Car industry is one of the most important sectors of the German economy, which in turn accounts for one third of the entire eurozone aggregate output. Quarterly reports of firms in the sector for the third quarter of 2018 have shown a decline in profitability, which comes as a result of the delays in meeting new emission standards and the trade war between the US and China. The failure to prove timely compliance with the new emission regulation called Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), which entered into force on September 1st, slowed down production and led to a great amount of unsold finished goods: as an example, Volkswagen had 250,000 unsold vehicles all around Europe at the end of the summer.

WLTP in fact requires all cars to be tested under new conditions before being ready for sale, and Germany’s low levels of unemployment in recent years has caused a skills shortage which is in part responsible for not meeting the deadline. Another factor that contributed to the delays is the so-called “Dieselgate” scandal over illegal emissions, together with the possibility of a prohibition of diesel cars in some German (or even European) cities, which worried carmakers about further consequences and sanctions, and therefore had them focused on updating their cars software thoroughly to meet new standards.

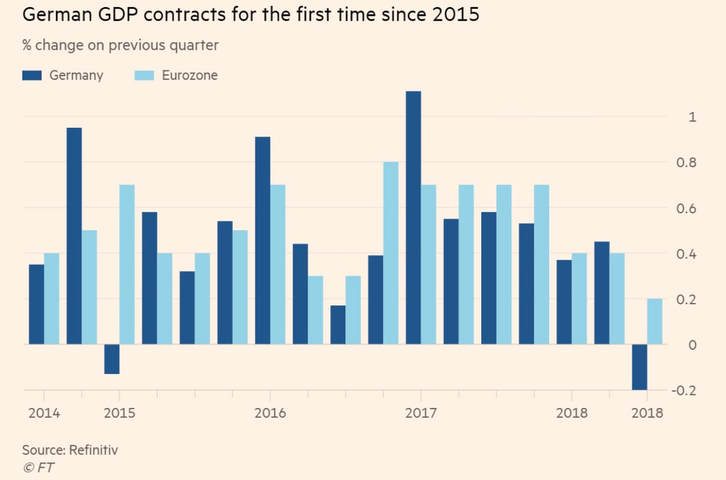

However, what’s most important is the effect of the decline in profitability and delays of the car industry on German GDP: gross domestic product has declined by 0.2% in the third quarter, which represents the first contraction since 2015. But the phenomenon is not limited to Germany alone: in general, eurozone GDP, which deeply depends on the German economy as previously mentioned, registered the worst growth rate of the last four years (only +0.2%).

WLTP in fact requires all cars to be tested under new conditions before being ready for sale, and Germany’s low levels of unemployment in recent years has caused a skills shortage which is in part responsible for not meeting the deadline. Another factor that contributed to the delays is the so-called “Dieselgate” scandal over illegal emissions, together with the possibility of a prohibition of diesel cars in some German (or even European) cities, which worried carmakers about further consequences and sanctions, and therefore had them focused on updating their cars software thoroughly to meet new standards.

However, what’s most important is the effect of the decline in profitability and delays of the car industry on German GDP: gross domestic product has declined by 0.2% in the third quarter, which represents the first contraction since 2015. But the phenomenon is not limited to Germany alone: in general, eurozone GDP, which deeply depends on the German economy as previously mentioned, registered the worst growth rate of the last four years (only +0.2%).

As a consequence of these figures, we might expect a revision of future monetary policies by the European Central Bank: although Mario Draghi confirmed on November 26 that the bank will end quantitative easing by the end of December, the problems in the car making industry and the growth slowdown will probably cause a change in the timeline for the first interest rate increase since the Euro crisis. While the industry might be able to recover in a few months, the global macroeconomic outlook for 2019 has definitely changed. When the ECB will declare its interest rate strategy for the following year, we can expect the central bank stimulus to continue throughout the whole 2019, with interest rates remaining at low historical levels at least up until September 2019, analysts say.

Accommodative monetary policy doesn't necessarily represent a bad news for European markets however: given the fact that inflation is expected to remain under control and probably well below the 2% threshold set by European treaties, and that regional growth will be back on track, not increasing interest rates in 2019 could potentially help the pricing of European bonds by governments in need of funding such as Italy, and could lead to further investments and stock market growth, therefore opposing the negative signal from the real economy. Note that the revised forecast for future economic European growth decreased to 1.6% this year, as opposed to the 2.2% recorded in 2017.

This further good news for the markets, supported by an expected recovery of the car industry once emission standards will be met in the following months, ultimately rests on the strategic decision of the ECB and on the weight that the latter will give to the decline in profitability previously discussed.

Gianluca Sobrero