In June, General Electric lost its spot in the Dow Jones Industrial Average after 122 years. Only three months later, the first outsider to run GE was nominated, highlighting how the company is desperately trying to accelerate a substantial revamp. In the meanwhile, its market capitalization - which only a decade and a half ago marked it as the world’s most valuable public company – plunged to less than $65bn.

Source: Yahoo Finance

So, what happened to General Electric?

Even if its decline was remarkably exacerbated in the last few years, the roots of this process date back to Jeff Immelt’s direction and, to a certain extent, to the model of growth through acquisition implemented first by Welch.

Jack Welch was the chief executive who led General Electric between 1981 and 2001. Under his guidance, deal making was the main driver behind the exponential increase in the company’s market cap (which peaked at an all-time high of approximately $600bn in 2000). In particular, the successful results of the huge quantity of acquisitions completed in the Welch era contributed to spread the belief that growing through M&A deals was always a winning formula. In his case, however, investor confidence in his abilities made it easier to carry out transactions that increased the share price, encouraging him to do more and more. As a result, when he left in 2001, General Electric was a massive and extended conglomerate, whose businesses ranged from entertainment to insurance, and from plastics to aviation.

Jeff Immelt was appointed as CEO just four days before 9/11. The most striking trend of his performance is the astonishing number of acquisitions and divestitures he carried out. Even if some of those were big winners (for example, Enron’s wind-turbine-manufacturing assets or the sale of the plastics business to Saudi Basic Industries), anyone would agree that terrible capital allocation during his leadership was at the basis of the current GE fall. Indeed, the majority of the transactions realized under Immelt’s guidance proved to be more expensive and less synergistic than promised. Notably, Scott Davis, a longtime GE analyst, has calculated that GE’s total return on Immelt’s acquisitions has been half what the company would have earned by simply investing in stock index mutual funds.

For example, GE acquired as much as nine businesses in the oil and gas industry between 2010 and 2014 – when the price of an oil barrel stood at an all-time high of more than $100. After only two years, with prices down by more than half, GE agreed to combine its oil and gas unit with Baker Hughes. The merged company was mostly owned by GE, and Baker Hughes suffered the subsequent plunge in its stock price (currently at an historical minimum of $21.35).

Another case of awful capital-allocation was GE Capital, the financial services unit. This division, which never accounted for more than 41% of GE profits during Welch’s last decade, was strongly expanded between 2001 and 2007: more than $250bn of debt were added and Immelt allowed investments in riskier assets (such as commercial real estate). In 2007, as much as 55% of GE profits stemmed from it. As soon as the financial crisis exploded the following year, the limits of GE Capital’s investment strategy emerged and even GE’s solvency was questioned: the federal government – with $139bn in loan guarantees - and Warren Buffett had to bail out the company. The division was substantially downsized and plans to dismantle it were announced in 2015.

In 2016, investors started noticing the structural problems that affected the company. First of all, GE was generating far less than it was spending. Between 2015 and 2017, the company originated more or less $30bn from free cash flow and asset sales, while about $75bn were invested in stock buybacks, dividends, and acquisitions. Furthermore, a $31bn underfunded pension fund had to be restocked.

Then, the enormity of GE Power’s issues began to uncover. In 2015, Immelt completed the $10.6bn acquisition of Alstom, a French rival operating in power generation and grid equipment. The rationale for the deal was that it would transform GE’s power equipment division into a dominant global force. However, many aspects made this transaction questionable. On the one hand, while GE’s strategy relied heavily on selling services, regulators made the company divest Alstom’s service business. On the other, its profit margins were low and the acquisition added more than 30,000 high-cost employees. Nevertheless, the most remarkable mistake was the time span when the transaction took place: indeed, GE made a massive investment in natural gas power plants just as renewables were becoming cost competitive.

