, no concrete evidence can be provided for a thing or an event. I cannot see it, I cannot touch it, therefore it must not be real. However, it does not take much to see the logical error at work here – jumping to conclusions is never a good idea. What if evidence disappeared, or will only be available in the future? What if a more intricate method, experiment is required to prove or disprove a fact? So far so good. Taking a step back, the fallacy at work here becomes apparent. After all, especially in investing, it’s best to constantly question one’s approach and to always be in pursuit of a more objective, fact-based view. In fact, this might explain why so many investors give advice along the lines of “be an independent thinker”, “don’t invest based on emotions” or “try to always think contrarian to the masses”

Now that we have established this, let us look at an area of investing where a lot of people are currently trying to jump to conclusions. An area where there is a lot of emotion in the debate. No, this article is not intended to add to the debate around Gamestop, High-Frequency Trading or Altcoins. More so, this article is intended to shine light on a much quieter area of the markets: Value Investing.

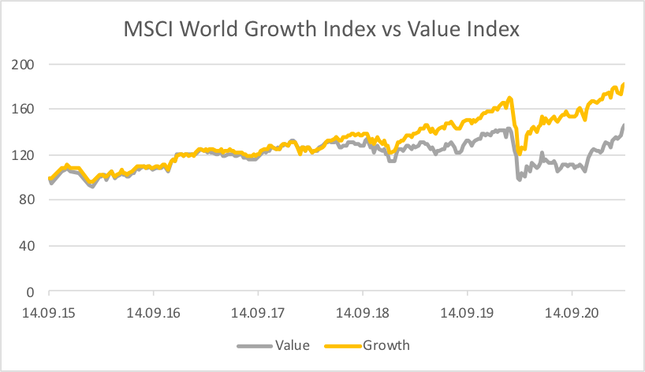

In case you have not heard, the current state of affairs here is a roughly 30-year underperformance (Cliff Asness, 2021) versus Growth Stocks, along with a heated debate on “when value will return” and the volatility of the value premium. To be clear, the situation is dire. Looking only at the past five years, an investment in the Growth Subset of the MSCI-World, would have left you with roughly 20% outperformance compared to the Value-Subset.

… is a known statement describing the phenomenon, in which people like to jump to the conclusion of non-existence, simply because, at the moment, no concrete evidence can be provided for a thing or an event. I cannot see it, I cannot touch it, therefore it must not be real. However, it does not take much to see the logical error at work here – jumping to conclusions is never a good idea. What if evidence disappeared, or will only be available in the future? What if a more intricate method, experiment is required to prove or disprove a fact? So far so good. Taking a step back, the fallacy at work here becomes apparent. After all, especially in investing, it’s best to constantly question one’s approach and to always be in pursuit of a more objective, fact-based view. In fact, this might explain why so many investors give advice along the lines of “be an independent thinker”, “don’t invest based on emotions” or “try to always think contrarian to the masses”

Now that we have established this, let us look at an area of investing where a lot of people are currently trying to jump to conclusions. An area where there is a lot of emotion in the debate. No, this article is not intended to add to the debate around Gamestop, High-Frequency Trading or Altcoins. More so, this article is intended to shine light on a much quieter area of the markets: Value Investing.

In case you have not heard, the current state of affairs here is a roughly 30-year underperformance (Cliff Asness, 2021) versus Growth Stocks, along with a heated debate on “when value will return” and the volatility of the value premium. To be clear, the situation is dire. Looking only at the past five years, an investment in the Growth Subset of the MSCI-World, would have left you with roughly 20% outperformance compared to the Value-Subset.

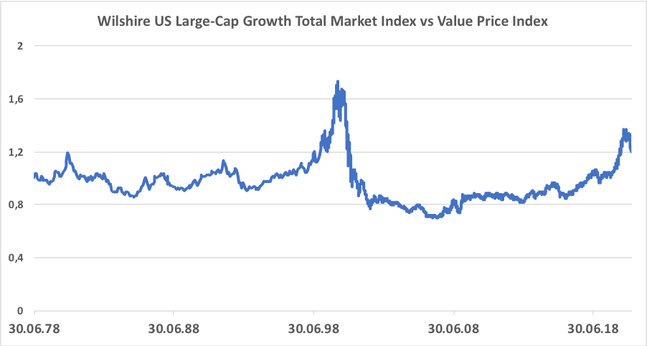

However, looking at the long-term trend here by comparing the market cap of growth and value stock, we can make an interesting observation. Simply put, since the crisis, growth has become more valuable than value. Even up to point where the ratio came close to dot-com-bubble levels.

That some parts of the market might currently be overvalued is an open secret. Nevertheless, the underperformance in value stocks is not attached to an industry. Some attribute that to the fact that “Value is dead”, as Bank of America called it in a research note.

