The outlook

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank has attracted the attention of the markets as one of the key and more influential players and made the news for many reasons. From the heavy divestiture strategy, moving to the “Nasdaq whale” bets and ending with the talks of a potential delisting of the company, Masayoshi Son’s group has been on the headlines of the newspapers as never before and now attempts to shore up confidence in its performance after warning of a $13bn annual operating loss after its $100bn investment fund was severely affected by the market turmoil widespread by the coronavirus outbreak.

The asset divestiture

Indeed, the pandemic forced the Japanese group to rethink his business structure and implement important change of routes. The important losses the group has suffered during the months of the pandemic concerned that the group may not pay a dividend for the first time since the 1994 listing. At the height of the coronavirus crisis in March, the group launched an asset sale programme to fund $41bn in share buybacks and debt repayments. As a result, while net debt rose to $64bn from $55bn at the end of December, there was a decline in shareholders’ value from $212bn to $202bn. With the recent disposals, SoftBank has well surpassed its target and the newly acquired cash will open a spectrum of options for Mr Son as he examines taking more aggressive bets on publicly listed technology companies.

The last Telecom asset has been sold at the end of September, when SoftBank agreed to sell US mobile phone distributor Brightstar, ending its status as a global telecom operator. Brightstar Global Group’s shares were sold to a newly formed subsidiary of Brightstar Capital Partners, the private equity fund, and although the size of the transaction was not disclosed, people close to the company revealed that SoftBank made a loss on this investment. The group acquired Brightstar in 2014 for $1.7bn and now plans to keep a 40 per cent stake in its listed domestic telecoms subsidiary, but will avoid to hold a majority stake in any telecoms business.

Moreover, SoftBank’s founder decided to downsize what has been the most lucrative investment of his career, the stake in Alibaba. After 15 years he resigned from Alibaba’s board and obtained $11.5bn by selling some of its shares.

The sale that really allowed SoftBank to reach its goal has been the trade of a big portion of its stake in T-Mobile US, raising $14.8bn in a share sale that priced the telecom company’s stock at $103 each, a discount of less than 4 per cent to its closing price at $107. A further agreement was also signed between SoftBank and Deutsche Telekom, which will own Softbank’s remaining T-Mobile shares worth $10bn. The deal was structured as a call option which gives a four years-right to Deutsche Telekom to become the major shareholder of the company. SoftBank obtained an almost 25 per cent of the company when T-Mobile and Spirit, which was controlled by the Japanese conglomerate with an 80 per cent stake, finally combined after months of contacts and negotiations.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank has attracted the attention of the markets as one of the key and more influential players and made the news for many reasons. From the heavy divestiture strategy, moving to the “Nasdaq whale” bets and ending with the talks of a potential delisting of the company, Masayoshi Son’s group has been on the headlines of the newspapers as never before and now attempts to shore up confidence in its performance after warning of a $13bn annual operating loss after its $100bn investment fund was severely affected by the market turmoil widespread by the coronavirus outbreak.

The asset divestiture

Indeed, the pandemic forced the Japanese group to rethink his business structure and implement important change of routes. The important losses the group has suffered during the months of the pandemic concerned that the group may not pay a dividend for the first time since the 1994 listing. At the height of the coronavirus crisis in March, the group launched an asset sale programme to fund $41bn in share buybacks and debt repayments. As a result, while net debt rose to $64bn from $55bn at the end of December, there was a decline in shareholders’ value from $212bn to $202bn. With the recent disposals, SoftBank has well surpassed its target and the newly acquired cash will open a spectrum of options for Mr Son as he examines taking more aggressive bets on publicly listed technology companies.

The last Telecom asset has been sold at the end of September, when SoftBank agreed to sell US mobile phone distributor Brightstar, ending its status as a global telecom operator. Brightstar Global Group’s shares were sold to a newly formed subsidiary of Brightstar Capital Partners, the private equity fund, and although the size of the transaction was not disclosed, people close to the company revealed that SoftBank made a loss on this investment. The group acquired Brightstar in 2014 for $1.7bn and now plans to keep a 40 per cent stake in its listed domestic telecoms subsidiary, but will avoid to hold a majority stake in any telecoms business.

Moreover, SoftBank’s founder decided to downsize what has been the most lucrative investment of his career, the stake in Alibaba. After 15 years he resigned from Alibaba’s board and obtained $11.5bn by selling some of its shares.

The sale that really allowed SoftBank to reach its goal has been the trade of a big portion of its stake in T-Mobile US, raising $14.8bn in a share sale that priced the telecom company’s stock at $103 each, a discount of less than 4 per cent to its closing price at $107. A further agreement was also signed between SoftBank and Deutsche Telekom, which will own Softbank’s remaining T-Mobile shares worth $10bn. The deal was structured as a call option which gives a four years-right to Deutsche Telekom to become the major shareholder of the company. SoftBank obtained an almost 25 per cent of the company when T-Mobile and Spirit, which was controlled by the Japanese conglomerate with an 80 per cent stake, finally combined after months of contacts and negotiations.

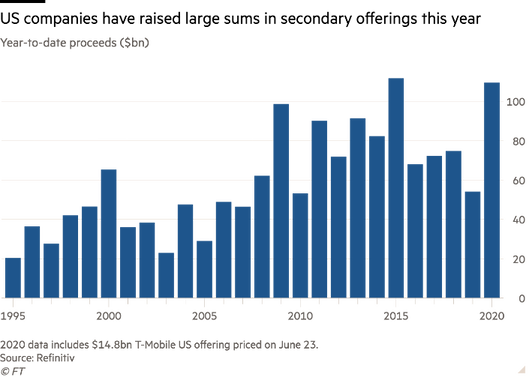

Secondary offering is the sale of new or closely held shares by a company that has already made an initial public offering (IPO).

