Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has captured headlines across the world over the last weeks, as analysts have been trying to discern the broader implications of this geopolitical conflict. One area that is likely to be changed forever by the current conflict is the European energy infrastructure. While Europe’s dependence on Russian oil and gas will deliver a painful blow to the continent’s economies in the short term, the ensuing drive towards energy independence may be a catalyst to the longer-term efforts for more sustainable energy. In this article, we discuss the Ukraine war’s implications for the EU’s green energy transition.

Energy Crisis & Supply Disruptions in Europe

Over the last months, Europe has been dragged into a fight: not only for the territorial integrity of Ukraine but also for global stability and the rules-based international order. For decades, the western approach to trade has been based on the assumption that economic integration would benefit the economy, guarantee peace and lead to an alignment of values. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has upended this worldview and revealed the dangers of economically motivated dependencies, in particular in the energy market.

With its vast natural resources and relatively close geographical proximity, Russia has long established itself as the world’s second-largest oil producer and a leading supplier of a variety of commodities to Europe. It provides about 40% of the EU’s natural gas imports and a quarter of crude oil. It is worth noting that the exposure is not equally distributed, in particular with Italy and Germany much more heavily reliant on Russia than, for example, France. This reflects different attitudes towards alternative energy sources: after the incidents of Chernobyl and Fukushima, both Italy and Germany have become highly skeptical of nuclear energy and imposed moratoria on the construction and use of nuclear reactors, whereas France will continue to build new plants for years to come. In addition, renewable energy accounts for only about 11% of Italy’s energy supply, half the European average.

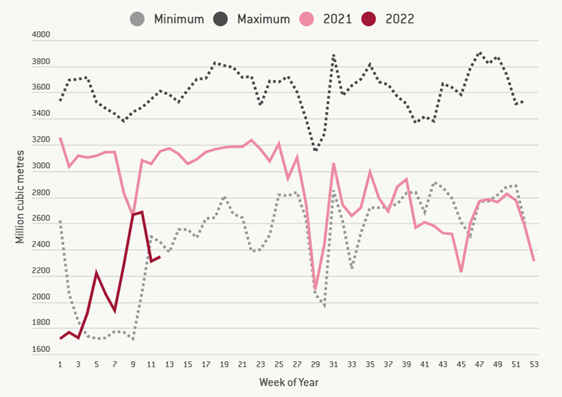

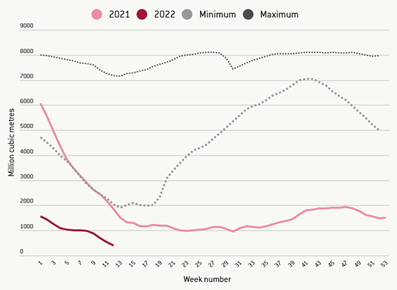

Even before Russia started its war on Ukraine, worries have been mounting about the security of gas supplies as Europe entered the winter with below-average levels of gas storage. While other suppliers have kept their storage levels in line with previous years, Russian state group Gazprom was responsible for the decline: in October, its major gas storage facilities in Germany and Austria were only about 10% and 20% filled, respectively, despite having been full two years previously. Although the European Commission recently proposed legislation to require gas storage facilities to be filled up to 90% this year, this aim will be hard to achieve, especially as the bloc is seeking to reduce imports from its biggest supplier.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has captured headlines across the world over the last weeks, as analysts have been trying to discern the broader implications of this geopolitical conflict. One area that is likely to be changed forever by the current conflict is the European energy infrastructure. While Europe’s dependence on Russian oil and gas will deliver a painful blow to the continent’s economies in the short term, the ensuing drive towards energy independence may be a catalyst to the longer-term efforts for more sustainable energy. In this article, we discuss the Ukraine war’s implications for the EU’s green energy transition.

Energy Crisis & Supply Disruptions in Europe

Over the last months, Europe has been dragged into a fight: not only for the territorial integrity of Ukraine but also for global stability and the rules-based international order. For decades, the western approach to trade has been based on the assumption that economic integration would benefit the economy, guarantee peace and lead to an alignment of values. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has upended this worldview and revealed the dangers of economically motivated dependencies, in particular in the energy market.

With its vast natural resources and relatively close geographical proximity, Russia has long established itself as the world’s second-largest oil producer and a leading supplier of a variety of commodities to Europe. It provides about 40% of the EU’s natural gas imports and a quarter of crude oil. It is worth noting that the exposure is not equally distributed, in particular with Italy and Germany much more heavily reliant on Russia than, for example, France. This reflects different attitudes towards alternative energy sources: after the incidents of Chernobyl and Fukushima, both Italy and Germany have become highly skeptical of nuclear energy and imposed moratoria on the construction and use of nuclear reactors, whereas France will continue to build new plants for years to come. In addition, renewable energy accounts for only about 11% of Italy’s energy supply, half the European average.