Consequently, GE Power demand dramatically fell. Part of the decline was also due to the drop in oil and gas prices, which hurt demand from the petrostates - some of GE Power’s biggest customers. The combination of higher inventory and lower earnings reduced the company’s cash flow by $3 billion, while the division’s profits dropped by more than 45%. As the magnitude of the problem became clear, John Flannery was appointed as new chief executive in August 2017. He immediately tried to cut costs through a 12,000-job cut in that division last December. Reducing headcount proved to be a slow process in Europe, especially in France, where Immelt promised the creation of 1,000 additional jobs by the end of 2018.

This replacement, however, was not enough to stop the decline of General Electric and, conversely, the cascade of bleak news even intensified. In January, the company wrote off $6.2bn in connection with a long-term-care insurance business in GE Capital. During the summer, it cut its profits outlook and that it planned to take a non-cash charge for writing down the $23bn of goodwill on the balance sheet of GE Power, most of which was accrued in the Alstom acquisition. Indeed, the French company had a negative net worth of $7bn when it was acquired, and as much as $17bn of goodwill were added to the balance sheet. On top of that, the Securities and Exchange Commission, which was already investigating the Group over its accounting treatment of long-term contracts and provisions for insurance liabilities, widened its probe to include the charges concerning this write-down.

The result was that, in less than one year, the share price crashed by about 50%.

The Flannery era ended on October 1, 2018 when Lawrence Culp replaced him as chief executive of General Electric – becoming the first outsider to head the 126-year-old group. The following day, General Electric’s credit rating has been cut by S&P Global to BBB+ from A (Moody’s confirmed a similar two-notch downgrade at the end of October).

Even if its decline was remarkably exacerbated in the last few years, the roots of this process date back to Jeff Immelt’s direction and, to a certain extent, to the model of growth through acquisition implemented first by Welch.

Jack Welch was the chief executive who led General Electric between 1981 and 2001. Under his guidance, deal making was the main driver behind the exponential increase in the company’s market cap (which peaked at an all-time high of approximately $600bn in 2000). In particular, the successful results of the huge quantity of acquisitions completed in the Welch era contributed to spread the belief that growing through M&A deals was always a winning formula. In his case, however, investor confidence in his abilities made it easier to carry out transactions that increased the share price, encouraging him to do more and more. As a result, when he left in 2001, General Electric was a massive and extended conglomerate, whose businesses ranged from entertainment to insurance, and from plastics to aviation.

Jeff Immelt was appointed as CEO just four days before 9/11. The most striking trend of his performance is the astonishing number of acquisitions and divestitures he carried out. Even if some of those were big winners (for example, Enron’s wind-turbine-manufacturing assets or the sale of the plastics business to Saudi Basic Industries), anyone would agree that terrible capital allocation during his leadership was at the basis of the current GE fall. Indeed, the majority of the transactions realized under Immelt’s guidance proved to be more expensive and less synergistic than promised. Notably, Scott Davis, a longtime GE analyst, has calculated that GE’s total return on Immelt’s acquisitions has been half what the company would have earned by simply investing in stock index mutual funds.

For example, GE acquired as much as nine businesses in the oil and gas industry between 2010 and 2014 – when the price of an oil barrel stood at an all-time high of more than $100. After only two years, with prices down by more than half, GE agreed to combine its oil and gas unit with Baker Hughes. The merged company was mostly owned by GE, and Baker Hughes suffered the subsequent plunge in its stock price (currently at an historical minimum of $21.35).

Another case of awful capital-allocation was GE Capital, the financial services unit. This division, which never accounted for more than 41% of GE profits during Welch’s last decade, was strongly expanded between 2001 and 2007: more than $250bn of debt were added and Immelt allowed investments in riskier assets (such as commercial real estate). In 2007, as much as 55% of GE profits stemmed from it. As soon as the financial crisis exploded the following year, the limits of GE Capital’s investment strategy emerged and even GE’s solvency was questioned: the federal government – with $139bn in loan guarantees - and Warren Buffett had to bail out the company. The division was substantially downsized and plans to dismantle it were announced in 2015.

In 2016, investors started noticing the structural problems that affected the company. First of all, GE was generating far less than it was spending. Between 2015 and 2017, the company originated more or less $30bn from free cash flow and asset sales, while about $75bn were invested in stock buybacks, dividends, and acquisitions. Furthermore, a $31bn underfunded pension fund had to be restocked.

