After the success of our first event on activist short selling, BSCM Hedge Fund Series is back! We are glad to announce that on Tuesday 30th of March, Bocconi Students Capital Markets will host two exceptional investors and activists to talk about hedge fund activism in Europe: Gianluca Ferrari (Gianluca is a highly experienced investor who built its early career at Shareholder Value Management AG in Frankfurt, and recently co-funded Clearway Capital - an activist hedge fund focused on driving ESG change in companies) and Stefano Sardo (who is an investment professional currently partner at EMIP, a Milan-based consultant and advisor, providing services to Elliott Advisors (UK) Limited - Stefano has been directly involved in several Elliott's activist campaigns in Italy and abroad). Here is the link to register to the event (slots are limited!): tinyurl.com/HFActivism.

During the event, moderated by Professor Laura Zanetti, our guests will talk about the state of hedge fund activism in Europe with a completely practical approach, by bringing many insights from their incredible experience.

We felt the need to clear them the way and bring all attendees on the same level playing field. This article will tackle what you need to know about activism, including history, methods and tactics, performances, and current trends, while an in-depth analysis of a recent activist campaign will follow in the next few days.

During the event, moderated by Professor Laura Zanetti, our guests will talk about the state of hedge fund activism in Europe with a completely practical approach, by bringing many insights from their incredible experience.

We felt the need to clear them the way and bring all attendees on the same level playing field. This article will tackle what you need to know about activism, including history, methods and tactics, performances, and current trends, while an in-depth analysis of a recent activist campaign will follow in the next few days.

Introduction

Starting from the end of the 1900s, hedge fund activism has risen as a dominant corporate governance mechanism as well as a profitable investment strategy. This is just the latest example of a much broader phenomenon, known as “shareholder activism”, which dates back to the early 20th century. Its origins are rooted in the separation between ownership and control and, in particular, in the subsequent need for shareholders to monitor the work and performance of managers in order to ensure that their actions are always in shareholders’ best interests.

To give a definition, shareholder activism refers to a situation where a shareholder of a publicly traded company attempts to exploit his or her equity stake, and so his or her voting rights and influence, in order to arouse changes within or for the company. Gillan and Starks (2007) define active shareholders as “investors who, dissatisfied with some aspect of a company’s management or operations, try to bring about change within the company without a change in control”.

In that sense, hedge funds are certainly not the first example of activist shareholders. In the last century, individual investors first and then other institutional investors tried to play an active role in the monitoring process. However, the regulatory framework and structural barriers - such as free-rider problems and conflicts of interest (Brav, Jiang and Kim, 2010) - hindered mutual and pension funds’ role as activist shareholders. The empirical proof of the overall failure of such initiatives is that – in the several studies conducted with regards to this topic – positive abnormal returns rarely have been recorded.

Why should hedge funds be more successful in carrying out activist campaigns than other institutional investors? The reason is that hedge funds are characterized by a bundle of unique features that facilitate and encourage the pursuit of an active role in the management of targeted companies. The most remarkable characteristics are the possibility to operate with more freedom (with regards to both instruments and regulation) as well as stronger incentives to produce positive abnormal returns. As a proof to testify the importance and relevance of hedge fund activism nowadays, in the US the number of activist campaigns went from 34 in 2000 to 225 in 2019 (FactSet), but this trend can easily be extended to all developed countries.

To give a definition, shareholder activism refers to a situation where a shareholder of a publicly traded company attempts to exploit his or her equity stake, and so his or her voting rights and influence, in order to arouse changes within or for the company. Gillan and Starks (2007) define active shareholders as “investors who, dissatisfied with some aspect of a company’s management or operations, try to bring about change within the company without a change in control”.

In that sense, hedge funds are certainly not the first example of activist shareholders. In the last century, individual investors first and then other institutional investors tried to play an active role in the monitoring process. However, the regulatory framework and structural barriers - such as free-rider problems and conflicts of interest (Brav, Jiang and Kim, 2010) - hindered mutual and pension funds’ role as activist shareholders. The empirical proof of the overall failure of such initiatives is that – in the several studies conducted with regards to this topic – positive abnormal returns rarely have been recorded.

Why should hedge funds be more successful in carrying out activist campaigns than other institutional investors? The reason is that hedge funds are characterized by a bundle of unique features that facilitate and encourage the pursuit of an active role in the management of targeted companies. The most remarkable characteristics are the possibility to operate with more freedom (with regards to both instruments and regulation) as well as stronger incentives to produce positive abnormal returns. As a proof to testify the importance and relevance of hedge fund activism nowadays, in the US the number of activist campaigns went from 34 in 2000 to 225 in 2019 (FactSet), but this trend can easily be extended to all developed countries.

Hedge funds and the rise of hedge fund activism

Hedge funds are pooled, privately organized investment vehicles – not widely available to the public. They are run by professional managers and are subject to less regulation and requirements than other institutional investors (such as pension funds). Generally, hedge funds are structured as limited partnerships, open to a limited number of accredited investors (acting as limited partners – while the fund manager is the general partner) and requiring a large initial minimum investment.