Even before Russia started its war on Ukraine, worries have been mounting about the security of gas supplies as Europe entered the winter with below-average levels of gas storage. While other suppliers have kept their storage levels in line with previous years, Russian state group Gazprom was responsible for the decline: in October, its major gas storage facilities in Germany and Austria were only about 10% and 20% filled, respectively, despite having been full two years previously. Although the European Commission recently proposed legislation to require gas storage facilities to be filled up to 90% this year, this aim will be hard to achieve, especially as the bloc is seeking to reduce imports from its biggest supplier.

Chart 1. Russian gas supplies to the EU. Sources: Bruegel, Entsog

Chart 2. Gas storage levels in Gazprom facilities in the EU. Sources: Bruegel, AGSI

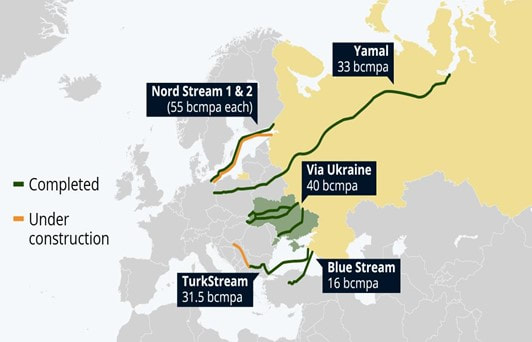

The issue is amplified by potential disruptions of deliveries under current contracts. After the start of the Ukraine invasion, Olaf Scholz, the chancellor of Germany, stopped the approval of Nord Stream 2, an $11 billion pipeline under the Baltic Sea directly linking Russia to north-eastern Germany. Other main supply routes pass through Ukraine, where war activities may damage or destroy older pipelines. In fact, pipelines may even stop operating for less dramatic reasons. For example, on March 23, a pipeline transporting mainly Kazakh oil to Europe was closed after the Russian operator cited a storm damage to its Black Sea port and concerns that European technology export restrictions may delay repairs.

Chart 3. Gas Pipelines connecting Russia and Europe. Sources: JP Morgan via the Economist, Statista

Given these challenges, European leaders as well as the United States government have started intense efforts to diversify the continent’s gas supply and ease some of the price pressures which have fallen on consumers since the beginning of the war. Although the tax break schemes for oil and gas products proposed in various countries will probably help tame inflation, they are not helpful in defining a broader long-term energy strategy. On the other hand, the western allies have intensively lobbied oil and gas producing countries in the Middle East to increase production, though with so far very limited success given their ongoing commitment to OPEC+ arrangements for gradual oil production increases. Also, the proposed shift to more liquified natural gas (LNG) imports, demonstrated by the construction of new LNG terminals in Germany, is not in itself a holistic solution to this complex problem, given the ongoing tightness of the market and the vulnerability to further geopolitical disruptions. As a result, increased interest is drawn to the possibility of a more sustainable, self-reliant future for European energy.

Predicted Path of Energy Transition

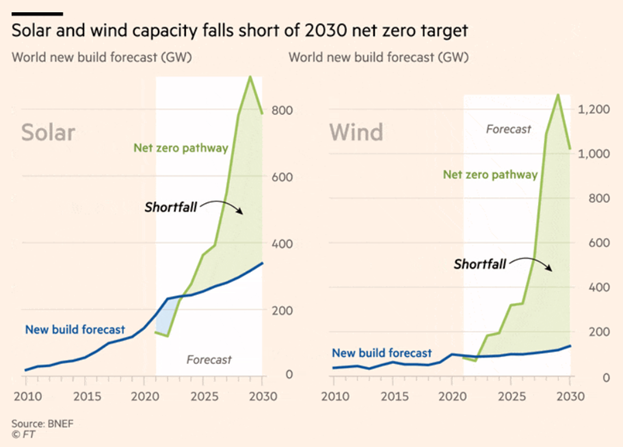

The current energy crisis brought by the aforementioned supply chain disruptions derailed several long-term energy transition plans set forth by global leaders in fossil fuel emissions. In fact, this past November, Glasgow hosted the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) that united global leaders of 197 countries. The aim of this conference was to reinforce the Paris Agreement of maintaining average global temperature of at least 2°C (or an ideal 1.5°C) above pre-industrial levels. Additionally, the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050 was revisited, as the energy sector composes an increasing proportion of greenhouse gas emissions.The net zero goal, however, has become more difficult over the past few years as a result of many countries failing to implement energy and climate policies. At this rate, the net zero goal will fall short by 22 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions worldwide in 2050, something which will be detrimental to climate change.