It can be non-dilutive when existing shares are sold by existing shareholders, or dilutive when company itself creates and places new shares onto the market.

The chart shows how much the US companies have raised through secondary offerings: 2020 is the second ever greatest value, second only to 2015

It can be non-dilutive when existing shares are sold by existing shareholders, or dilutive when company itself creates and places new shares onto the market.

The chart shows how much the US companies have raised through secondary offerings: 2020 is the second ever greatest value, second only to 2015

The series of transactions are expected to inject more than $20bn into the Japanese group and include an offering of common stock, mandatory convertible shares and rights offering, together with the additional shares that the underwriters investment banks can sell if there is sufficient investor demand, known as the “greenshoe” option. T-Mobile made the biggest secondary stock offering of the year in order to sell SoftBank’s stake and a group of banks including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley underwrote the offering. This $20bn secondary offering has been almost the greatest since the financial crisis, second only to the $20.7bn sale of AIG stock made by the US Treasury in 2012.

A third important divestiture made this year by SoftBank has been the sale of the UK’s Arm Holding to US chip company Nvidia. The cash-and-stock takeover comes just four years after Mr Son bought the chip designer and values the UK company more than $40bn. Nvidia will pay the Japanese group $21.5bn in common shares, $12bn in cash, an additional $5bn in cash if Arm reaches some financial performances targets and Nvidia will also issue $1.5bn in equity to Arm employees. When Masayoshi Son bought the chip designer in 2016 paid $32bn for the business and said it would be the centre for the future of the technology group. Arm clearly underperformed under the Japanese group’s ownership; Nvidia had a market valuation similar to that of Arm’s in 2016, but now trades with a market value that is 10 times the amount SoftBank paid in cash for Arm. This deal, which is the largest ever in the semiconductor industry, made SoftBank the largest shareholder of the US chipmaker with a stake around 7 per cent.

A third important divestiture made this year by SoftBank has been the sale of the UK’s Arm Holding to US chip company Nvidia. The cash-and-stock takeover comes just four years after Mr Son bought the chip designer and values the UK company more than $40bn. Nvidia will pay the Japanese group $21.5bn in common shares, $12bn in cash, an additional $5bn in cash if Arm reaches some financial performances targets and Nvidia will also issue $1.5bn in equity to Arm employees. When Masayoshi Son bought the chip designer in 2016 paid $32bn for the business and said it would be the centre for the future of the technology group. Arm clearly underperformed under the Japanese group’s ownership; Nvidia had a market valuation similar to that of Arm’s in 2016, but now trades with a market value that is 10 times the amount SoftBank paid in cash for Arm. This deal, which is the largest ever in the semiconductor industry, made SoftBank the largest shareholder of the US chipmaker with a stake around 7 per cent.

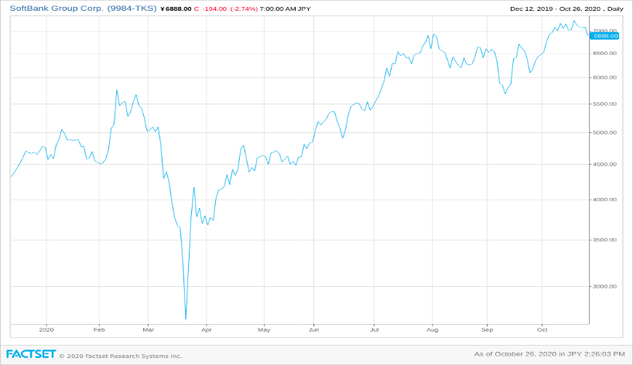

The chart shows the stock price of SoftBank group. In March, the share suffered a single day fall in price of 17 per cent. In May, SoftBank’s shares have risen 72 per cent since buybacks were announced in March. In August, it planned $14bn sale of shares in its telecom units. In September, announced the sale of Arm to Nvidia for up to $40bn.

Conclusion

The Japanese colossus has bounced back from historic loss and posted $12bn quarterly profit, but will maintain for the rest of the year a low-risk investment strategy and will secure cash to improve its financial health. Investors have always been uncertain about what Softbank really is and where will be in a month, a year or a decade: the lunch of the huge Vision Fund made people think it has transformed into a PE fund, the recent “Nasdaq whale” bets classified it as a hedge fund but in general it can be best characterised as a global investment and asset management powerhouse. What is certain is that despite the huge sell-off in its core telecom and tech businesses, SoftBank group and its forward-looking leader strongly believe in the continuation of his technology bets in the era of Artificial Intelligence.

Edoardo Zanetta

The Japanese colossus has bounced back from historic loss and posted $12bn quarterly profit, but will maintain for the rest of the year a low-risk investment strategy and will secure cash to improve its financial health. Investors have always been uncertain about what Softbank really is and where will be in a month, a year or a decade: the lunch of the huge Vision Fund made people think it has transformed into a PE fund, the recent “Nasdaq whale” bets classified it as a hedge fund but in general it can be best characterised as a global investment and asset management powerhouse. What is certain is that despite the huge sell-off in its core telecom and tech businesses, SoftBank group and its forward-looking leader strongly believe in the continuation of his technology bets in the era of Artificial Intelligence.

Edoardo Zanetta