Once upon a time there was a land, where almost everyone could start his own business and be successful. It’s the American Dream, it’s United States of America.

But right now, the owners of those companies, the ones founded by successful self-made men are really different.

These owners speak Mandarin and they come from the Far East.

The worst fact… we haven’t nearly realized.

But let’s begin neatly.

How much of the USA is owned by China?

As of January 2018, the Chinese owned $1.17 trillion of U.S. debt, about 19% of Treasury bills, notes, and bonds held by foreign countries. Chinese lenders seized so much of the U.S. debt for one basic economic reason: protecting their “dollar-pegged” yuan as the value of China’s currency has been connected since Bretton Woods to the U.S. dollar. This helps China hold down the cost of its exported goods, which tends to make China a stronger performer in international trade.

But Chinese conglomerates have been buying also stakes in U.S. companies and real estate for years since 1990s. They own part or all of a number of companies that impact American lives on a daily basis. Among the notable acquisitions we find AMC, the nation’s largest movie theater chain bought by Dalian Wanda Group in 2012 for $2.6 billion.

Or GE Appliances. Stoves, refrigerators and dryers from General Electric have been around for more than 100 years, but now the appliance division of the iconic company are Chinese owned. The $5.4 billion deal by Qingdao Haier was China’s largest acquisition of an overseas electronics business.

In the food industry, Smithfield Foods was bought with a $7.1-billion-dollar deal, completed in 2013, that remains the largest purchase of an American firm by a Chinese company.

Additionally, in the hotel industry, Chinese Anabang Insurance Group bought the well-known Waldorf Astoria hotel in Manhattan in 2014 for roughly $2 billion and later Blackstone line of luxury hotels which included assorted Ritz-Carlton locations in California, the Fairmont Scottsdale in Arizona and the Four Seasons Resort in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

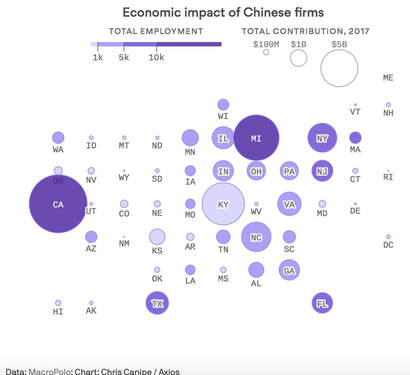

In numbers, Chinese investors own a majority of almost 2,400 American companies employing 114,000 people, about the same number as the combined U.S. staffs of Google, Facebook and Tesla.

But right now, the owners of those companies, the ones founded by successful self-made men are really different.

These owners speak Mandarin and they come from the Far East.

The worst fact… we haven’t nearly realized.

But let’s begin neatly.

How much of the USA is owned by China?

As of January 2018, the Chinese owned $1.17 trillion of U.S. debt, about 19% of Treasury bills, notes, and bonds held by foreign countries. Chinese lenders seized so much of the U.S. debt for one basic economic reason: protecting their “dollar-pegged” yuan as the value of China’s currency has been connected since Bretton Woods to the U.S. dollar. This helps China hold down the cost of its exported goods, which tends to make China a stronger performer in international trade.

But Chinese conglomerates have been buying also stakes in U.S. companies and real estate for years since 1990s. They own part or all of a number of companies that impact American lives on a daily basis. Among the notable acquisitions we find AMC, the nation’s largest movie theater chain bought by Dalian Wanda Group in 2012 for $2.6 billion.

Or GE Appliances. Stoves, refrigerators and dryers from General Electric have been around for more than 100 years, but now the appliance division of the iconic company are Chinese owned. The $5.4 billion deal by Qingdao Haier was China’s largest acquisition of an overseas electronics business.

In the food industry, Smithfield Foods was bought with a $7.1-billion-dollar deal, completed in 2013, that remains the largest purchase of an American firm by a Chinese company.

Additionally, in the hotel industry, Chinese Anabang Insurance Group bought the well-known Waldorf Astoria hotel in Manhattan in 2014 for roughly $2 billion and later Blackstone line of luxury hotels which included assorted Ritz-Carlton locations in California, the Fairmont Scottsdale in Arizona and the Four Seasons Resort in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

In numbers, Chinese investors own a majority of almost 2,400 American companies employing 114,000 people, about the same number as the combined U.S. staffs of Google, Facebook and Tesla.

As a matter of evidence, Chinese trade and investments are among the most divisive topics in the U.S., and a focus of Trump administration. On the other hand, the real preference of Chinese investors is high-tech companies. Chinese investments in U.S. tech startups skyrocketed to $9.9 billion in 2015. US Government therefore realized Beijing’s acquisition of American technologies is enabling a strategic competitor to access the crown jewels of U.S. innovation.

China unveiled right in 2015 a new economic plan, named “Made in China 2025”. The mission shifted from domestic research to investments into foreign markets. At the top of programmed investments there were high-tech industries like artificial intelligence, robotics and space travel. For the increasingly powerful Asian country, it’s the zenith of years of efforts to spend its blossoming wealth in a forward-looking way.

