The deal struck in 2017 between Foxconn, the Taiwanese technology giant and Scott Walker, back then governor of Wisconsin, stated that Foxconn would receive $4.5 billion in State incentives in exchange for a pledge to invest approximately $10 billion and employ 13,000 people, a significant portion of whom would be constituted by ‘blue-collar workers’.

The agreement hailed by Mr. Trump as his personal victory, however, has generated some turbulence, due to the outbreak of the global trade war, to the shifts in the US political climate and, finally, to a slowdown in the smartphone industry sales, from which Foxconn has been strongly impacted. After almost two years, Foxconn is yet to deliver the aforementioned capital and the workforce.

This leads to some doubts on the feasibility of Foxconn project, which seems to show some similarities with the Amazon case: indeed, the tech giant decided to change its plans to establish a headquarters in New York.

The skepticism about cost and benefit ratio of the Foxconn project emerged long before the trade war inception. A detailed study by the Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau concluded that the deal would not pass its breakeven point until at least the 2042-43 fiscal year, and even this forecast appeared as highly optimistic. The report overconfidently projected a significant magnitude of income tax inflows and failed in not recognize the additional expenditures associated with public services that would be inevitable for such a large-scale project.

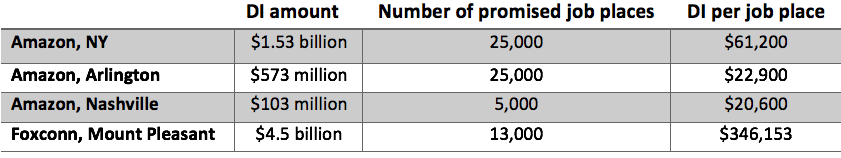

In addition, the deal appeared extraordinary in terms of the average incentive per job place provided by the US government, which is notoriously severe in providing subsidies. According to Timothy Bartik, from the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Foxconn planned to receive an amount of subsidy per promised workplace several times larger than the one historically provided by the US government.

The exceptionality of the dimension of Foxconn subsidy is best demonstrated by the comparison against possible subsidization of Amazon. Amazon press release reported that Amazon would have received around $1.2 billion in refundable tax credit and a cash grant of $325 million over the following decade, in exchange for 25,000 workplaces to be generated in Long Island City, New York. In Arlington, Virginia, where the tech giant would have added another 25,000 jobs, it would have been provided a cash grant of $570 million. Similarly, another $100 million in cash grant for capital expenditures and job tax credit would have been offered over the following seven years in Nashville, Tennessee, for hiring 5,000 employees.

In general, the uncertainty of such projects makes the prediction of its costs a highly demanding task. Jeffrey Dorfman, from the University of Georgia, estimated that the Foxconn deal would have had cost of at least $230,000 per job for a local taxpayer, whereas Tim Culpan from Bloomberg claimed that this figure would have been of around $1 million. Although the exact amount of direct incentives per job place may vary, the table below clearly shows a stark difference in costs between Foxconn and Amazon projects.

Thus, it is not surprising that doubts aroused about the viability of the Foxconn project. The taxpayer burden carried by Amazon incentives were one of the main reasons behind a strong antagonism among the local residents. The tax burden, along with the surge of housing prices and the increasing pressure on the local transit system that would be triggered by the construction of the headquarters, ultimately led to a demise of Amazon plans.

The agreement hailed by Mr. Trump as his personal victory, however, has generated some turbulence, due to the outbreak of the global trade war, to the shifts in the US political climate and, finally, to a slowdown in the smartphone industry sales, from which Foxconn has been strongly impacted. After almost two years, Foxconn is yet to deliver the aforementioned capital and the workforce.

This leads to some doubts on the feasibility of Foxconn project, which seems to show some similarities with the Amazon case: indeed, the tech giant decided to change its plans to establish a headquarters in New York.

The skepticism about cost and benefit ratio of the Foxconn project emerged long before the trade war inception. A detailed study by the Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau concluded that the deal would not pass its breakeven point until at least the 2042-43 fiscal year, and even this forecast appeared as highly optimistic. The report overconfidently projected a significant magnitude of income tax inflows and failed in not recognize the additional expenditures associated with public services that would be inevitable for such a large-scale project.