While other institutional investors generally measure their performance against a benchmark, in most cases hedge funds’ objective is to produce absolute returns, i.e. a return that is ‘‘market neutral’’ (i.e. with low correlation to financial markets). The strategies employed by hedge funds to achieve their goals are numerous and in general we can identify the following: long-short, relative value, event driven, arbitrage (merger, convertible, or fixed-income), credit, global macro, short-only and quantitative. We do not want to focus our attention too much on the different investment strategies, but it is evident that only a limited number of hedge funds systematically engage in activist campaigns, and in particular only those interested in taking large positions with a quite long-time horizon (usually longer than 2 years).

As mentioned previously, hedge funds present several characteristics that facilitate activist campaigns compared to other “active” investors (such as pension funds or mutual funds). Firstly, hedge fund managers’ compensation scheme strengthens the incentives to generate positive returns. Indeed, only a minor portion of managers’ retribution is fixed (generally, 2% of AUM), while the juiciest part is related to a performance fee (unlike pension and mutual funds), that generally amounts to 20% of annual returns generated by the fund (absolute or above a certain threshold or versus a benchmark, depending on the fund). In addition, hedge fund managers have significant personal investments in the fund. Secondly, hedge funds are not subject to most restrictions in place for other institutional investors. These investment vehicles are allowed to operate using leverage and derivatives, and both tools are used to facilitate the purchase of voting rights, which are directly proportional to the probability of success of an activist campaign. Hedge funds are allowed to acquire large block holdings in individual companies, without the minimum diversification requirements that constrain other institutional investors’ operations (in particular, mutual funds’ preferential tax status is tied to the maintenance of high levels of diversification). Furthermore, fund managers usually require investors to commit to a lock-up period of two years or more as well as demand notice well in advance of any withdrawal, allowing hedge funds to carry out long activist campaigns, holding large illiquid blocks, and bear liquidity costs much smaller than those of mutual funds. Finally, hedge funds’ bargaining power with the company’s management is strengthened by the fact that, in case of poor management’s performance, the fund has the resources and capabilities to buyout the company.

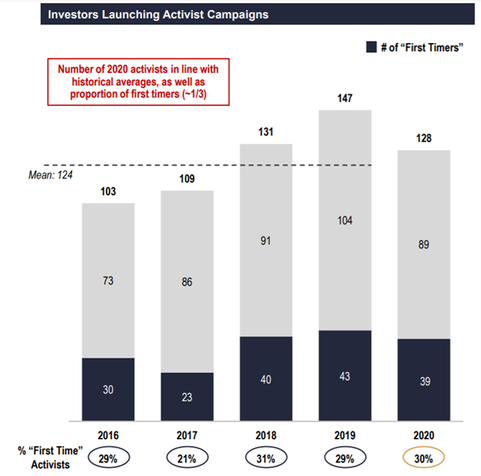

Given these characteristics, it is common for hedge funds to invest in companies without waiting for a catalyst event to occur in order to make the investment thesis work, while they actively engage with the company using a wide range of tactics (see next section) to unlock value. As a matter of fact, the players in the industry are a lot and expanding, and first-time activists continue to represent a big portion of new activity:

While other institutional investors generally measure their performance against a benchmark, in most cases hedge funds’ objective is to produce absolute returns, i.e. a return that is ‘‘market neutral’’ (i.e. with low correlation to financial markets). The strategies employed by hedge funds to achieve their goals are numerous and in general we can identify the following: long-short, relative value, event driven, arbitrage (merger, convertible, or fixed-income), credit, global macro, short-only and quantitative. We do not want to focus our attention too much on the different investment strategies, but it is evident that only a limited number of hedge funds systematically engage in activist campaigns, and in particular only those interested in taking large positions with a quite long-time horizon (usually longer than 2 years).

As mentioned previously, hedge funds present several characteristics that facilitate activist campaigns compared to other “active” investors (such as pension funds or mutual funds). Firstly, hedge fund managers’ compensation scheme strengthens the incentives to generate positive returns. Indeed, only a minor portion of managers’ retribution is fixed (generally, 2% of AUM), while the juiciest part is related to a performance fee (unlike pension and mutual funds), that generally amounts to 20% of annual returns generated by the fund (absolute or above a certain threshold or versus a benchmark, depending on the fund). In addition, hedge fund managers have significant personal investments in the fund. Secondly, hedge funds are not subject to most restrictions in place for other institutional investors. These investment vehicles are allowed to operate using leverage and derivatives, and both tools are used to facilitate the purchase of voting rights, which are directly proportional to the probability of success of an activist campaign. Hedge funds are allowed to acquire large block holdings in individual companies, without the minimum diversification requirements that constrain other institutional investors’ operations (in particular, mutual funds’ preferential tax status is tied to the maintenance of high levels of diversification). Furthermore, fund managers usually require investors to commit to a lock-up period of two years or more as well as demand notice well in advance of any withdrawal, allowing hedge funds to carry out long activist campaigns, holding large illiquid blocks, and bear liquidity costs much smaller than those of mutual funds. Finally, hedge funds’ bargaining power with the company’s management is strengthened by the fact that, in case of poor management’s performance, the fund has the resources and capabilities to buyout the company.