This begs the question now: Where do value returns actually come from? And even more importantly: What happened to the driving force of value returns? Because as we saw in the beginning, just because we cannot observe excess returns in value stocks currently, does not mean it does not exist anymore. And this is where it gets interesting. In 2006 Fama and French published a paper called “The Anatomy of Value and Growth Stock Returns”, the abstract of the paper says the following:

„Average returns on value and growth portfolios are broken into dividends and three sources of capital gain: (1) growth in book equity, primarily from earnings retention, (2) convergence in price-to-book ratios (P/Bs) from mean reversion in profitability and expected returns, and expected returns, and (3) upward drift in P/B during 1927-2006“

Among many other findings, Fama and French point out that, in their sample, returns on value stocks are mainly boosted by increasing price-to-book ratios. In effect, as a value-company, over time, revamps its business, gains market share and therefore is perceived as less risky, investors are willing to pay more for its assets. This ties in neatly with another paper by Fama and French called “Migration” (2007). In this paper, the authors explain that exactly these companies drive the excess returns for value portfolios, compared to growth portfolios. In effect, companies which “migrate” from the cheaper value, to the more expensive (based on P/B valuations) growth territory provide up to 3.5% of excess returns for the aggregate portfolio.

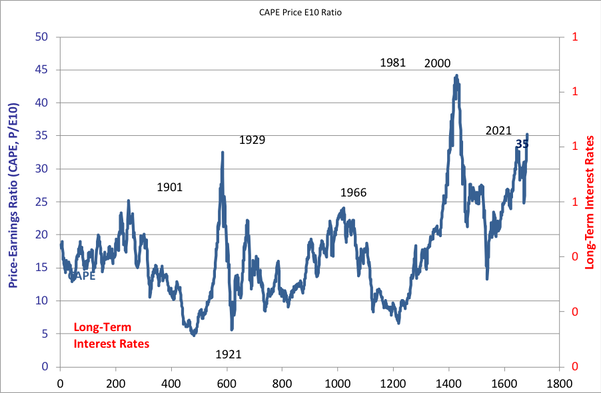

Keeping this in mind, let us go back to the paper we cited initially. What “The long run is lying to you” (Cliff Asness, 2021) now looks at is how these very same changes in valuation have affected the general market over the last decades. Based on the Shiller-Cape value, Asness performs a regression showing that, since the dotcom bubble, valuations dramatically expanded. More importantly, he goes on to show, that much of the phenomenal returns in stocks came from this multiples expansion. In effect, already expensive businesses got even more expensive over time. Looking forward now, expecting these very same stocks to rise even further, would mean expecting them to go even further into bubble territory.

This begs the question now: Where do value returns actually come from? And even more importantly: What happened to the driving force of value returns? Because as we saw in the beginning, just because we cannot observe excess returns in value stocks currently, does not mean it does not exist anymore. And this is where it gets interesting. In 2006 Fama and French published a paper called “The Anatomy of Value and Growth Stock Returns”, the abstract of the paper says the following:

„Average returns on value and growth portfolios are broken into dividends and three sources of capital gain: (1) growth in book equity, primarily from earnings retention, (2) convergence in price-to-book ratios (P/Bs) from mean reversion in profitability and expected returns, and expected returns, and (3) upward drift in P/B during 1927-2006“

Among many other findings, Fama and French point out that, in their sample, returns on value stocks are mainly boosted by increasing price-to-book ratios. In effect, as a value-company, over time, revamps its business, gains market share and therefore is perceived as less risky, investors are willing to pay more for its assets. This ties in neatly with another paper by Fama and French called “Migration” (2007). In this paper, the authors explain that exactly these companies drive the excess returns for value portfolios, compared to growth portfolios. In effect, companies which “migrate” from the cheaper value, to the more expensive (based on P/B valuations) growth territory provide up to 3.5% of excess returns for the aggregate portfolio.

Keeping this in mind, let us go back to the paper we cited initially. What “The long run is lying to you” (Cliff Asness, 2021) now looks at is how these very same changes in valuation have affected the general market over the last decades. Based on the Shiller-Cape value, Asness performs a regression showing that, since the dotcom bubble, valuations dramatically expanded. More importantly, he goes on to show, that much of the phenomenal returns in stocks came from this multiples expansion. In effect, already expensive businesses got even more expensive over time. Looking forward now, expecting these very same stocks to rise even further, would mean expecting them to go even further into bubble territory.

Therefore, it could be concluded that the absence of the value premium was mainly due to the market pushing valuations of already expensive stocks even higher, thereby somewhat muting the effect of recovering value stocks on excess value returns. This also means, that going forward, higher returns from value stocks should be expected, disproving that, just because we cannot see excess value returns at the moment, does not mean, they do not exist.

Tobias Schmidt

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

Tobias Schmidt

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.