Predicted Path of Energy Transition

The current energy crisis brought by the aforementioned supply chain disruptions derailed several long-term energy transition plans set forth by global leaders in fossil fuel emissions. In fact, this past November, Glasgow hosted the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) that united global leaders of 197 countries. The aim of this conference was to reinforce the Paris Agreement of maintaining average global temperature of at least 2°C (or an ideal 1.5°C) above pre-industrial levels. Additionally, the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050 was revisited, as the energy sector composes an increasing proportion of greenhouse gas emissions.The net zero goal, however, has become more difficult over the past few years as a result of many countries failing to implement energy and climate policies. At this rate, the net zero goal will fall short by 22 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions worldwide in 2050, something which will be detrimental to climate change.

Chart 4. Solar and Wind Capacity. Source: Financial Times

Setbacks to the Green Energy Transition

The Russia-Ukraine crisis could be a disaster for climate action, further slowing down the global energy transition. In fact, both Russia and Ukraine are key suppliers of crucial metals used in the production of green technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries for electric vehicles. Therefore, the conflict threatens global supplies of these materials, negatively impacting renewable energies capacity. Even before the Russia-Ukraine conflict, global progress towards reducing dependence on fossil fuels was already too slow, while coal was enjoying a comeback as the post-pandemic economic recovery led to high energy demand. Immediately after Alok Sharma asserted “the end of coal is in sight” during the conference in November, coal consumption rose by 18%, and continues to rise as an alternative to Russian fossil fuels. In fact, fears over disruptions to Russian gas supplies are leading to a rush by many European countries to import coal to offset the dependence from Russian gas. The German government is under pressure and is reconsidering its short-term plans to end the use of coal and nuclear power. Italy is also struggling and believes it may need to burn more coal to replace Russian gas. Despite these setbacks, many energy executives believe the transition away from fossil fuels is still happening - though perhaps not as quickly or easily as expected. "These are bumps in the road," says Scott Mackin, managing partner at Denham Capital, a Boston-based sustainable infrastructure fund. "The momentum is still very strong towards the energy transition, in the big picture."

Future Implications

This energy codependency between Russia and the Eurozone resulted in an urgent meeting of the European Commission to discuss an EU-wide energy plan, which set as its central goal full independence of Russian fossil fuels. According to Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, the diversification of gas supply and accelerated transition into renewable energy sources are the only two conceivable ways of becoming independent from Russian energy.

On the 8th March, the President of the European Commission announced the REPowerEU Plan which promised to remove approximately 155 bcm of gas use in excess of the 100 bcm previously projected by 2030. The ⅔ of this cut would be accomplished within a year, thereby eliminating Europe’s overdependence on Russian oil and gas supply. Moreover, it calls for member countries to cease their independence from Russian natural gas altogether by 2027 - a very ambitious goal.

Several European countries had previously drafted plans to transfer into clean energy, such as Germany, that projected to become 100% renewable by 2035, despite the short-term increase in Russian oil and gas consumption. But the net zero plan will require a significant investment of at least $4 trillion globally by 2030, which could heavily weigh on the Eurozone budget.

On the opposite side, Britain and France are looking at the direction of nuclear energy, proposing investments in smaller nuclear reactors - which can be produced in greater numbers - to lower costs. Britain could also build a series of small nuclear fusion reactors, a promising but unproven technology. Ian Chapman, chief executive of the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority, pointed out that every avenue to clean energy must be tried if there is to be any hope of achieving net-zero emissions in three decades (the deadline for avoiding catastrophic climate change).

The path towards green energy transition will require a big long-term commitment from member states. In fact, recent research in the journal Nature found that G20 countries spent $14 million on economic stimulus measures during 2020 and 2021, but only 6% of this was invested in sectors that would cut emissions. However, this crisis may be different, as suggested by Van de Graaf, associate professor of international politics at Ghent University; "Many of the strategies to lower dependence on Russia are the same as the policy measures you want to take to lower emissions". In Europe, he stressed, the war is triggering a wave of investment in clean energy: 'When we have these crises, the [energy] transition can be supercharged'.