Given these characteristics, it is common for hedge funds to invest in companies without waiting for a catalyst event to occur in order to make the investment thesis work, while they actively engage with the company using a wide range of tactics (see next section) to unlock value. As a matter of fact, the players in the industry are a lot and expanding, and first-time activists continue to represent a big portion of new activity:

Source: 2020 Review of Shareholder Activism, Lazard’s Shareholders Advisory Group

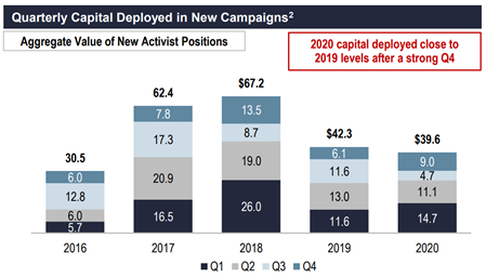

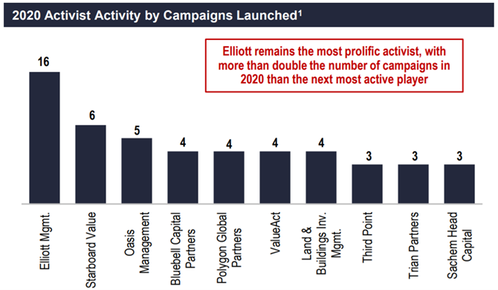

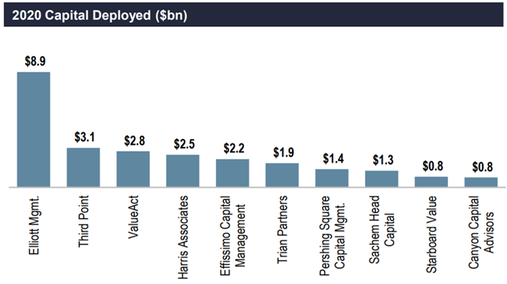

At the same time, the amount of global activists’ AUM is currently above $100bn (we lack reliable estimates), while the most important and active players in the sector are the following:

Source: 2020 Review of Shareholder Activism, Lazard’s Shareholders Advisory Group

Source: 2020 Review of Shareholder Activism, Lazard’s Shareholders Advisory Group

Source: 2020 Review of Shareholder Activism, Lazard’s Shareholders Advisory Group

Objectives and methods

Hedge fund activism sees its origins in the de-conglomeration trend started in the 80s, with investors acquiring big stakes in diversified companies to ask for breakups and divestitures, to increase the value of each standalone business and to return capital to shareholders. Probably the most prominent exponent and investor of this trend was Carl Icahn, who became famous after the hostile takeover of Trans World Airlines in 1985. However, from 1990s onwards the range of objectives and tools of activist hedge funds has widened, and the capital intensity of the activity has reduced (indeed, the average stake of activist hedge funds in target companies is now on average between 5% and 10%).

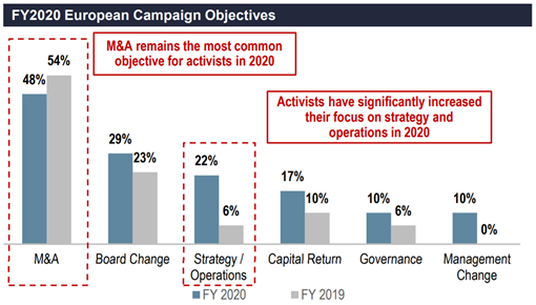

The goals of an activist campaign can usually be summarized in different categories, but we should underline the fact that campaigns are often a combination of various aspects. In particular, key objectives are:

Mergers & Acquisitions

M&A is usually one of the most common objectives in an activist campaign, with fund managers seeking to:

Strategy and operations

Hedge funds generally also push for strategic and operational changes, as they can often take an active collaborative role with the management of target companies to design new strategic objectives. These include operational changes to gain efficiency, potential acquisitions, new growth strategies or a wider business restructuring.

An example is the recent Elliott’s campaign in Public Storage (a U.S. REIT and operator of self-storage facilities), where the fund nominated two board directors to oversee a more aggressive growth strategy and catch up with industry peers’ growth.

Capital structure and capital return

This category includes all the campaigns aimed at increasing/decreasing leverage, increase dividends or buybacks, or other capital structure related issues. In this case, an interesting example is Michael Burry’s GameStop campaign (the famous Big Short investor and founder of Scion Asset Management) started in 2019, aimed at pushing GameStop to use its $500m of cash to buyback shares - considering that GameStop was capitalizing around $300m - in order to unlock value for shareholders. Then something unprecedented and partially unrelated to Micheal Burry’s campaign happened, and we all know the story. To know more about it here is a very complete article we wrote on GameStop a few weeks ago: www.bscapitalmarkets.com/deep-dig-into-january-reddit-rally-ndash-march-4-2021.html.

