Vivendi is French media conglomerate, active in all kinds of media, such as; music, film, gaming and telecommunications. Originally founded as a water company in 1853, Vivendi has strayed far away from its origins. In this path leading to the current configuration of the company, Vivendi’s history has become filled with periods of acquisitions and thereafter periods of divestments to pay down the debt used to finance those acquisitions. This broad approach makes it so that Vivendi and its controlling shareholder Vincent Bolloré have to keep many plates spinning at the same time. This article takes a look at three of the main topics surrounding the French enterprise.

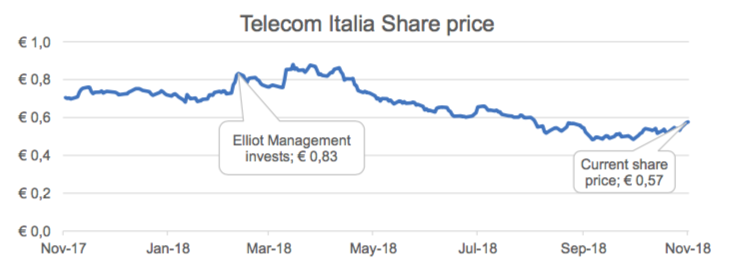

In recent years, the company has sold some of its telecom assets that were a key activity of the group for a considerable amount of time. The only position Vivendi still holds in the industry at the moment is a c.24% stake in Telecom Italia. It is this asset however that has become a major battleground for Vivendi as it struggles for control over the direction of the company with well-known activist investor Elliot Management. The troubles started in March of this year when Elliot began to push for changes to Telecom Italia’s strategy and board members, a key part of Elliot’s plan was to dispose of the fixed-network operations of Telecom Italia. After an almost complete board member resignation forced a full board reshuffle in, Elliot Management ended up being able to appoint 10 out of 15 board seats, with Vivendi controlling the other 5. More recently, Elliot Management has replaced the Vivendi supported CEO with a CEO of its own making it more likely that the strategic repositioning of the business will soon commence. In general, this internal battle has not been good for shareholders as Telecom Italia’s share price has decreased by over 25% since the battle between Vivendi and Elliot Management began. With the board members as well as the CEO replaced, it seems that the restructuring strategy will began to be implemented, with or without Vivendi’s support. Whether it will create any actual shareholder value still remains to be seen.

In recent years, the company has sold some of its telecom assets that were a key activity of the group for a considerable amount of time. The only position Vivendi still holds in the industry at the moment is a c.24% stake in Telecom Italia. It is this asset however that has become a major battleground for Vivendi as it struggles for control over the direction of the company with well-known activist investor Elliot Management. The troubles started in March of this year when Elliot began to push for changes to Telecom Italia’s strategy and board members, a key part of Elliot’s plan was to dispose of the fixed-network operations of Telecom Italia. After an almost complete board member resignation forced a full board reshuffle in, Elliot Management ended up being able to appoint 10 out of 15 board seats, with Vivendi controlling the other 5. More recently, Elliot Management has replaced the Vivendi supported CEO with a CEO of its own making it more likely that the strategic repositioning of the business will soon commence. In general, this internal battle has not been good for shareholders as Telecom Italia’s share price has decreased by over 25% since the battle between Vivendi and Elliot Management began. With the board members as well as the CEO replaced, it seems that the restructuring strategy will began to be implemented, with or without Vivendi’s support. Whether it will create any actual shareholder value still remains to be seen.

A second plate that is worth taking a closer look at is Havas, the advertising and PR company, acquired by Vivendi, after years of speculation, in July 2017. This control was acquired from Vincent Bolloré, which the careful reader might recognize as the man that also owns a controlling stake of Vivendi. While directly owning Havas, Vincent Bolloré had used his control to put his own son, Yannick Bolloré, in place as CEO of the company. In general market perception of the deal was muted. On one hand, it was claimed that the combination of media channels and an advertiser would allow the company to offer unique solutions with great customer insights. On the other hand, the company tried to reassure that Havas would still be able to function as an independent marketing advisor, not having an inherent bias trying to make clients use Vivendi media assets for distribution. Realisations of any possible synergies is most likely no longer the biggest concern when it comes to the acquisition of Havas. Since the acquisition in July 2017, the advertising industry has seen some of its roughest conditions as more and more advertisement spending is being diverted online to the likes of Facebook and Google. Havas is not considered one of the largest players in the space, so they will face an even tougher battle when looking for growth and improved profitability.