Then, the enormity of GE Power’s issues began to uncover. In 2015, Immelt completed the $10.6bn acquisition of Alstom, a French rival operating in power generation and grid equipment. The rationale for the deal was that it would transform GE’s power equipment division into a dominant global force. However, many aspects made this transaction questionable. On the one hand, while GE’s strategy relied heavily on selling services, regulators made the company divest Alstom’s service business. On the other, its profit margins were low and the acquisition added more than 30,000 high-cost employees. Nevertheless, the most remarkable mistake was the time span when the transaction took place: indeed, GE made a massive investment in natural gas power plants just as renewables were becoming cost competitive.

Consequently, GE Power demand dramatically fell. Part of the decline was also due to the drop in oil and gas prices, which hurt demand from the petrostates - some of GE Power’s biggest customers. The combination of higher inventory and lower earnings reduced the company’s cash flow by $3 billion, while the division’s profits dropped by more than 45%. As the magnitude of the problem became clear, John Flannery was appointed as new chief executive in August 2017. He immediately tried to cut costs through a 12,000-job cut in that division last December. Reducing headcount proved to be a slow process in Europe, especially in France, where Immelt promised the creation of 1,000 additional jobs by the end of 2018.

This replacement, however, was not enough to stop the decline of General Electric and, conversely, the cascade of bleak news even intensified. In January, the company wrote off $6.2bn in connection with a long-term-care insurance business in GE Capital. During the summer, it cut its profits outlook and that it planned to take a non-cash charge for writing down the $23bn of goodwill on the balance sheet of GE Power, most of which was accrued in the Alstom acquisition. Indeed, the French company had a negative net worth of $7bn when it was acquired, and as much as $17bn of goodwill were added to the balance sheet. On top of that, the Securities and Exchange Commission, which was already investigating the Group over its accounting treatment of long-term contracts and provisions for insurance liabilities, widened its probe to include the charges concerning this write-down.

The result was that, in less than one year, the share price crashed by about 50%.

The Flannery era ended on October 1, 2018 when Lawrence Culp replaced him as chief executive of General Electric – becoming the first outsider to head the 126-year-old group. The following day, General Electric’s credit rating has been cut by S&P Global to BBB+ from A (Moody’s confirmed a similar two-notch downgrade at the end of October).

What strategy will be implemented to turn the company’s performance around?

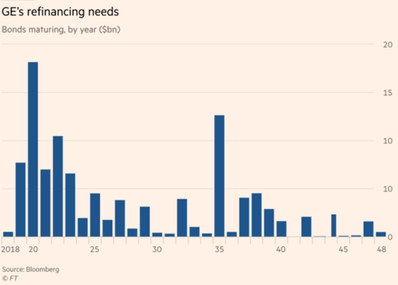

The main challenge Culp needs to face is reducing the company’s huge pile of debt - $115bn at the end of September, with a headline leverage of 5.5x – and he promised to deal with it “with a sense of urgency”.

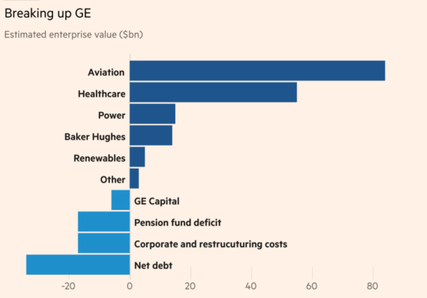

In order to bring the liabilities under control and strengthen the company’s balance sheet, the company is moving forward selling some of its array of assets. For example, a fraction of GE’s stake in Baker Hughes was sold, raising approximately $4bn. The deal, which includes a sale to investors and a buyback by Baker Hughes, will cut GE’s holding in the company from 62.5% to a little over 50%. Besides, a further $1.5bn was ensured by selling its portfolio of loans and leases for healthcare equipment to TIAA Bank. On November 6, the $3.25bn sale of its distributed power business was completed and announced a deal to sell its lighting systems company Current.