Board change, governance, and management change

Finally, campaigns may be aimed at pushing for a change in management (e.g. change of the CEO), increase board independence and fair representation, better governance practices, or increase information disclosure. These types of campaigns are very common and are gaining more and more ground in Europe where good governance practices are still less developed than in the US.

With regards to this topic Bluebell Capital - a London based hedge fund led by three Italians (Francesco Trapani, Giuseppe Bivona, and Marco Taricco) - is gaining a lot of momentum. Some of their recent campaigns include their push to change CEO and separate the CEO and Chairman role at Danone, the appointment of an external CEO at Mediobanca, or the more recent investment in UniCredit alongside their criticism against Pier Carlo Padoan (former Italian economic minister) as potential next president of the group who could raise in their opinion big governance issues.

The goals of an activist campaign can usually be summarized in different categories, but we should underline the fact that campaigns are often a combination of various aspects. In particular, key objectives are:

Mergers & Acquisitions

M&A is usually one of the most common objectives in an activist campaign, with fund managers seeking to:

- Sell the company or pursue a merger;

- Break-up the company or push the target to divest part of its non-core business lines;

- Scuttle or sweeten existing deals, and this is done by entering a live M&A situation in order to improve deal terms or block a negatively perceived transaction.

Strategy and operations

Hedge funds generally also push for strategic and operational changes, as they can often take an active collaborative role with the management of target companies to design new strategic objectives. These include operational changes to gain efficiency, potential acquisitions, new growth strategies or a wider business restructuring.

An example is the recent Elliott’s campaign in Public Storage (a U.S. REIT and operator of self-storage facilities), where the fund nominated two board directors to oversee a more aggressive growth strategy and catch up with industry peers’ growth.

Capital structure and capital return

This category includes all the campaigns aimed at increasing/decreasing leverage, increase dividends or buybacks, or other capital structure related issues. In this case, an interesting example is Michael Burry’s GameStop campaign (the famous Big Short investor and founder of Scion Asset Management) started in 2019, aimed at pushing GameStop to use its $500m of cash to buyback shares - considering that GameStop was capitalizing around $300m - in order to unlock value for shareholders. Then something unprecedented and partially unrelated to Micheal Burry’s campaign happened, and we all know the story. To know more about it here is a very complete article we wrote on GameStop a few weeks ago: www.bscapitalmarkets.com/deep-dig-into-january-reddit-rally-ndash-march-4-2021.html.

Board change, governance, and management change

Finally, campaigns may be aimed at pushing for a change in management (e.g. change of the CEO), increase board independence and fair representation, better governance practices, or increase information disclosure. These types of campaigns are very common and are gaining more and more ground in Europe where good governance practices are still less developed than in the US.

With regards to this topic Bluebell Capital - a London based hedge fund led by three Italians (Francesco Trapani, Giuseppe Bivona, and Marco Taricco) - is gaining a lot of momentum. Some of their recent campaigns include their push to change CEO and separate the CEO and Chairman role at Danone, the appointment of an external CEO at Mediobanca, or the more recent investment in UniCredit alongside their criticism against Pier Carlo Padoan (former Italian economic minister) as potential next president of the group who could raise in their opinion big governance issues.

Source: 2020 Review of Shareholder Activism, Lazard’s Shareholders Advisory Group

But how do hedge funds achieve these objectives?

Activist hedge funds posses a wide range of tools to engage with the target company and drive change. The first but also less recognized tool is certainly the hedge fund’s reputation in delivering value and its credibility based on its past campaigns. This factor goes always hand in hand with all the tactics adopted by hedge funds, that are mainly (Brav, Jiang, Partnoy, and Thomas, 2008) (tactics are listed from the least to the most hostile):

On the other hand, target companies’ management teams are not passive, and with the help of consultants, investment bankers and lawyers, they often design a response strategy in order to manage the campaign, with the aim of maintaining their credibility and maintaining a unified consensus on the Board of Directors.

Activist hedge funds posses a wide range of tools to engage with the target company and drive change. The first but also less recognized tool is certainly the hedge fund’s reputation in delivering value and its credibility based on its past campaigns. This factor goes always hand in hand with all the tactics adopted by hedge funds, that are mainly (Brav, Jiang, Partnoy, and Thomas, 2008) (tactics are listed from the least to the most hostile):

- Engage and communicate with the board and the management on a regular basis in order to enhance shareholder value. This is a quite common strategy, and is also intuitively the less hostile one, but can deliver great successes without the risks posed by a more hostile approach. However, it requires management collaboration and is not always easy to obtain.

- The hedge fund wants board representation but without a proxy contest.

- The investor makes a formal shareholder proposal. This is also known as shareholder resolution, i.e. proposals voted at the company’s annual meeting – which frequently attract significant attention from the public.

- Publicity campaigns (i.e. using mass media to draw the public’s attention to a problem or issue in a corporation and put pressure on the management and gain support from other shareholders).

