Just before WeWork's S-1 registration for an initial public offering to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on August 14th, WeWork was the US's most valuable tech startup. Yet as the investors looked at the prospectus, they seemed to be less excited about the enterprise. They were concerned that the coworking space business model of the group may not be feasible. Most investors were worried about how long-term debt in the form of acquiring or leasing real estate would mix with short-term subscription revenue and whether this model could survive economic downturns. In less than two months, WeWork spiraled from a $47 billion valuation to talk about possible bankruptcy.

The Business Model

The business model of WeWork puts a twist on conventional real estate. It begins by finding a desirable traditional office property, usually in a city where office space is scarce and where there are plenty of young businesses. Instead of purchasing the property, the startup rents the building with a long-term lease. After renting it, they spend substantial amounts improving the building to make it a suitable office space for Gen-X and Gen-Y employees, brought up to believe in the unique office space concept of the tech company. Once the building has been upgraded, WeWork provides office space in small units (one to a few desks) and on short-term contracts (as short as a month). When things go according to plan, as the building gets filled for a given property, the surplus rental income (over the rental payment) is used to cover the cost of maintenance. Once those costs are covered, the economies of scale kick in, creating net income for the company.

Valuation

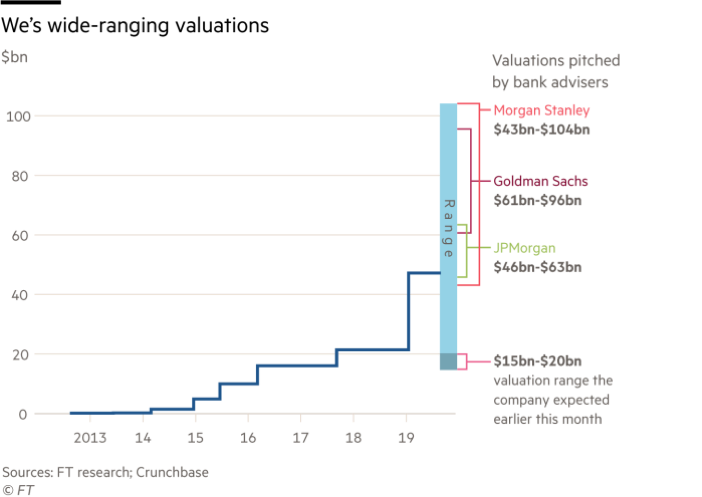

In January, WeWork was worth about $47 billion, after SoftBank's $2 billion funding. That more than doubled its value from its previous two-year round and marked a staggering almost 500x jump from the company's 2012 $97 million valuation.

In 2019, with an abundance of recent acquisitions, the company is aggressively pursuing expansion. So far this year, WeWork has acquired six businesses. In late July, the startup attempted the acquisition of SpaceIQ, a workforce analytics software developer. In June, WeWork acquired Waltz, a real estate investment platform provider, and Prolific Interactive, a brand marketing agency, both for undisclosed amounts. WeWork's parent organization, We, has purchased many of these companies with a mix of cash and its highly valued private shares. "For a lot of these acquisitions, the shareholders and founders that got stock as a big part of the consideration are definitely not happy," said Ben Sun, general partner at Primary Venture Partners. "You get the benefit if [shares] go up, but you also lose if they go down," Mr. Sun added regarding getting paid in stock for an acquisition by private companies.

According to checked pitch books and interviews with people briefed on the project from Financial Times, IPO bankers challenged future valuations much higher than the last transaction Son's SoftBank placed on the company's $47bn price tag. JPMorgan said that the company could be worth between $46bn and $63bn in the listing to WeWork executives. Goldman raised the equity from $61bn to $96bn. In a briefing in 2018, Morgan Stanley projected WeWork's worth at between $43bn and $104bn, though it was set at a more conservative $18bn-$52bn pitch for the IPO.

The Business Model

The business model of WeWork puts a twist on conventional real estate. It begins by finding a desirable traditional office property, usually in a city where office space is scarce and where there are plenty of young businesses. Instead of purchasing the property, the startup rents the building with a long-term lease. After renting it, they spend substantial amounts improving the building to make it a suitable office space for Gen-X and Gen-Y employees, brought up to believe in the unique office space concept of the tech company. Once the building has been upgraded, WeWork provides office space in small units (one to a few desks) and on short-term contracts (as short as a month). When things go according to plan, as the building gets filled for a given property, the surplus rental income (over the rental payment) is used to cover the cost of maintenance. Once those costs are covered, the economies of scale kick in, creating net income for the company.

Valuation

In January, WeWork was worth about $47 billion, after SoftBank's $2 billion funding. That more than doubled its value from its previous two-year round and marked a staggering almost 500x jump from the company's 2012 $97 million valuation.

In 2019, with an abundance of recent acquisitions, the company is aggressively pursuing expansion. So far this year, WeWork has acquired six businesses. In late July, the startup attempted the acquisition of SpaceIQ, a workforce analytics software developer. In June, WeWork acquired Waltz, a real estate investment platform provider, and Prolific Interactive, a brand marketing agency, both for undisclosed amounts. WeWork's parent organization, We, has purchased many of these companies with a mix of cash and its highly valued private shares. "For a lot of these acquisitions, the shareholders and founders that got stock as a big part of the consideration are definitely not happy," said Ben Sun, general partner at Primary Venture Partners. "You get the benefit if [shares] go up, but you also lose if they go down," Mr. Sun added regarding getting paid in stock for an acquisition by private companies.