These deals are reminders that, in spite of recent difficulties, GE still has a wide range of assets that can attract buyers. The healthcare and life science division is likely to be the next sacrificed. In contrast with the previous plan announced in June, Culp is considering selling just under 50% of the business, spinning off the rest to secure beneficial tax treatment. Analysts have suggested the division’s life sciences business could also be split off and sold separately for about $4bn.

Overall, the target net debt that GE aims to achieve by 2020 is 2.5x EBITDA.

Furthermore, on October 30, GE announced its second dividend cut (to just one cent per share) in less than a year, with a 95% cut from the corresponding 0.24$ payout of 2017. This maneuver will allow GE to retain $4bn. The cash constraints are the result of a net cash flow outflow of $4.1bn in the first three quarters of 2018 combined with a jump in payments into the pension fund to $5.1bn. Despite that, the company argues that it faces no short-term liquidity problems, since only $2bn of the $40bn of bank lending facilities in place are actually withdrawn.

The main challenge Culp needs to face is reducing the company’s huge pile of debt - $115bn at the end of September, with a headline leverage of 5.5x – and he promised to deal with it “with a sense of urgency”.

In order to bring the liabilities under control and strengthen the company’s balance sheet, the company is moving forward selling some of its array of assets. For example, a fraction of GE’s stake in Baker Hughes was sold, raising approximately $4bn. The deal, which includes a sale to investors and a buyback by Baker Hughes, will cut GE’s holding in the company from 62.5% to a little over 50%. Besides, a further $1.5bn was ensured by selling its portfolio of loans and leases for healthcare equipment to TIAA Bank. On November 6, the $3.25bn sale of its distributed power business was completed and announced a deal to sell its lighting systems company Current.

These deals are reminders that, in spite of recent difficulties, GE still has a wide range of assets that can attract buyers. The healthcare and life science division is likely to be the next sacrificed. In contrast with the previous plan announced in June, Culp is considering selling just under 50% of the business, spinning off the rest to secure beneficial tax treatment. Analysts have suggested the division’s life sciences business could also be split off and sold separately for about $4bn.

Overall, the target net debt that GE aims to achieve by 2020 is 2.5x EBITDA.

Furthermore, on October 30, GE announced its second dividend cut (to just one cent per share) in less than a year, with a 95% cut from the corresponding 0.24$ payout of 2017. This maneuver will allow GE to retain $4bn. The cash constraints are the result of a net cash flow outflow of $4.1bn in the first three quarters of 2018 combined with a jump in payments into the pension fund to $5.1bn. Despite that, the company argues that it faces no short-term liquidity problems, since only $2bn of the $40bn of bank lending facilities in place are actually withdrawn.

Source: FT

Over the next year or so, Culp aims to create a smaller but financially healthier version of GE. The focus of the operations will be in just two sectors: aviation and power. However, while the aviation division has world-class technology in a market with excellent long-term growth prospects (accounting for half of the group’s entire value), at the moment GE Power continues to bleed out with year-on-year revenue falling by one-third in the third quarter. The weakness of the power division is particularly worrying for GE because it is intended to be one of the pillars supporting the entire group. The first strategic move of Culp will be to split the power division into two units, one focused on the gas turbines business and the other will manage the remaining assets including steam turbines and grid equipment). In order to tackle GE Power issues, the management structure will be reshaped, ensuring more transparency and more accountability.

In conclusion, while it is impossible to predict the future of General Electric, its steepening decline is a perfect example of the risks associated with growth through acquisitions. Indeed, its fall is not related to the quality of the products the company makes: its jet engines still dominate the global market and its turbines still provide a third of the world’s electricity. On the contrary, GE became so large and complex that it could not manage its own business model.

Pietro Maraldi

In conclusion, while it is impossible to predict the future of General Electric, its steepening decline is a perfect example of the risks associated with growth through acquisitions. Indeed, its fall is not related to the quality of the products the company makes: its jet engines still dominate the global market and its turbines still provide a third of the world’s electricity. On the contrary, GE became so large and complex that it could not manage its own business model.

Pietro Maraldi