According to president Xi’s words, the plan had much more money on stake and much more coordination between Beijing and Chinese industrialists than previous economic strategies. From 2015 to 2017, Chinese VCs invested into hot companies like Uber and Airbnb, but also dozens of burgeoning firms with no name recognition. China’s leaders want to fill the gaps they have in China’s tech economy.

While the Asian power has earned profits from large manufacturing plants and their low-cost products, the Beijing government perceived they would incur into declining productivity unless its economy adopted high-tech methods.

Essentially, China want to automate entire industries and bring the know-how to do so in-house.

The initiative has skyrocketed investments in American startups that work on robotics, energy equipment and next-generation IT.

Of particular concern to U.S. national security officials is the semiconductor industry, which makes the microchips that provide the heart of many advance technologies that China is trying to leverage. In December 2016, President Barack Obama stopped a Chinese investment fund from acquiring the U.S. subsidiary of a German semiconductor producer.

In September 2017, Trump halted a China investor from buying the American semiconductor maker Lattice, citing national security concerns. And 3 months later a Chinese company’s plan to acquire the American money transfer company MoneyGram fell apart when the CFIUS raised concerns about the fact that personal data of millions of Americans and particularly militaries, could fall into the hands of the Chinese government.

Weeks after that, a Chinese attempt to buy Xcerra, a Massachusetts-based company that makes equipment to test computer chips and circuit boards was stopped. Then Trump blocked the purchase of the chipmaker Qualcomm by Singapore-based Broadcom Ltd.

These are just a few examples. Purchases of US firms by Chinese buyers dropped to US$3 billion in 2018, continuing to decrease from US$55.3 billion in 2016 and US$8.7 billion in 2017, as the escalating trade war dampened deal-making activity. The drop in US purchases took place while M&A activities in the Asia-Pacific saw a 52.4 per cent jump.

The Trump administration put a lot of efforts to block Chinese investments in the US. Congress passed a law that empowered the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), to broaden the scope of reviews of Chinese acquisitions on national security grounds. But on the other hand, very cunningly, Chinese investors have shifted their interest to early-seed financing of tech firms in Silicon Valley and low-profile purchases in order to deceive CFIUS.

The phenomenon is far beyond a mere M&A open-market issue.

It involves bigger and more complex geopolitical equilibria.

But whether China will have to face a tough path to get the tech know-how, what will happen next?

What if we should face the idea of a new first economic power?

Elena Donati

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

China unveiled right in 2015 a new economic plan, named “Made in China 2025”. The mission shifted from domestic research to investments into foreign markets. At the top of programmed investments there were high-tech industries like artificial intelligence, robotics and space travel. For the increasingly powerful Asian country, it’s the zenith of years of efforts to spend its blossoming wealth in a forward-looking way.

According to president Xi’s words, the plan had much more money on stake and much more coordination between Beijing and Chinese industrialists than previous economic strategies. From 2015 to 2017, Chinese VCs invested into hot companies like Uber and Airbnb, but also dozens of burgeoning firms with no name recognition. China’s leaders want to fill the gaps they have in China’s tech economy.

While the Asian power has earned profits from large manufacturing plants and their low-cost products, the Beijing government perceived they would incur into declining productivity unless its economy adopted high-tech methods.

Essentially, China want to automate entire industries and bring the know-how to do so in-house.

The initiative has skyrocketed investments in American startups that work on robotics, energy equipment and next-generation IT.

Of particular concern to U.S. national security officials is the semiconductor industry, which makes the microchips that provide the heart of many advance technologies that China is trying to leverage. In December 2016, President Barack Obama stopped a Chinese investment fund from acquiring the U.S. subsidiary of a German semiconductor producer.

In September 2017, Trump halted a China investor from buying the American semiconductor maker Lattice, citing national security concerns. And 3 months later a Chinese company’s plan to acquire the American money transfer company MoneyGram fell apart when the CFIUS raised concerns about the fact that personal data of millions of Americans and particularly militaries, could fall into the hands of the Chinese government.

Weeks after that, a Chinese attempt to buy Xcerra, a Massachusetts-based company that makes equipment to test computer chips and circuit boards was stopped. Then Trump blocked the purchase of the chipmaker Qualcomm by Singapore-based Broadcom Ltd.

These are just a few examples. Purchases of US firms by Chinese buyers dropped to US$3 billion in 2018, continuing to decrease from US$55.3 billion in 2016 and US$8.7 billion in 2017, as the escalating trade war dampened deal-making activity. The drop in US purchases took place while M&A activities in the Asia-Pacific saw a 52.4 per cent jump.

The Trump administration put a lot of efforts to block Chinese investments in the US. Congress passed a law that empowered the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), to broaden the scope of reviews of Chinese acquisitions on national security grounds. But on the other hand, very cunningly, Chinese investors have shifted their interest to early-seed financing of tech firms in Silicon Valley and low-profile purchases in order to deceive CFIUS.

The phenomenon is far beyond a mere M&A open-market issue.

It involves bigger and more complex geopolitical equilibria.

But whether China will have to face a tough path to get the tech know-how, what will happen next?

What if we should face the idea of a new first economic power?

Elena Donati

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.