According to checked pitch books and interviews with people briefed on the project from Financial Times, IPO bankers challenged future valuations much higher than the last transaction Son's SoftBank placed on the company's $47bn price tag. JPMorgan said that the company could be worth between $46bn and $63bn in the listing to WeWork executives. Goldman raised the equity from $61bn to $96bn. In a briefing in 2018, Morgan Stanley projected WeWork's worth at between $43bn and $104bn, though it was set at a more conservative $18bn-$52bn pitch for the IPO.

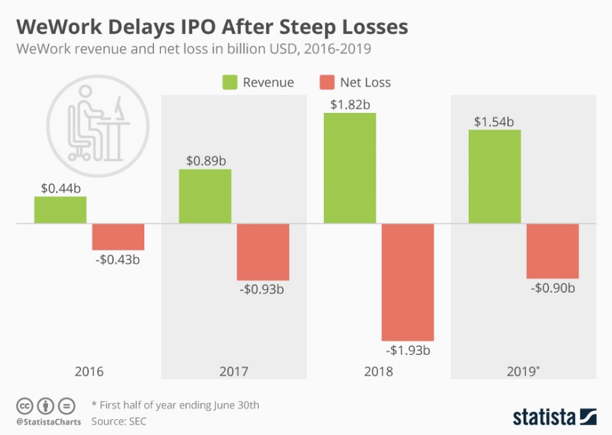

The SEC filings showed that in the first half of 2019, WeWork reported a loss of $900 million on revenue of $1.54 billion. Revenue doubled year-over-year, while expenses rose by 25%. The net losses of the organization were roughly on the same level as its revenue in 2016.

Aswath Damodaran, the notorious New York University professor, wrote in one of his recent articles some of the key features that may make We succeed in the future:

- The office leasing company addresses an unmet and growing need for versatile office space: demand comes from both younger and smaller companies, often uncertain about their future needs, and established businesses, experimenting with new work arrangements. There's a big market, theoretically similar to the company's projected $900 billion.

- With a branded product & economies of scale: WeWork Office is sufficiently differentiated to enable pricing power and higher margins to be possible.

- A continued access to capital, helping the company to fund growth as well as live during mild economic shocks. This exposure, though, is not going to be enough to tide them into deeper recessions, where their debt burden would leave them in trouble.

WeWork needs to stop bleeding cash

We Co. made a request to the Securities and Exchange Commission late in September to withdraw the IPO plan. The company said it would postpone the offer to focus on its core business and that it had "intention[s] to operate WeWork as a public company" but did not provide a time frame. In order to cut costs, the newest co-CEOs of the group, Sebastian Gunningham and Artie Minson, are preparing thousands of job cuts, putting up marginal businesses for sale and purging some luxuries from the former CEO and co-founder, Adam Neumann, such as a G650ER jet bought last year for over $60 million.

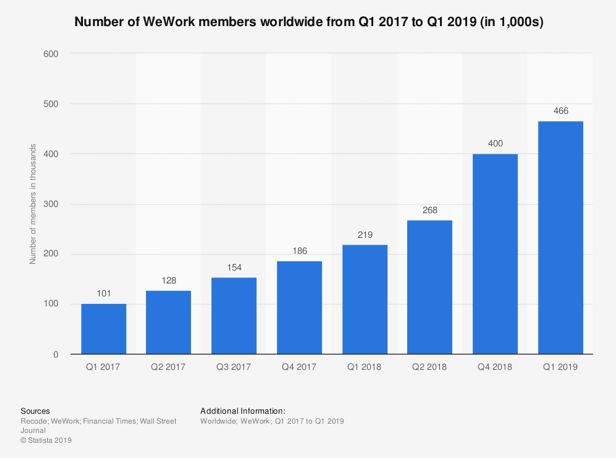

New York-based We had $2.5 billion in cash as of June 30. It would run out of money after the first half of 2020 at the current cash burn rate — about $700 million a quarter. A danger to We in cutting costs is that its growth rates would be dragged down by moves. Most of the previous years, the company doubled its revenue — a quality that it long hoped investors would focus on. Investors say they need to see a clear road to profitability with slower growth.

The company is supposed to need lots of cash to build up its offices regardless of the growth rate. As shown in the previous chart, in 2018, they announced spending of $1.3 billion in net capital expenses — only a fraction of which is represented in the official losses of the company due to the expenditures being accounted for over several years.

We Co. made a request to the Securities and Exchange Commission late in September to withdraw the IPO plan. The company said it would postpone the offer to focus on its core business and that it had "intention[s] to operate WeWork as a public company" but did not provide a time frame. In order to cut costs, the newest co-CEOs of the group, Sebastian Gunningham and Artie Minson, are preparing thousands of job cuts, putting up marginal businesses for sale and purging some luxuries from the former CEO and co-founder, Adam Neumann, such as a G650ER jet bought last year for over $60 million.

New York-based We had $2.5 billion in cash as of June 30. It would run out of money after the first half of 2020 at the current cash burn rate — about $700 million a quarter. A danger to We in cutting costs is that its growth rates would be dragged down by moves. Most of the previous years, the company doubled its revenue — a quality that it long hoped investors would focus on. Investors say they need to see a clear road to profitability with slower growth.

The company is supposed to need lots of cash to build up its offices regardless of the growth rate. As shown in the previous chart, in 2018, they announced spending of $1.3 billion in net capital expenses — only a fraction of which is represented in the official losses of the company due to the expenditures being accounted for over several years.

Filippo Rosaschino - 20/10/2019