In addition, the deal appeared extraordinary in terms of the average incentive per job place provided by the US government, which is notoriously severe in providing subsidies. According to Timothy Bartik, from the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Foxconn planned to receive an amount of subsidy per promised workplace several times larger than the one historically provided by the US government.

The exceptionality of the dimension of Foxconn subsidy is best demonstrated by the comparison against possible subsidization of Amazon. Amazon press release reported that Amazon would have received around $1.2 billion in refundable tax credit and a cash grant of $325 million over the following decade, in exchange for 25,000 workplaces to be generated in Long Island City, New York. In Arlington, Virginia, where the tech giant would have added another 25,000 jobs, it would have been provided a cash grant of $570 million. Similarly, another $100 million in cash grant for capital expenditures and job tax credit would have been offered over the following seven years in Nashville, Tennessee, for hiring 5,000 employees.

In general, the uncertainty of such projects makes the prediction of its costs a highly demanding task. Jeffrey Dorfman, from the University of Georgia, estimated that the Foxconn deal would have had cost of at least $230,000 per job for a local taxpayer, whereas Tim Culpan from Bloomberg claimed that this figure would have been of around $1 million. Although the exact amount of direct incentives per job place may vary, the table below clearly shows a stark difference in costs between Foxconn and Amazon projects.

Thus, it is not surprising that doubts aroused about the viability of the Foxconn project. The taxpayer burden carried by Amazon incentives were one of the main reasons behind a strong antagonism among the local residents. The tax burden, along with the surge of housing prices and the increasing pressure on the local transit system that would be triggered by the construction of the headquarters, ultimately led to a demise of Amazon plans.

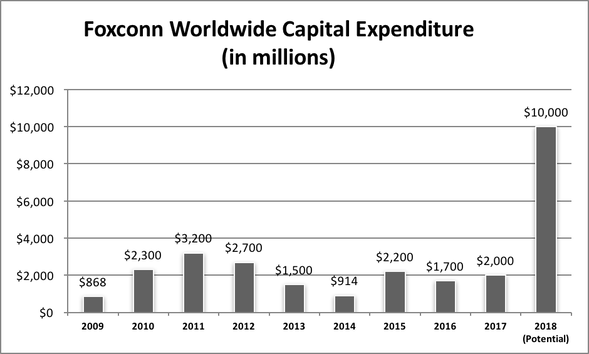

Similarly, one would be sensible in having a great deal of disbelieving in the credibility of a pledge to deliver $10 billion investments, even more so considering the environment of turmoil that currently surrounds Foxconn. The promised amount of $10 billion would be more than the total capital expenditure that Foxconn invested worldwide in the five years between 2013 and 2017.

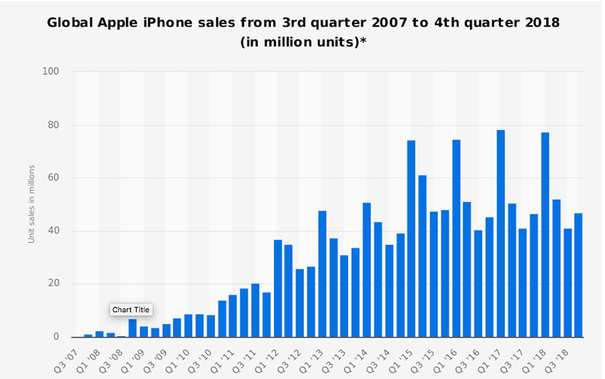

In addition, this pledge comes amidst of hawkish expense-cutting measures that include early layoffs of 100,000 seasonal workers ad organizational restructuring for Apple, which counts Foxconn as one its main manufacturers. Mainly driven by a slowdown in the economic growth in China and the trade disputes, weak demand for smartphones inflicted a heavy blow to Apple’s production plans.

Cupertino-based firm already announced that it would scale down the production orders of the newest iPhone models by around ten percent. This has been reflected in a further downward movement in Foxconn revenues . Foxconn has reported an eight percent decrease in December month revenues, its first sales decrease in ten months, and is preparing to have “a difficult 2019”, as its CEO, Terry Gou, warned. Thus, the current environment will not make it easy for Foxconn to fund the Wisconsin project.

Sultan Massalov

Sultan Massalov