The final Vivendi asset worth taking a closer look at is Universal Music Group. Originally split off from the similarly named but currently unrelated Universal Studios in 2004 when Universal Studios merged with NBC, Universal Music Group came under full ownership by Vivendi in 2006. Since then it has been a driver behind the consolidation of the music industry, with among others the acquisition of BMG Music Publishing and the purchase of EMI. In the current status quo of the record label industry, people speak of the big three; Sony Music, Warner Music Group and Universal Music Group. These three labels represent almost 80% of the music market. Universal Music Group has grown into such a powerhouse that it is almost turning Vivendi in to a record label with some extra’s, considering that at least €19bn of Vivendi’s €28.5bn market cap is estimated to come from Universal Music Group. In the current construction, there are some issues. If in an investor were to want to invest in Universal Music Group, one of the largest record labels in the world, it can now only do so by simultaneously buying a stake in a film and television studio, a video game producer and a telecommunication company at the same time. On the other side of the coin, the level of diversification in the assets of Vivendi is being diminished by the large part of its value dependent on UMG. This situation is also something that has come to the attention of Vivendi. Originally the company was considering having an IPO for a minority stake of UMG’s shares but has since scrapped those plans. It deemed a structure where both the subsidiary that makes up most of the value of the parent and the parent itself would be listed at the same time as too complicated. Recently however, the company has started the selection process to find the investment banks that would help Vivendi in finding the right private buyer for a stake in UMG. This will avoid the double listed structure as described previously and provide Vivendi with additional funds. The company has stated that it intends to use this cash for share buybacks as well as new investments.

Any of the three situations described above would be enough to cause grey hairs on the senior management of a normal company, to manage all three at the same tame is a considerably more impressive feat. When considering how intertwined M&A is with the history of Vivendi, if there is anyone that would be up for this job it would be them, just be on the lookout for the sound of breaking tableware.

Joris Jager

The final Vivendi asset worth taking a closer look at is Universal Music Group. Originally split off from the similarly named but currently unrelated Universal Studios in 2004 when Universal Studios merged with NBC, Universal Music Group came under full ownership by Vivendi in 2006. Since then it has been a driver behind the consolidation of the music industry, with among others the acquisition of BMG Music Publishing and the purchase of EMI. In the current status quo of the record label industry, people speak of the big three; Sony Music, Warner Music Group and Universal Music Group. These three labels represent almost 80% of the music market. Universal Music Group has grown into such a powerhouse that it is almost turning Vivendi in to a record label with some extra’s, considering that at least €19bn of Vivendi’s €28.5bn market cap is estimated to come from Universal Music Group. In the current construction, there are some issues. If in an investor were to want to invest in Universal Music Group, one of the largest record labels in the world, it can now only do so by simultaneously buying a stake in a film and television studio, a video game producer and a telecommunication company at the same time. On the other side of the coin, the level of diversification in the assets of Vivendi is being diminished by the large part of its value dependent on UMG. This situation is also something that has come to the attention of Vivendi. Originally the company was considering having an IPO for a minority stake of UMG’s shares but has since scrapped those plans. It deemed a structure where both the subsidiary that makes up most of the value of the parent and the parent itself would be listed at the same time as too complicated. Recently however, the company has started the selection process to find the investment banks that would help Vivendi in finding the right private buyer for a stake in UMG. This will avoid the double listed structure as described previously and provide Vivendi with additional funds. The company has stated that it intends to use this cash for share buybacks as well as new investments.

Any of the three situations described above would be enough to cause grey hairs on the senior management of a normal company, to manage all three at the same tame is a considerably more impressive feat. When considering how intertwined M&A is with the history of Vivendi, if there is anyone that would be up for this job it would be them, just be on the lookout for the sound of breaking tableware.

Joris Jager