- The hedge fund can launch a proxy contest to gain board seats, thus trying to replace the board (partially or totally). This is one of the most hostile tactics a hedge fund can undertake, as in practice the board is usually proposed by the management and then approved by shareholders. In a proxy contest, hedge funds present alternative candidates (against the management proposal) and seeks support from other shareholders in order to win the vote and have representation in the BoD of the company.

- Hedge funds can also sue the company (however, this is usually expensive and non-constructive).

- Finally, hedge funds can always threaten to takeover the company or eventually do it (although this is rare).

On the other hand, target companies’ management teams are not passive, and with the help of consultants, investment bankers and lawyers, they often design a response strategy in order to manage the campaign, with the aim of maintaining their credibility and maintaining a unified consensus on the Board of Directors.

Activist Hedge Funds Performance

However, does the use of these tactics really enable hedge funds to create value for their (general) partners?

An important task when assessing the viability of any investment is to analyse the returns it is able to generate and its past performance. Below we will analyse the performance of activist hedge funds in two ways: first we look at what happens around the time of announcement of an activist intervention, then we look at the monthly and yearly returns of activist hedge funds with respect to all hedge funds.

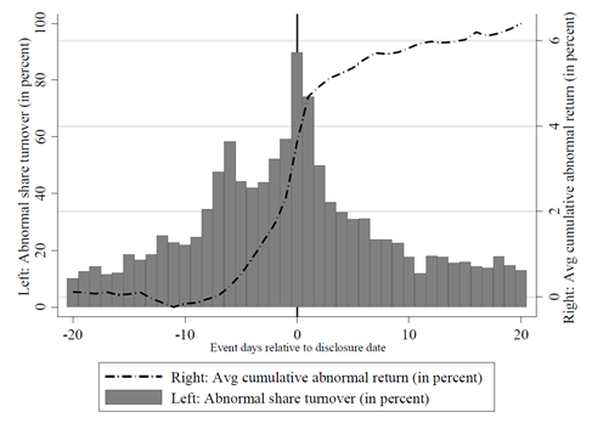

The most comprehensive analysis of the stock price behaviour of activism targets has been carried out by Becht et al. (2017). The authors analyse a sample of 1740 activist interventions (by 330 funds) in 23 countries, for the time period 2000-2010.

The authors find significant abnormal returns of around 7% with respect to local market exposure in a window of (-20, +20) days around the announcement of the activist stake in the target. Furthermore, they also find significant excess turnover in the same time window.

An important task when assessing the viability of any investment is to analyse the returns it is able to generate and its past performance. Below we will analyse the performance of activist hedge funds in two ways: first we look at what happens around the time of announcement of an activist intervention, then we look at the monthly and yearly returns of activist hedge funds with respect to all hedge funds.

The most comprehensive analysis of the stock price behaviour of activism targets has been carried out by Becht et al. (2017). The authors analyse a sample of 1740 activist interventions (by 330 funds) in 23 countries, for the time period 2000-2010.

The authors find significant abnormal returns of around 7% with respect to local market exposure in a window of (-20, +20) days around the announcement of the activist stake in the target. Furthermore, they also find significant excess turnover in the same time window.

Source: Becht et al. (2017)

The probability of an engagement being successful, having therefore at least one outcome (e.g., restructuring, board changes, changes in pay-out policy and takeovers) is 53% of the sample analysed, with large variability across geographies (61% in North America, 50% in Europe but only 18% in Asia). Furthermore, engagements that lead to multiple outcomes tend to have a stronger positive impact than those that lead to one or none. This is particularly noticeable in engagements concerning multiple outcomes including a takeover, in which the abnormal return is on average 18.1% in the analysed time window.

The authors also find that stock performance is higher when wolf packs form, that is, multiple activists participate in the same deal. This comes from a higher probability of success in the engagement, and not from higher returns in successful engagements. There is an open debate on whether this happens because activists join forces or just because they find themselves pursuing the same target without coordination, thus happening just because the target is a good one and easy to spot.

Among other things, the authors also find out that activism tends to generate higher returns when target firms are larger, have strong institutional ownership (especially if from US institutional investors), and that domestic activism campaigns tend to have higher returns than foreign ones.

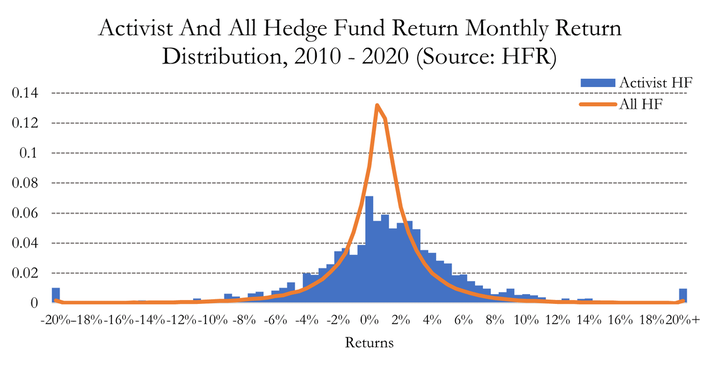

In order to provide a comprehensive review of the performance of activist hedge funds also in the past ten years, we have collected data from HFR, one of the world’s largest data providers for hedge funds (beware that this service does not collect data from all hedge funds). The sample selected includes the monthly returns from January 2010 to October 2020 for all hedge funds still alive by the latter date. Be therefore aware that this sample does not include hedge funds that have been closed down during this period. The total number of observations amounts to 2,866 for activist hedge funds and 310,142 for all hedge funds.