Conclusion

Despite all the bad news for the energy transition, the disruptions caused by the conflict in Eastern Europe provide important long-term lessons. Together with the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis has highlighted the need for nations to strengthen their domestic capacity to build clean technologies by investing in renewable energy. Investors, governments, and industry must ensure that any disruption to the world's transition goals is short-lived and must seize this opportunity to make the renewables sector more resilient in the long term. The Russia-Ukraine conflict cannot be allowed to derail attention to an even broader crisis: the worsening climate catastrophe on Earth.

Sources;

By Ana Leticia De Souza Raposo, Martin Stockel, Federico Tita

The Russia-Ukraine crisis could be a disaster for climate action, further slowing down the global energy transition. In fact, both Russia and Ukraine are key suppliers of crucial metals used in the production of green technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries for electric vehicles. Therefore, the conflict threatens global supplies of these materials, negatively impacting renewable energies capacity. Even before the Russia-Ukraine conflict, global progress towards reducing dependence on fossil fuels was already too slow, while coal was enjoying a comeback as the post-pandemic economic recovery led to high energy demand. Immediately after Alok Sharma asserted “the end of coal is in sight” during the conference in November, coal consumption rose by 18%, and continues to rise as an alternative to Russian fossil fuels. In fact, fears over disruptions to Russian gas supplies are leading to a rush by many European countries to import coal to offset the dependence from Russian gas. The German government is under pressure and is reconsidering its short-term plans to end the use of coal and nuclear power. Italy is also struggling and believes it may need to burn more coal to replace Russian gas. Despite these setbacks, many energy executives believe the transition away from fossil fuels is still happening - though perhaps not as quickly or easily as expected. "These are bumps in the road," says Scott Mackin, managing partner at Denham Capital, a Boston-based sustainable infrastructure fund. "The momentum is still very strong towards the energy transition, in the big picture."

Future Implications

This energy codependency between Russia and the Eurozone resulted in an urgent meeting of the European Commission to discuss an EU-wide energy plan, which set as its central goal full independence of Russian fossil fuels. According to Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, the diversification of gas supply and accelerated transition into renewable energy sources are the only two conceivable ways of becoming independent from Russian energy.

On the 8th March, the President of the European Commission announced the REPowerEU Plan which promised to remove approximately 155 bcm of gas use in excess of the 100 bcm previously projected by 2030. The ⅔ of this cut would be accomplished within a year, thereby eliminating Europe’s overdependence on Russian oil and gas supply. Moreover, it calls for member countries to cease their independence from Russian natural gas altogether by 2027 - a very ambitious goal.

Several European countries had previously drafted plans to transfer into clean energy, such as Germany, that projected to become 100% renewable by 2035, despite the short-term increase in Russian oil and gas consumption. But the net zero plan will require a significant investment of at least $4 trillion globally by 2030, which could heavily weigh on the Eurozone budget.

On the opposite side, Britain and France are looking at the direction of nuclear energy, proposing investments in smaller nuclear reactors - which can be produced in greater numbers - to lower costs. Britain could also build a series of small nuclear fusion reactors, a promising but unproven technology. Ian Chapman, chief executive of the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority, pointed out that every avenue to clean energy must be tried if there is to be any hope of achieving net-zero emissions in three decades (the deadline for avoiding catastrophic climate change).

The path towards green energy transition will require a big long-term commitment from member states. In fact, recent research in the journal Nature found that G20 countries spent $14 million on economic stimulus measures during 2020 and 2021, but only 6% of this was invested in sectors that would cut emissions. However, this crisis may be different, as suggested by Van de Graaf, associate professor of international politics at Ghent University; "Many of the strategies to lower dependence on Russia are the same as the policy measures you want to take to lower emissions". In Europe, he stressed, the war is triggering a wave of investment in clean energy: 'When we have these crises, the [energy] transition can be supercharged'.

Conclusion

Despite all the bad news for the energy transition, the disruptions caused by the conflict in Eastern Europe provide important long-term lessons. Together with the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis has highlighted the need for nations to strengthen their domestic capacity to build clean technologies by investing in renewable energy. Investors, governments, and industry must ensure that any disruption to the world's transition goals is short-lived and must seize this opportunity to make the renewables sector more resilient in the long term. The Russia-Ukraine conflict cannot be allowed to derail attention to an even broader crisis: the worsening climate catastrophe on Earth.

Sources;

- EU Commission

- Financial Times

- Focus

- IEA

- Indian Express

- Milano Finanza

- New York Times

- United Nations

- World Economic Forum

- World Nuclear Association

By Ana Leticia De Souza Raposo, Martin Stockel, Federico Tita