The monthly returns distributions are visibly different for the two samples. While both are not normally distributed (having a taller head and fatter tails than a normal distribution), there is a noticeably higher concentration of observations around the mean for the comprehensive sample with respect to the activist sample. We can therefore see that activist hedge funds returns are more dispersed, have a higher variance with respect to other hedge funds, and are more likely to have extreme performances (as it can be seen from the higher relative frequency in the -20%- and 20%+ buckets). The mean monthly return for activist hedge funds in the sample is 0.91% with a standard deviation of 7.54%, while for all hedge funds these two statistics are 0.44% and 3.82% respectively. The interquartile range for activists is (-1.69%, 3.31%) and for all hedge funds (-0.74%, 1.69%).

The authors also find that stock performance is higher when wolf packs form, that is, multiple activists participate in the same deal. This comes from a higher probability of success in the engagement, and not from higher returns in successful engagements. There is an open debate on whether this happens because activists join forces or just because they find themselves pursuing the same target without coordination, thus happening just because the target is a good one and easy to spot.

Among other things, the authors also find out that activism tends to generate higher returns when target firms are larger, have strong institutional ownership (especially if from US institutional investors), and that domestic activism campaigns tend to have higher returns than foreign ones.

In order to provide a comprehensive review of the performance of activist hedge funds also in the past ten years, we have collected data from HFR, one of the world’s largest data providers for hedge funds (beware that this service does not collect data from all hedge funds). The sample selected includes the monthly returns from January 2010 to October 2020 for all hedge funds still alive by the latter date. Be therefore aware that this sample does not include hedge funds that have been closed down during this period. The total number of observations amounts to 2,866 for activist hedge funds and 310,142 for all hedge funds.

The monthly returns distributions are visibly different for the two samples. While both are not normally distributed (having a taller head and fatter tails than a normal distribution), there is a noticeably higher concentration of observations around the mean for the comprehensive sample with respect to the activist sample. We can therefore see that activist hedge funds returns are more dispersed, have a higher variance with respect to other hedge funds, and are more likely to have extreme performances (as it can be seen from the higher relative frequency in the -20%- and 20%+ buckets). The mean monthly return for activist hedge funds in the sample is 0.91% with a standard deviation of 7.54%, while for all hedge funds these two statistics are 0.44% and 3.82% respectively. The interquartile range for activists is (-1.69%, 3.31%) and for all hedge funds (-0.74%, 1.69%).

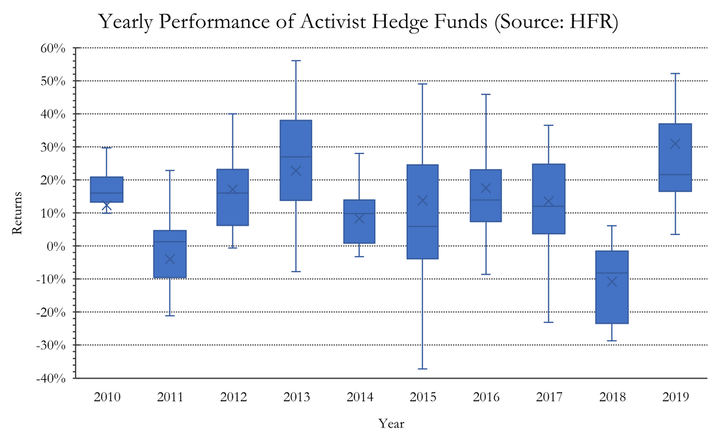

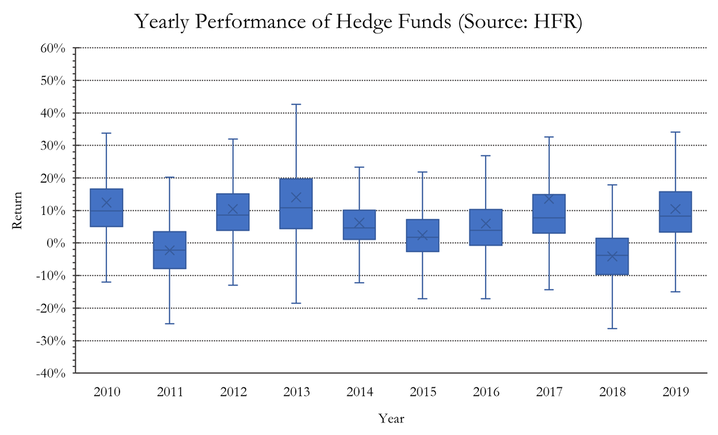

The trends are similar when comparing the distribution of annual (calendar year) returns for the two samples. While over the years the two statistics seem to follow a similar up and down pattern, the activist funds have a larger interquartile range than other hedge funds. These plots also put emphasis on how variable the performance is across funds, and how investing in a good or bad performer can lead to really large return differences. In fact, investing in a top-quartile instead of a bottom-quartile activist fund in 2019 would have resulted in a difference of at least 20% in returns!

For what pertains 2020, although the activity was initially slowed down by the pandemic, many illustrious funds ended up racking really high returns. Among these we find Pershing Square Capital Holdings whose publicly traded shares rose 70.2%, Welling’s Engaged Capital returning 51% and Citron Research returning 155%. This last fund has however been in the eye of the storm in 2021 (together with Melvin Capital and others), as it has been one of the most renowned targets of a short squeeze organized by retail investors on stocks like GameStop and AMC Entertainment in early 2021.

Finally, some critics against activist hedge funds performances state that their investment horizon is short and so they push changes in companies aiming at short term benefits (as cutting costs, increase dividends, and others), but by leading to an underperformance in the long run. However, there is mixed evidence of this in the data to support the argument and we feel that a case-by-case analysis would be more appropriate.

Finally, some critics against activist hedge funds performances state that their investment horizon is short and so they push changes in companies aiming at short term benefits (as cutting costs, increase dividends, and others), but by leading to an underperformance in the long run. However, there is mixed evidence of this in the data to support the argument and we feel that a case-by-case analysis would be more appropriate.

Trends

Secondly to returns, activism is not a static world and hedge fund managers move each time in many different directions to seek opportunities and returns – and these days are not an exception. Indeed, in what follows we analyse the major trends for activism and activist hedge funds for the upcoming years.

SPACs and activism

Activist hedge funds have been jumping on one of the hottest trends of the last years in capital markets. In May 2020, Hudson Executive Capital launched a SPAC to acquire a target in the fintech space. Pershing Square held an IPO raising $4 Bn for a SPAC targeting mature, established firms with billion-dollar valuation. In the prospectus the fund pointed out that their vehicle would be a good investment as they would be able to “finalize the principal terms of a transaction with a merger partner prior to their public disclosure” and this would make the SPAC more attractive than a traditional IPO. This deal has been under intense scrutiny from the investing world, and many are trying to predict which firm will be targeted by Bill Ackman.

ESG focus

The increase in attention given to ESG practices by asset managers has been one of the strongest trends in the industry and will likely remain so for many years (we will also talk about this during the event). The emergence of unified sustainability reporting standards is one of the key events that could make the world shift to a greener future, and activist investors will be on the forefront of their adoption.

In this trend, activists usually seek to invest in bad companies from an ESG perspective and push them to make real changes. This does not only benefit our environment and society, but also unlocks the ESG premium and allows the Fund to make money (indeed, companies that score good from an ESG perspective trade on average at premium, for many reasons including the fact that an increasing number of funds can only invest in high ESG rated companies). An example of this is Engine No.1’s push to shift ExxonMobil towards sustainable value creation.

Private Equity turning towards activism in public markets

Private equity firms are increasing their activities in public markets, including the employment of activist’s tools. Some of these investors have had long lasting involvements in public markets (like TPG and Ares Management), while others have just recently started to engage more in them through investments like PIPEs. 2020 has seen a substantial amount of private equity activism, including KKR filing a 13D form at Dave & Busters to receive board representation, Cerberus requesting changes at Commerzbank (including having representation in the board) and Oaktree disclosing two public active investments. The participation of private equity funds in activist campaigns could potentially lead to better return for hedge funds through the previously analysed wolf pack effect.

At the same time, the opposite is also happening, i.e. hedge funds making private equity style investments. An example is the recent expansion of Elliott in the PE world, as its recent bid to bring Cubic Corp. (a defense and transportation company) private testify.

End of the liquidity premium

During the pandemic firms with high liquidity have obtained higher returns due to their resilience to adversity. As happened after the Great Financial Crisis, with the end of adversities activist hedge funds will have the possibility to target firms with excess levels of liquidity, no longer priced by the market, to request pay-outs to shareholders. This could mark the beginning of the “recovery era”. There already are different examples of this trend, including the campaign of Elliot Management to have Crown Castle change its capital allocation and increase its dividends in the second half of 2020. Furthermore, there have been signs of companies with ongoing activist participation (like Comcast) starting to ramp up their pay-outs.

Retail Investors

One other interesting question going forward will be whether there are going to be further clashes between activist hedge funds and retail investors in the future. The events of the first months of 2021 and the “Reddit frenzy” are definitely to be accounted for, especially by activist short sellers. It is likely that the frequency of these events will decrease after the end of the pandemic, when the US government will stop giving out stimulus checks, which are an important source of cash to invest for the newest retail investors that are coordinating on social media.

Overall, the role of activism and activist hedge funds in capital markets has been gaining more and more importance over the years, and it is one of the hottest trends in the financial world.

SPACs and activism

Activist hedge funds have been jumping on one of the hottest trends of the last years in capital markets. In May 2020, Hudson Executive Capital launched a SPAC to acquire a target in the fintech space. Pershing Square held an IPO raising $4 Bn for a SPAC targeting mature, established firms with billion-dollar valuation. In the prospectus the fund pointed out that their vehicle would be a good investment as they would be able to “finalize the principal terms of a transaction with a merger partner prior to their public disclosure” and this would make the SPAC more attractive than a traditional IPO. This deal has been under intense scrutiny from the investing world, and many are trying to predict which firm will be targeted by Bill Ackman.

ESG focus

The increase in attention given to ESG practices by asset managers has been one of the strongest trends in the industry and will likely remain so for many years (we will also talk about this during the event). The emergence of unified sustainability reporting standards is one of the key events that could make the world shift to a greener future, and activist investors will be on the forefront of their adoption.

In this trend, activists usually seek to invest in bad companies from an ESG perspective and push them to make real changes. This does not only benefit our environment and society, but also unlocks the ESG premium and allows the Fund to make money (indeed, companies that score good from an ESG perspective trade on average at premium, for many reasons including the fact that an increasing number of funds can only invest in high ESG rated companies). An example of this is Engine No.1’s push to shift ExxonMobil towards sustainable value creation.

Private Equity turning towards activism in public markets

Private equity firms are increasing their activities in public markets, including the employment of activist’s tools. Some of these investors have had long lasting involvements in public markets (like TPG and Ares Management), while others have just recently started to engage more in them through investments like PIPEs. 2020 has seen a substantial amount of private equity activism, including KKR filing a 13D form at Dave & Busters to receive board representation, Cerberus requesting changes at Commerzbank (including having representation in the board) and Oaktree disclosing two public active investments. The participation of private equity funds in activist campaigns could potentially lead to better return for hedge funds through the previously analysed wolf pack effect.

At the same time, the opposite is also happening, i.e. hedge funds making private equity style investments. An example is the recent expansion of Elliott in the PE world, as its recent bid to bring Cubic Corp. (a defense and transportation company) private testify.

End of the liquidity premium

During the pandemic firms with high liquidity have obtained higher returns due to their resilience to adversity. As happened after the Great Financial Crisis, with the end of adversities activist hedge funds will have the possibility to target firms with excess levels of liquidity, no longer priced by the market, to request pay-outs to shareholders. This could mark the beginning of the “recovery era”. There already are different examples of this trend, including the campaign of Elliot Management to have Crown Castle change its capital allocation and increase its dividends in the second half of 2020. Furthermore, there have been signs of companies with ongoing activist participation (like Comcast) starting to ramp up their pay-outs.

Retail Investors

One other interesting question going forward will be whether there are going to be further clashes between activist hedge funds and retail investors in the future. The events of the first months of 2021 and the “Reddit frenzy” are definitely to be accounted for, especially by activist short sellers. It is likely that the frequency of these events will decrease after the end of the pandemic, when the US government will stop giving out stimulus checks, which are an important source of cash to invest for the newest retail investors that are coordinating on social media.

Overall, the role of activism and activist hedge funds in capital markets has been gaining more and more importance over the years, and it is one of the hottest trends in the financial world.

Conclusion

To conclude, the rise of activist hedge funds in the last two decades is a clear sign of their importance for companies and our economy. Moreover, they play a crucial rule in nowadays financial markets dominated by passive funds, by working hard on closing the gap between prices and fair value.

We strongly hope our analysis interested you and please – if you want to know more about how this world works with a strongly practical approach – join us on Tuesday 30th of March at 6.30pm on Teams (subscribe on Eventbrite at tinyurl.com/HFActivism).

See you there!

We strongly hope our analysis interested you and please – if you want to know more about how this world works with a strongly practical approach – join us on Tuesday 30th of March at 6.30pm on Teams (subscribe on Eventbrite at tinyurl.com/HFActivism).

See you there!

Lorenzo Gimigliano

Pietro Maraldi

Tommaso Pirozzi

Pietro Maraldi

Tommaso Pirozzi

BSCM would like to thank FactSet for giving us access to their platform and providing charts and data.

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

References

- FactSet

- HFR

- Becht M., Franks J,, Grant J., Wagner H., “Returns to Hedge Fund Activism: An International Study“, The Review of Financial Studies, 2017.

- Lazard, “2020 Review of Shareholder Activism”, 2021

- Jiang, Wei and Kim, Hyunseob and Brav, Alon, Hedge Fund Activism: A Review (2010). Foundations and Trends in Finance, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 1-66, February 2010.

- Gillan, Stuart L. and Starks, Laura T., The Evolution of Shareholder Activism in the United States (2007).

- https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-hedgefunds-activist/prominent-activist-investors-post-record-2020-returns-despite-pandemic-muted-activity-idUKKBN29B2XZ

- Pershing Square SPAC Prospectus, June 2020

- https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b1qsznm6l5604c/Reddit-Is-Convinced-It-Knows-Bill-Ackman-s-SPAC-Target-Ackman-Is-Paying-Attention

- https://www.ft.com/content/0f8b26e3-5e0e-4a89-9864-bb7186cf26fc